In 1900, every streetcar, rapid transit car, and intercity rail passenger car in America was made primarily out of wood. The wheels, trucks, and couplers were metal, of course, but the frame, body, roof, floor, and other components were wood. In 1904, Railway Age magazine asked railroad executives around the country if they thought the underframes of passenger cars should be made out of steel and received almost universal negative responses. Steel wouldn’t protect passengers from accidents, the officials argued; instead, it would only add weight and cost without adding any benefits.

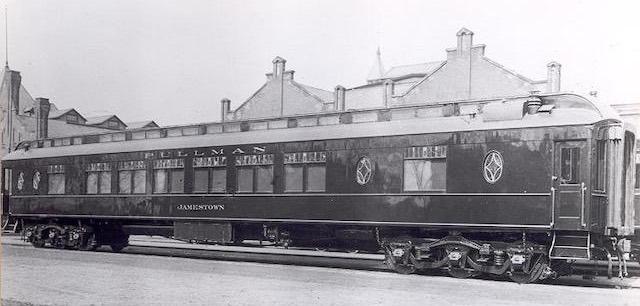

In 1907, Pullman displayed its first all-steel sleeping car at the Jamestown Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia. The Pennsylvania Railroad soon asked Pullman to make 500 sleeping cars for use on PRR trains. Click image for a larger view of this photo from Ingenium, Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation.

In 1907, Pullman displayed its first all-steel sleeping car at the Jamestown Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia. The Pennsylvania Railroad soon asked Pullman to make 500 sleeping cars for use on PRR trains. Click image for a larger view of this photo from Ingenium, Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation.

What changed the industry’s collective mind was not the derailments or collisions but the threat of fire, and in particular fire in tunnels. In 1904, New York City was building the nation’s first subway; the Pennsylvania Railroad was building tunnels under the Hudson River to bring its trains into Penn Station; and Pennsylvania subsidiary Long Island Railroad was building tunnels under the East River to bring its commuter trains into Manhattan.

If Ralph Budd — who first combined Diesel power, air conditioning, and stainless steel into one train — was the godfather of the streamliner revolution, then the godfather of the all-steel revolution was Alexander Cassatt, who was president of the Pennsylvania Railroad from 1899 to 1906. As New York City was building its first subway and the Pennsylvania was planning its tunnels under the Hudson, Cassatt made it clear to George Gibbs, his chief engineer in charge of electric traction, that he believed that only all-steel cars should be used in any of these tunnels. That was astoundingly brave considering that no one had ever built an all-steel passenger car before that time.

The fear of fire was particularly great in New York’s tunnels because the trains were to be electrically powered, and letting sparks from a third rail or overhead wires fly around wooden cars did not seem wise. In 1902, Cassatt directed Gibbs to offer his services to the Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT), which would operate the subway trains, to design an all-steel subway car. This wasn’t entirely altruistic as much of what Gibbs would learn in designing such a car could be applied to all-steel cars for the Pennsylvania Railroad.

IRT was eager to use all-steel cars for its subway. It wasn’t certain, however, that there would be time to design and build a fleet of such cars before the subway opened in 1904, so initially it bought “composite” cars, wooden cars overlain by copper sheathing. The need for all-steel cars was affirmed when several of these cars were completely destroyed in a 1905 fire. The surviving composite cars were soon relegated to elevated lines only.

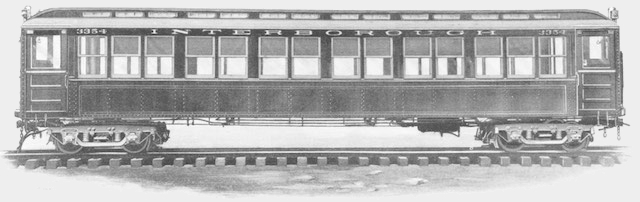

One of IRT’s “Gibbs cars,” the first all-steel cars put into regular use in the world.

One of IRT’s “Gibbs cars,” the first all-steel cars put into regular use in the world.

Gibbs’ designed the first all-steel IRT car and had a prototype built in PRR’s Altoona shops in 1903. Although the car was a little too heavy for subway usage, Gibbs and IRT found ways to reduce the weight and IRT ordered 300 of the redesigned cars from American Car & Foundry (ACF) in 1904, and 160 more later. These became known as Gibbs cars. Long Island Railroad also ordered 134 Gibbs cars from ACF in 1904.

