“The handsomest train ever seen in Denver steamed out of the Union Depot at 1:40 o’clock yesterday afternoon and disappeared down the tracks toward the east,” reported the Denver Post on May 4, 1899. “It was the first of a new service inaugurated today by the Burlington and will be known on the time cards as the Chicago Special.” According to the Post, the train consisted of five cars: a Pullman sleeper, two coaches, a baggage car, and a “composite” car that included a library and buffet.

This colorized photograph by William Henry Jackson is supposed to be of the Burlington Route’s Chicago Special. The train looks similar to the one described in the Post article with the addition of one more car, possibly a diner. The locomotive is a 2-6-0, which is an unusual choice for a passenger train. Built in 1899, the loco had 64″ drivers and almost 25,000 pounds of tractive effort. This must have been enough for Burlington’s train #6, which in 1899 took 29 hours and 35 minutes from Denver to Chicago, averaging 35 mph. Click image for a larger view of this photo from the Library of Congress.

The Post didn’t say so, but according to the Official Guide the train also included a diner. The Official Guide says the train started operating in April and doesn’t refer to the name Chicago Special or any other name. In fact, the train, which was designated #6, had been operating on the same schedule for about a year, and the only thing really new in April 1899 was the library-buffet car. Nevertheless, I am sure Burlington appreciated the publicity as the Chicago-Denver route was the railroad’s longest and one of its most heavily contested routes.

Denver was a town of around 4,000 people when the Union Pacific by-passed it during construction of the first transcontinental railroad. Denver business leaders raised funds to build a line to Cheyenne known as the Denver Pacific and finished it just two months before the Kansas Pacific completed its line from Kansas City to Denver. Between these rail connections and Denver’s proximity to Colorado mining districts the city rapidly grew and by 1880 was the second-largest city in the West after San Francisco. It remained in that position — bigger than Los Angeles, Portland, or Seattle — until after 1900, making it the target of several railroad lines.

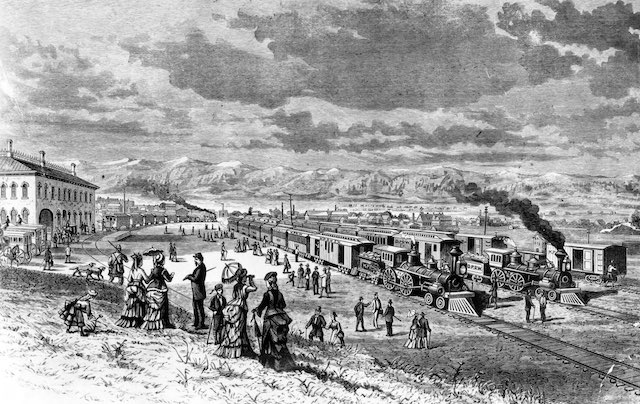

Denver’s train station in the 1870s with Denver & Rio Grande narrow-gauge tracks on the left, Kansas Pacific in the middle, and Denver Pacific on the right. Today’s Union Station is a couple of blocks on the other side of the station in this picture. Click image for a larger view.

Union Pacific took over the Denver Pacific and Kansas Pacific in 1880, but didn’t immediately start passenger service from Chicago to Denver that didn’t require at least one change of trains. That had to wait until 1882, when the Burlington reached Denver and began running something it briefly called the Denver and Pacific Express, which took 45-1/3 hours to get from Chicago to Denver. UP responded by claiming it had “the Omaha and Denver Short Line” and running a Chicago-Denver train (via Chicago & North Western) that took 47-3/4 hours.

In fact, the Burlington line was a few miles shorter. Instead of focusing on that, however, Burlington’s pages in the October 1882 Official Guide offered a long-winded preview of what would become Santa Fe’s main advertising slogan, stating that it “is specially a Denver line, as it is the only company operating its own line from Chicago, Peoria & St. Louis, both by way of Kansas City, by way of Pacific Junction, and by way of Omaha, through to Denver direct.” In short, take Burlington all the way.

In later years, Union Pacific and its partners would cooperate well with one another, but not in the late 19th century. At least through 1911, they couldn’t even agree on the names of all the joint trains they ran: in 1890, for example, C&NW called its Chicago-Denver trains the Denver Limited and Pacific Limited while UP called them the Denver Express and Pacific Express.

