As the 20th century opened, Burlington’s train #1 was a stiff competitor, offering speed and comfort, if not exclusivity, in the Chicago-Denver corridor. One thing it didn’t have was an evocative name. Despite the Denver Post and William Henry Jackson calling train #6 the “Chicago Special,” neither the official guides nor Burlington’s own timetables nor any Burlington advertising I’ve been able to find used that or any other name for its any of its Chicago-Denver trains until late 1909.

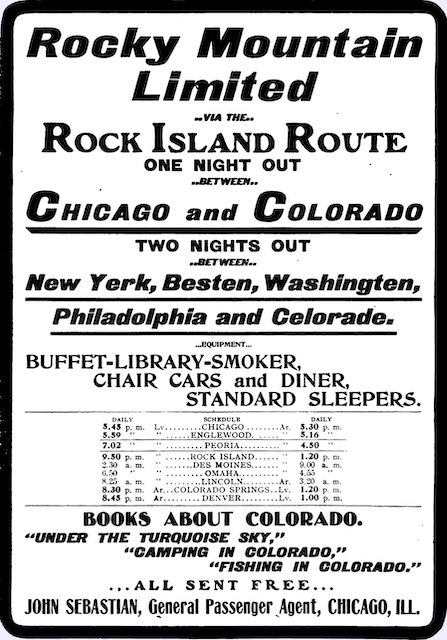

Unfortunately, the impact of this ad in the July, 1902 Official Guide was somewhat offset by the many times the typesetter confused “e” and “o.” Click image for a larger view.

Unfortunately, the impact of this ad in the July, 1902 Official Guide was somewhat offset by the many times the typesetter confused “e” and “o.” Click image for a larger view.

When Burlington finally did start naming its Denver trains in its timetables, the names weren’t very original: westbound train #1 became the Denver Limited, train #9 was the Colorado Limited, and #3 was the Overland Express, all of which were similar to names already used by Union Pacific. Eastbound, train #10 (counterpart to #1) was the Atlantic Coast Limited; train #6 (counterpart to #9) was the Chicago Limited (an upgrade from Chicago Special); and train #2 was the Overland Express. Again, these names weren’t very original. Wikipedia says at least a dozen railroads had a train called the Chicago Limited, and Burlington itself had at least three, with the other two heading to Chicago from Minneapolis and Kansas City.

Given that it had the slowest trains in the corridor, it made sense for the Rock Island to be the first to apply an evocative name to its premiere Chicago-Denver train: the Rocky Mountain Limited. By “evocative” I mean that the name quickly conveys a sense of romance and excitement about where the train is going. That can be due to geography, as in this case, or to the era, as in the case of the 20th Century Limited, or to technology, as any train named “Zephyr” immediately conveyed a sense of a high-speed silver streak with bright, modern interiors.

Trains with destination-oriented names, such as “Denver Special” or “Pacific Limited,” often used different names (“Chicago Special” or “Atlantic Limited”) going in the other direction, while evocative names for the most part did not. Rock Island initially broke this rule, for when it introduced the Rocky Mountain Limited in July, 1901, it named the train going in the other direction the Pan-American Limited. However, it quickly rectified this violation of a rule I just made up and by 1902 the train was called Rocky Mountain Limited in both directions.

Click image for a larger view.

Click image for a larger view.

Along with the new name, Rock Island speeded up the train to 28-3/4 hours westbound and slightly faster eastbound. It was still a little behind Burlington and UP, whose fastest trains in the corridor took 27-1/2 hours, but the difference was far less noticeable than before. As previously noted, however, Rock Island could get passengers to Colorado Springs faster than any other railroad.

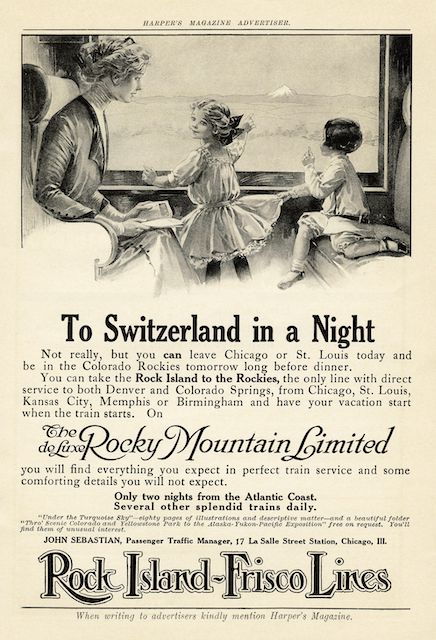

Drawing by Rose O’Neill. Click image for a larger view.

Drawing by Rose O’Neill. Click image for a larger view.

Rock Island took advantage of its evocative name in an intense publicity campaign emphasizing Colorado’s turquoise skies and outdoor opportunities. Some of its ads included drawings by Rose O’Neill, who was America’s most famous female illustrator and designer of the Kewpie doll.

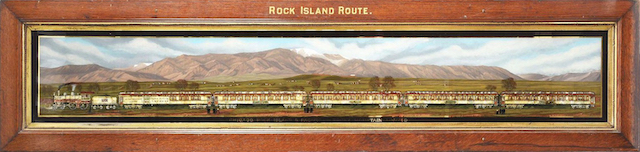

One curious bit of publicity resulted when one of Rock Island’s craftsman who help build wooden passenger cars also developed a hobby of making paintings incorporating mother of pearl. Rock Island hired him to paint the Rocky Mountain Limited. At least 15 of these paintings were made by Rock Island craftsmen, all a little different from one another. Most were hung in major Rock Island train stations or given to important customers. Perhaps half survive today.

Click image for a larger view.

Click image for a larger view.

The painting above shows Rock Island 4-4-0 1101 (an 1898 model built in Rock Island’s own shops with 78″ drivers and 20,470 pounds of tractive effort), but other mother of pearl paintings show different locomotives including a 4-4-2 Atlantic. The cars in the above painting include an express/buffet car, a chair car, two sleepers, and a diner, which is not too different from the 1899 Burlington train described in the Denver Post, not to mention earlier trains such as the Empire State Express of 1893. The landscape in the background of the pictures suggests that they show the Colorado Springs section of the Rocky Mountain Limited and that the full train west of Limon was longer.

Click image for a much larger view.

Click image for a much larger view.

The mother of pearl paintings are based on a series of photos taken by William Henry Jackson that could be assembled into a panorama. The photos show the smoker-library-buffet car, two sleeping cars named Westlake and Manila, a diner, and two chair cars following locomotive 1112 instead of 1101 (both of which were built to identical specifications). Either the last photo of the series is missing or Jackson didn’t take one, but another photo he took of the same train shows that the second chair car was the last car on the train.

It is uncertain where Jackson took these photos. However, there are no passengers in either the sleeping cars or the chair cars, so it seems likely the photos were taken in either Denver or Colorado Springs.

Instead of adapting evocative names, Burlington’s first response to the Rocky Mountain Limited was to start a rate war. In the same official guide in which Rock Island introduced its limited, Burlington announced round trip fares from Chicago to Denver as low as $25, which it claimed was “less than half fare.” While I suspect that’s an exaggeration, it did put Rock Island (not to mention UP) on notice that the competition would continue.