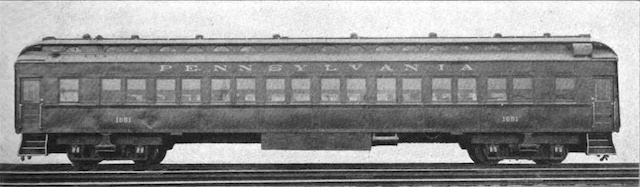

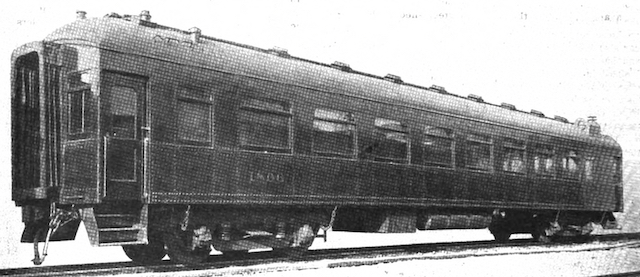

Pennsylvania’s first all-steel coach didn’t look a lot different from its wooden coaches.

Pennsylvania’s first all-steel coach didn’t look a lot different from its wooden coaches.

For its own use, PRR built an all-steel car that, with some modifications, became the P-70 coach (70 because the interior passenger compartment was 70-feet long; the entire car was 80 feet). Having settled on a design, in 1907 it ordered 90 such cars from ACF (which claimed to be the “the only car builders willing to undertake so large a contract on a fixed price basis”), and continued to order more so that for the next several years ACF was almost continuously building such cars for PRR on top of cars PRR built in its own shops.

By January 1910, PRR had 324 all-steel cars and was able to make an entire all-steel train including baggage, coaches, diners, and sleeping cars. Manhattan’s Penn Station opened on November 17, 1910, by which time the railroad had enough cars to serve all of its trains running in and out of that station.

The sleeping cars were made by Pullman, which had built its first all-steel sleeping car, the Jamestown, in 1907. This led PRR to ask Pullman to make more than 500 steel sleeping cars for operation on Pennsylvania Railroad trains. These were completed by the end of 1912, by which time Pennsylvania had almost 2,900 of its own all-steel cars (including Long Island Railroad cars) in operation.

In 1916, the Pennsy began calling itself “the standard railroad of the world.” Its leadership in promoting the all-steel revolution demonstrated the truth of that slogan.

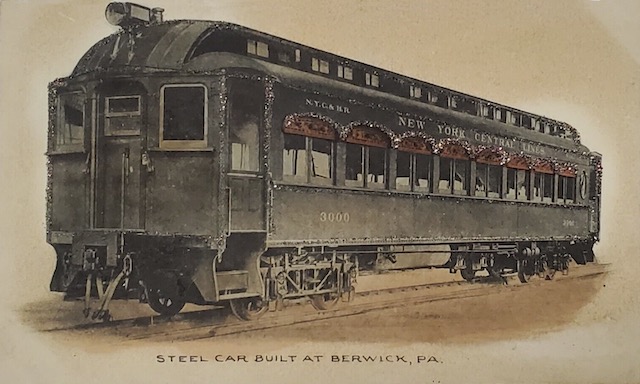

American Car & Foundry’s first all-steel car for the New York Central in 1905 or 1906. Click image to download a 1.1-MB PDF of this postcard.

Other railroads experimented with all-steel cars. In 1905, New York Central ordered some all-steel cars from American Car & Foundry (which had a factory in Berwick, Pennsylvania). Though the railroad would buy 125 such cars from ACF by 1910, it didn’t feel as pressured to replace its fleet of wooden cars as it didn’t have to deal with the Hudson River tunnels used by the Pennsylvania.

In 1905, Erie ordered a few all-steel cars for handling mail. “The great strength of these cars, with their comparatively small increase in weight, and their fire proof qualities, should render the type valuable,” said Railway Age. This was proven a year later when one of those cars was in an accident. It “plunged down 12-foot embankment,” reported Railway Age. “The car turned over three times, but was very slightly damaged” while several wooden cars that were in the same accident were “badly smashed. This is the first steel passenger car to go through a wreck in this country and the favorable showing will tend to further encourage the use of steel.”