UP used the term “express” with good reason. In 1890, Burlington’s train #1 was a true limited, stopping just 8 times between the Missouri River and Denver (in fact, it didn’t even stop in Omaha), allowing it to make the Chicago-Denver trip in just 30-1/2 hours. UP’s fastest train, the Denver Express, stopped 24 times between the river and Denver, pushing its Chicago-Denver time to 38 hours and 35 minutes.

By 1890, the corridor had been joined by a new competitor: the Rock Island, which ran its Chicago-Denver trains via Kansas City. This route was 100 miles longer than either the UP or Burlington routes, but the Rock managed to schedule one train in just 38-1/4 hours for an average speed of 30 mph. This made it competitive with the UP-C&NW but not the Burlington.

The Rock Island’s disadvantage would be reduced in 1891, when it completed a line from Omaha to Beatrice, Nebraska, thus shortening its Chicago-Denver route from 1,161 to 1,093 miles. That was still longer than either UP’s (1,061) or Burlington’s (1,046 miles), but it made it much easier to compete, with one train that started in November 1891 taking just 34-2/3 hours from Chicago to Denver. Burlington responded by cutting 15 minutes from its already shorter time but UP lackadaisically added 5 minutes to its no longer competitive time.

The Rock Island had one thing that neither the Burlington nor the UP could provide: a direct line to Colorado Springs, with Denver and Colorado Springs sections splitting at Limon, Colorado. From Colorado Springs, passengers could take the Colorado Midland to Leadville, Glenwood Springs, and Grand Junction, and from there they could take the Rio Grande Western to Salt Lake City, options not provided by railroads out of Denver. Even if Rock Island’s trains were slower to Denver, they were faster to Colorado Springs than taking the UP or Burlington to Denver and then the Denver & Rio Grande to Colorado Springs.

A fourth competitor also joined the race in 1891: the Santa Fe, whose line to La Junta, Colorado connected with the joint Rio Grande-Santa Fe line to Denver. Santa Fe’s through train between Chicago and Denver was initially called the Denver & Utah Limited, and later the Colorado & Utah Limited, Denver Limited, and Colorado Express, but always numbered 5 & 6.

“Utah” figured into the early names because Santa Fe once owned the Colorado Midland and so could provide through cars over its own rails from Chicago to Grand Junction continuing to Ogden on the Rio Grande Western. However, Santa Fe lost control of the Midland in 1897 and so dropped “Utah” from the train names.

At 1,210 miles — later trimmed down to 1,174 miles — Santa Fe’s route was much longer than the others and was never very competitive on time. In 1891, #5 took about 42 hours from Chicago to Denver, 11-1/2 more than the Burlington’s fastest train.

Meanwhile, Burlington had something neither Santa Fe nor UP had: solvency. Hampered by its 1893 bankruptcy, Union Pacific was not able to match Burlington’s speeds until March 1898, when it reduced the time of the Colorado Special to 28-1/2 hours. The 1899 improvements in Burlington’s service reported by the Denver Post may have been specifically made in response to Union Pacific’s competition.

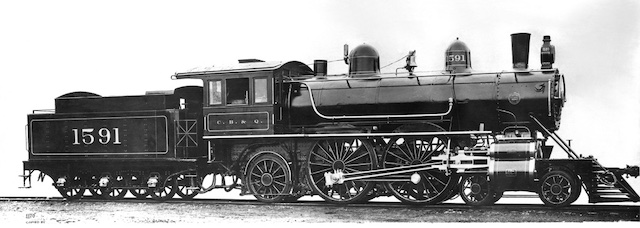

This high-drivered locomotive was delivered to the Burlington on April 7, 1899, just in time for it to pull the “new” train described in the Denver Post article. Photo from Chuck Zeiler collection.

The Post noted that Burlington had received some “unusually heavy locomotives” one of which “has drivers seven feet in diameter.” In fact, Burlington had just acquired five new 4-4-2 locomotives from Baldwin, one of which is shown in a builder’s photo above. The drivers were actually a half inch bigger than seven feet and just two inches smaller than those of the New York Central’s famous 999.

These engines produced only about 15,000 pounds of tractive effort, but that was sufficient to pull five- or six-car passenger trains up the average 0.1 percent grade from Chicago to Denver. Counting all stops, Burlington’s fastest Chicago-Denver train averaged 35 mph, but in non-stop segments between cities the new locomotives could pull passenger trains faster than 65 miles per hour. These allowed the Burlington to match Union Pacific times and both of these railroads left the Rock Island, whose trains were still taking 34-3/4 hours from Chicago to Denver, and Santa Fe, which had managed to reduce times to 41 hours, in the dust.