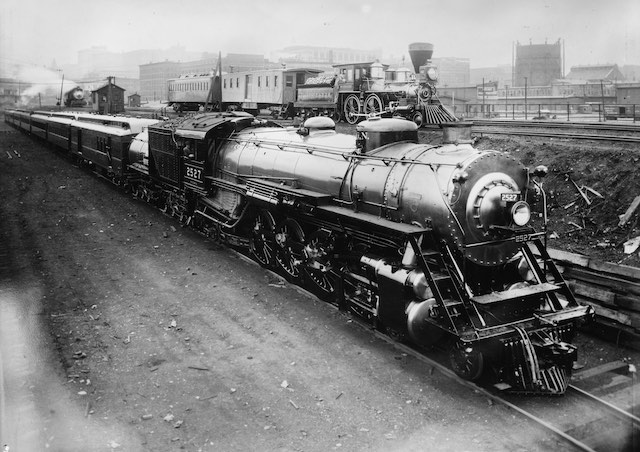

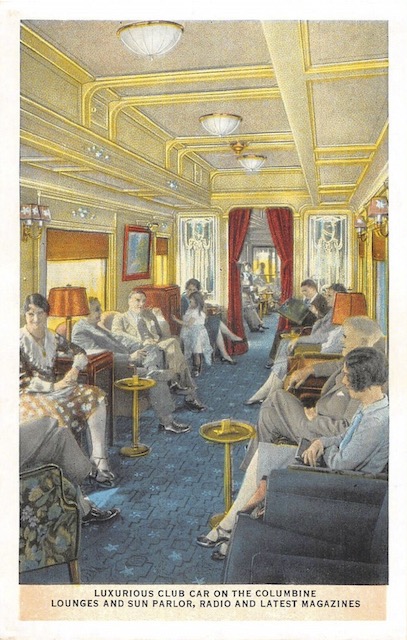

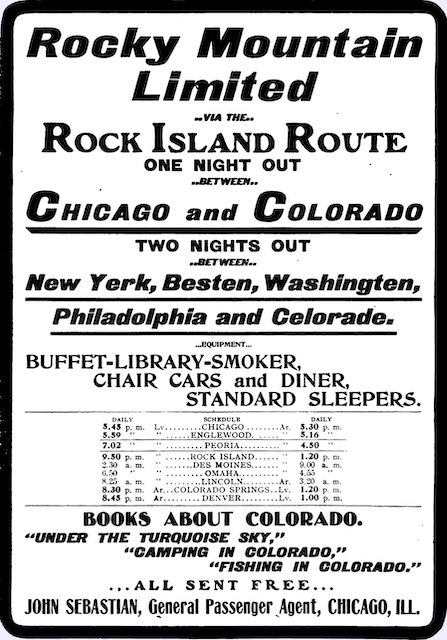

“The handsomest train ever seen in Denver steamed out of the Union Depot at 1:40 o’clock yesterday afternoon and disappeared down the tracks toward the east,” reported the Denver Post on May 4, 1899. “It was the first of a new service inaugurated today by the Burlington and will be known on the time cards as the Chicago Special.” According to the Post, the train consisted of five cars: a Pullman sleeper, two coaches, a baggage car, and a “composite” car that included a library and buffet.

This colorized photograph by William Henry Jackson is supposed to be of the Burlington Route’s Chicago Special. The train looks similar to the one described in the Post article with the addition of one more car, possibly a diner. The locomotive is a 2-6-0, which is an unusual choice for a passenger train. Built in 1899, the loco had 64″ drivers and almost 25,000 pounds of tractive effort. This must have been enough for Burlington’s train #6, which in 1899 took 29 hours and 35 minutes from Denver to Chicago, averaging 35 mph. Click image for a larger view of this photo from the Library of Congress.

The Post didn’t say so, but according to the Official Guide the train also included a diner. The Official Guide says the train started operating in April and doesn’t refer to the name Chicago Special or any other name. In fact, the train, which was designated #6, had been operating on the same schedule for about a year, and the only thing really new in April 1899 was the library-buffet car. Nevertheless, I am sure Burlington appreciated the publicity as the Chicago-Denver route was the railroad’s longest and one of its most heavily contested routes. Continue reading →

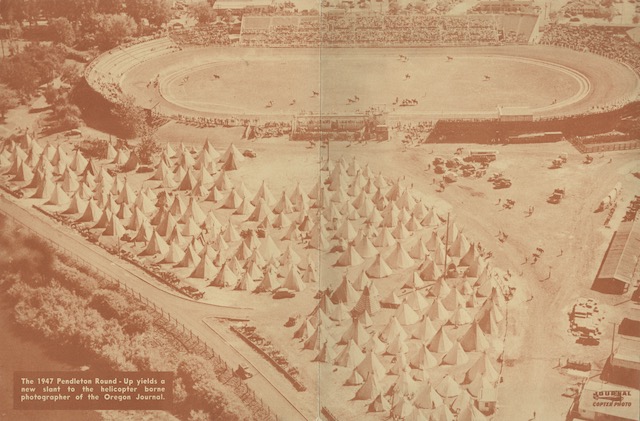

Click image to download a 29.3-MB PDF of this 48-page booklet from the Touchton Map Library, Tampa Bay History Center.

Click image to download a 29.3-MB PDF of this 48-page booklet from the Touchton Map Library, Tampa Bay History Center.