When building its first all-steel coach in 1906, SP also experimented with an innovative roof line. Click image for a larger view of this photo from page 380 of the September 28, 1906 issue of Railway Age.

When building its first all-steel coach in 1906, SP also experimented with an innovative roof line. Click image for a larger view of this photo from page 380 of the September 28, 1906 issue of Railway Age.

In 1906, Southern Pacific built a 60-foot all-steel coach in its Sacramento shops. Instead of the clerestory roofs that were standard on wooden cars (and PRR’s P-70 coaches), SP installed a semi-elliptical roof, which became the prototype for the Harriman cars used by IC, SP, UP, and other Harriman-controlled railroads.

By 1910, ACF, which had up to that point built nearly 90 percent of all all-steel cars in the country, had built 125 cars for New York Central, 99 for Rock Island, 40 for the Frisco, 5 for Missouri Pacific, a demonstrator car for the Lackawanna, and several cars for other railroads.

The U.S. Railroad Passenger Car Fleet

| Year | Wood | Steel Frame | All-Steel | Total | % All-Steel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 44,900 | 1,100 | 1,100 | 47,100 | 2.3% |

| 1915 | 40,000 | 5,200 | 10,800 | 56,000 | 19.3% |

| 1920 | 34,500 | 6,500 | 15,100 | 56,100 | 26.9% |

| 1925 | 26,200 | 9,400 | 21,200 | 56,800 | 37.3% |

| 1930 | 15,100 | 10,400 | 29,000 | 54,500 | 53.2% |

| 1935 | 5,000 | 8,400 | 29,000 | 42,400 | 68.4% |

| 1940 | 2,000 | 6,400 | 29,900 | 38,300 | 78.1% |

| 1945 | 1,400 | 5,400 | 31,800 | 38,600 | 82.4% |

| 1950 | 300 | 3,500 | 33,500 | 37,300 | 89.8% |

These numbers only include railroad-owned cars, not Pullman cars. A third of Pullman cars were all-steel by 1915. This reached 80 percent by 1930 and more than 98 percent by 1940. Source: White, The American Railroad Passenger Car.

In 1910, the Harriman lines — IC, SP, & UP — placed an order for 650 steel cars, announcing that they would no longer buy wooden cars. Santa Fe purchased some wooden cars with steel underframes in 1911, saying that it was hard to insulate all-steel cars from the outside weather. One railroad executive alleged that they were “ice cream freezers in winter and bake ovens in the summer.” Yet it is doubtful that any wooden cars were built in the U.S. after 1912, and even Santa Fe began using all-steel cars on its premiere trains in 1913.

All-steel cars weighed more than wooden cars, but the difference was not great. A 53-foot wooden coach weighed 85,000 pounds; a similar steel car weighed 95,400. A 70-foot wood coach weighed 106,000; steel was 116,100. Part of the differences in weight was due to the fact that the wooden coaches were generally lit by Pintsch gas while the steel cars were lit by electricity, and storage batteries for the electricity added several thousand pounds to the total.

Initially, industry experts believed that steel cars would cost about 20 percent more than wooden ones. However, by 1912, the cost of wood products had increased while the industry’s experience building steel cars had reduced costs, so the two cost about the same.

According to one archived web site, a 1906 train crash in the District of Columbia that killed 53 people led the Interstate Commerce Commission to ban “wooden body passenger car construction.” I haven’t been able to verify this; the closest I can come is that in 1912 the ICC asked Congress to consider legislation hastening the adaptation of steel cars. Although Congress that railway post office cars be made of steel, thus protecting federal employees, any further legislation was defeated. In any case, the last wooden cars were made in 1913, so any ban would have had to come after that and probably didn’t matter since the industry by then was pretty much sold on steel cars.

The all-steel car fleet rapidly grew, but like the streamliners, steel didn’t completely replace wood cars for many decades. The Long Island Railroad was the first to completely retire its wooden cars, but not until 1927. Pennsylvania and other railroads continued to use wooden cars on branch lines for many years, but by 1925, pretty much all limiteds and other major intercity passenger trains had been converted to all-steel cars.

Information in this post is mostly based on research in back issues of Railway Age that are downloadable from Google Books.