The 19th-century timetables recently presented here revealed that passenger train speeds in the 1870s averaged about 18 miles per hour including stops. Two decades later, the New York Central was running a passenger train that averaged more than 50 miles per hour including stops.

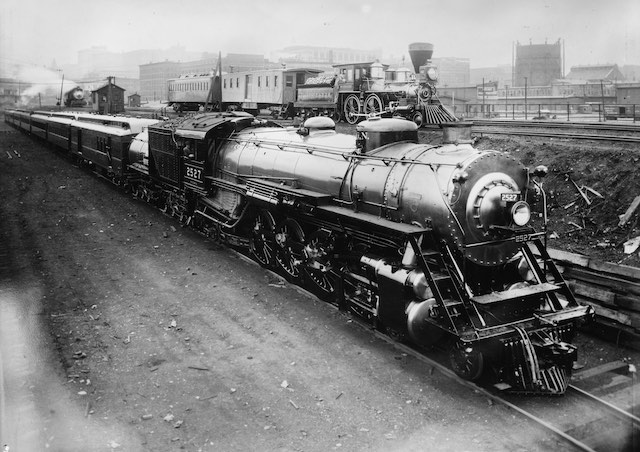

In 1924, Great Northern put the New Oriental Limited on display in Chicago alongside of its oldest train, the William Crooks and two passenger cars from the 1860s. Click image for a much larger (7.3-MB) view. Click here for a beautiful colorized version of this photo by Mike Savad.

The Empire State Express was exceptional. The fastest trains on most routes around the turn of the century averaged about 30 to 35 mph, but that’s still close to double the speed of trains in the 1870s. This growth in speeds was partly due to faster, more powerful locomotives but also to the introduction of limited trains that made fewer stops.

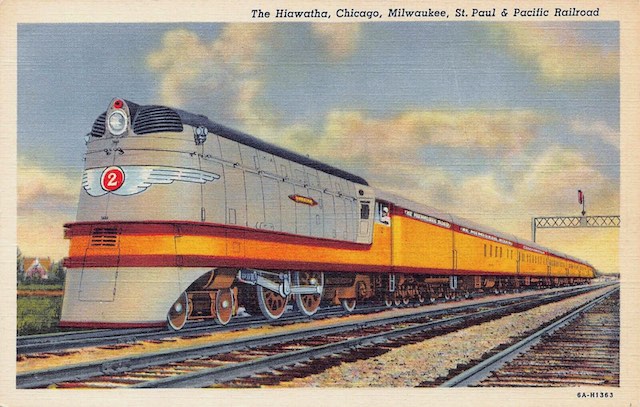

Another increase in speeds took place during the streamliner era. Several trains including the 20th Century Limited, Hiawatha, and Twin Zephyrs averaged better than 60 mph, while the City of Los Angeles and Super Chief weren’t far behind.

When I started writing about all-steel trains and superpowered locomotives (meaning locomotives with large fireboxes, superheaters, and mechanical stokers), I presumed that this transition saw a similar increase in speeds between about 1900 and 1925. Instead, despite the introduction of larger, more powerful locomotives, this period saw little or no increases in average train speeds. For example, the 2527 in the image above weighs almost six times as much as and is more than ten times more powerful than the William Crooks, yet most of the speed gains since the Crooks were obtained with much smaller locomotives between 1862 and 1900, not with the larger locomotives built after 1910.

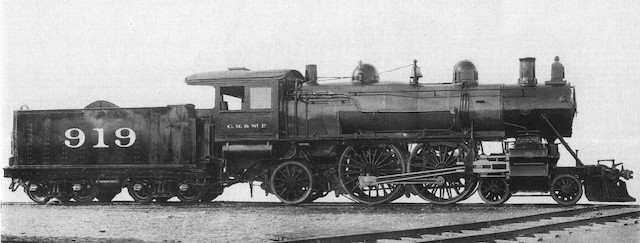

This locomotive was the height of passenger steam locomotive technology when it was built in 1901, a year before the first rail 4-6-2 locomotive was made. With 200 pounds of boiler pressure and 84″ drivers capable of speeding a train close to 100 mph, this and similar locomotives made it possible for the railroad to run fast mail trains between Chicago and Minneapolis in 10 hours and 40 minutes, three hours faster than trains before it. Click image for a larger view.

To understand why this is, compare the above 4-4-2 locomotive, which was built by Baldwin for the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul in 1901, with the 4-8-4 below, which was also built by Baldwin for the Milwaukee Road in 1930. The 4-8-4 weighs 2.3 times as much as the 4-4-2 and it is 3.3 times more powerful as measured by tractive effort. So at first glance it might seem reasonable that trains pulled by the 4-8-4 would go significantly faster than ones pulled by the older locomotive.

Milwaukee ordered this locomotive from Baldwin in order to compare it with 4-6-4 locomotives it had recently received from Baldwin. It was 37 percent more powerful than the 4-6-4s, but it would be seven more years before the Milwaukee would order any more 4-8-4s. Click image for a larger view.

