In April, 1900, the fastest Burlington and Union Pacific Chicago-Denver trains were speeded up to about 27-1/2 hours. That was a big improvement over 1890, when the fastest trains were over 30 hours, and an even bigger improvement over 1882, when the fastest were over 45 hours.

Click image to download a 252-KB PDF of this postcard.

Click image to download a 252-KB PDF of this postcard.

For some reason, however, these improvements stopped almost until the age of streamliners. In 1930, the fastest trains were still about 27-1/2 hours. In 1935, Burlington’s fastest eastbound train took 25-1/2 hours, but the westbound train still took 27-3/4 hours.

The Rock Island, meanwhile, managed to incrementally improve its times until it too could carry passengers between Chicago and Denver in 27-1/2 hours. However, it took until 1931 to reach that mark; as of 1929, for example, it was still over 30 hours.

Santa Fe was even worse, with its single Chicago-Denver train taking 41 hours from 1900 through to at least 1928. Santa Fe passengers willing to change trains could get from Chicago to Denver a little faster. For example, in 1928 the Navajo to La Junta connected with a train to Denver that required a total of 33-1/4 hours, still about 5 hours longer than the competitors’ through trains.

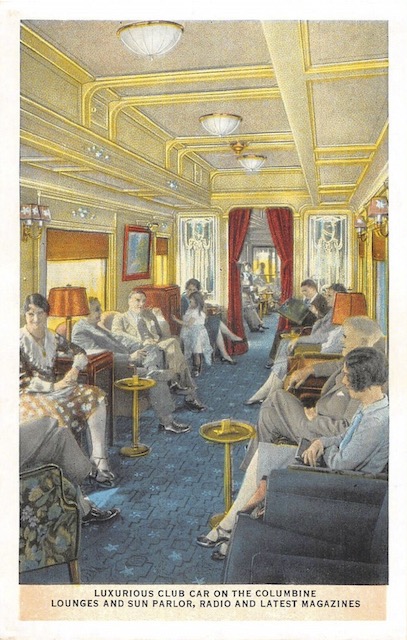

Instead of competing on speed, the railroads competed on luxury. In 1927, Union Pacific introduced the Columbine, or rather renamed the Colorado Special, as the two trains had the same numbers. What the Columbine had was a luxurious observation-lounge car that went the entire distance between Denver and Chicago. The Colorado Special also had an observation car, but it only went part way.

The Columbine‘s observation car included a compartment and drawing room. This left space for a women’s lounge, a smoking room (men’s lounge), a general lounge with 15 seats, and an observation room with 8 seats. Both the lounge — as shown in the above postcard — and the dining car were liberally decorated with carved images of columbines, Colorado’s state flower.

In 1930, Burlington finally used an evocative name when it re-equipped the Colorado Limited (our old friend trains #6 & 9) and gave it a new name: the Aristocrat. This was advertised as providing “new travel luxury” including, among other things, a full-length observation car.

Unlike the Columbine‘s observation car, none of the space in the Aristocrat‘s car would be used for revenue drawing rooms or compartments. Instead, it had a large parlor lounge with 12 seats at one end, a card room and buffet in the middle, another parlor lounge with 15 seats near the back, and an 8-seat solarium lounge.

Union Pacific responded by providing the Columbine with a full-length observation of its own. The car had a barber shop, shower bath, and buffet at one end, and a six-seat solarium lounge at the other. Most of the car, however, was one long lounge with 37 comfortable seats in a variety of configurations.

Click image to download a 2.9-MB PDF of this 20-page booklet.

Click image to download a 2.9-MB PDF of this 20-page booklet.

This upped the ante for the Burlington, whose original Aristocrat didn’t include a barber shop or shower bath. As shown in the above booklet, however, Burlington quickly added a barber/shower to the center of the observation car in place of the card room.

One curious thing about the above Aristocrat booklet is a statement that “The 1935 Aristocrat is the 48th annual edition of the oldest long-distance train in America.” Of course, the name “Aristocrat” was only 6 years old in 1935, so in what sense was this train 48 years old? Burlington first operated Denver-Chicago train service in 1882, which would make 1935 the 53rd annual edition. In what sense was this the oldest long-distance train? The Broadway Limited could trace its history back to the New York and Chicago Limited in 1881. This is just one more piece of hyperbole issued by Burlington’s marketing department.

The Depression led Santa Fe to discontinue trains 5 & 6. But in 1932 luxury-oriented passengers could take Santa Fe’s premiere train, the Chief, to La Junta and connect with a morning train to Pueblo, which connected to another train to Denver, taking a total of 27 hours and 50 minutes. This was just 10 minutes more than the Aristocrat or Columbine, but not only required two changes of trains but an extra fare to ride the Chief.

In the early 1930s, an uneasy peace prevailed for the other three railroads with Chicago-Denver lines. All three had two major trains each day, one taking about 27-1/2 hours and the other a little over 30 hours. The faster train for each had a full-length observation car. The slower train for each had a observation-sleeping car with 10 sections, leaving room for an observation parlor but no barber, shower baths, or smoking/card rooms.

That peace was broken in 1936 when Burlington introduced the Advanced Denver Zephyr in June and Union Pacific introduced the City of Denver 18 days later. Both trains covered the distance between Chicago and Denver in about 16 hours, or at least 10 hours faster than most of the trains preceding them.

Financially ailing Rock Island, which had gone bankrupt in 1914 and again in 1933, responded late with the Rocky Mountain Rocket in 1939. While this train was beautifully streamlined, it was unable to meet the pace of its competitors and took 19-1/2 hours from Chicago to Denver and 18 hours 50 minutes back. The best Santa Fe could do was the streamlined Chief connecting with trains at La Junta for a Chicago-Denver time of 25-1/2 hours.