In fact, they didn’t, and it is largely due to one key dimension: driver diameter. The 919 had 84″ drivers, while the 9700 had only 74″ drivers. Using the rule of thumb that locomotives could cruise 10 mph faster than their driver diameter in inches, that meant that the older locomotive could speed some 10 miles per hour faster than the newer one. Admittedly, improvements in valve gear might have helped overcome the 4-8-4’s driver-size envy, but only by enough to make 1930 trains as fast, not faster, than in 1902.

To make a broader comparison, I went through the steamlocomotive.com database to compare the driver diameter, tractive effort, and year of construction for every 4-4-2, 4-8-2, and 4-8-4 locomotive built for U.S. standard-gauge railroads.

More than 80 percent of Atlantic-type locomotives were built between 1900 and 1910. Their driver sizes averaged 78″ and more than 15 percent of them had drivers larger than 80 inches in diameter. The largest were 86 inches, almost the size of 86-1/2″ drivers on New York Central’s 999. The average tractive effort of the 4-4-2s built during this time period was about 23,250 pounds.

By comparison, the 1,854 Mountain-type locomotives built between 1911 (their first year) and 1930 had tractive efforts that averaged more than 57,700 pounds, yet none had drivers larger than 74″ and the average was 70″. The 351 Northerns built in 1930 or before produced an average of more than 63,000 pounds of tractive effort, but only 14 of them had 80″ drivers; the average was just 72″. In all of history, the largest driver size for any 4-8-2 built for an American railroad was 75″ and for any American 4-8-4 locomotive was 80″.

The railroads were clearly not interested in using the larger, more powerful locomotives that appeared after 1910 to increase passenger train speeds. Instead, they put that power to work pulling longer, heavier trains.

This turned out to be a mistake, especially after 1920. Despite a booming economy, from 1920 to 1929 intercity passenger train ridership dropped by 40 percent (and then another 45 percent in the first four years of the Depression). Railroaders of the day frequently bemoaned the “passenger-train problem,” often blaming it on buses when in fact the Model T and other private automobiles were the real competitor.

It wasn’t until well into the Depression that railroads woke up and significantly increased passenger train speeds. In 1935, the Chicago & Northwestern was the third railroad to introduce high-speed passenger service and the Milwaukee Road was the fifth, and they both used steam locomotives to do it. On January 2 of that year, C&NW introduced the 400 powered by 4-6-2 locomotives that had been built in 1923 with 79″ drivers and 45,823 pounds of tractive effort.

The main concession to speed was that the locomotives had been altered to burn oil, not coal, thus allowing them to make the entire trip from Chicago to Minneapolis without refueling. While not common in the Midwest, oil-burning locomotives date back to 1900 and by 1915 there were more than 4,000 of them. C&NW’s locomotives were able to pull a heavyweight train faster than 90 miles per hour and able to connect Chicago and St. Paul in 6-1/2 hours, a huge cut from the 10-hour schedules it had previously been running and which it began running as early as 1899.

In 1935, Milwaukee turned to the seemingly obsolete Atlantic-type locomotive to pull its high-speed Hiawathas. Click image to download a 230-KB PDF of this postcard.

At first glance, the Milwaukee Road’s entry was much more radical. It used home-built streamlined cars painted an eye-catching orange and maroon. Yet to pull this train, it went back in history to order 4-4-2 Atlantic-type locomotives from Alco. A streamlined shroud over the locomotive left the 84″ drivers partially exposed. Like the C&NW Pacifics, the Hiawatha locos burned oil.

If the New York Central 999 was the first locomotive built to go more than 100 mph, the Milwaukee Hiawathas were the first to regularly sustain more than 100 mph over long distances. On a demonstration run on May 8, 1935, the locomotive pulling a seven-car train was able to maintain 112-1/2 miles per hour for 14 miles. According to Alco locomotive designer Alfred Bruce, the locomotive on other runs had pushed above 128 mph — how much above no one knew because the speedometer only went to 128.

Other than the fuel, the main differences between this locomotive and the 919 shown above are the weight and 300 pounds of boiler pressure instead of 200. Most railroad tracks of 1902 weren’t heavy enough to support the weight of the Hiawatha locomotive, but that was remedied by the early 1920s. Delaware & Hudson had a locomotive with 300 psi boiler pressure in 1927, and other railroads had 300 psi boilers in 1930, so the technology behind the Hiawatha locomotives was within reach for several years before being employed by the Milwaukee in 1935.

Both C&NW and Milwaukee were able to meet the same 6-1/2 hour schedules between Chicago and St. Paul that were set by the Diesel-powered Twin Zephyr. The technology behind the C&NW train had been available for at least two decades and the Milwaukee loco could have been built by at least 1927, yet the railroads ignored such possibilities before the introduction of the streamliners in 1934.

While faster trains in 1935 and later helped revitalize their passenger business for a little while, it wasn’t enough to prevent its further decline in the 1950s. Railroads’ failure to significantly increase passenger train speeds in the face of automotive competition in the 1920s may have been one of the great missed opportunities of the 20th century.