When Donald Smith drove Canadian Pacific’s last spike in 1885, the city of Vancouver did not yet exist and Port Moody, the railroad’s original terminus, housed only about 250 people. All of British Columbia held about 50,000 residents, half of which were indigenous peoples who were unlikely to make much use of the railroad, and many of the rest didn’t live anywhere near the railroad. Alberta and Saskatchewan combined had even fewer residents and Manitoba didn’t have many more.

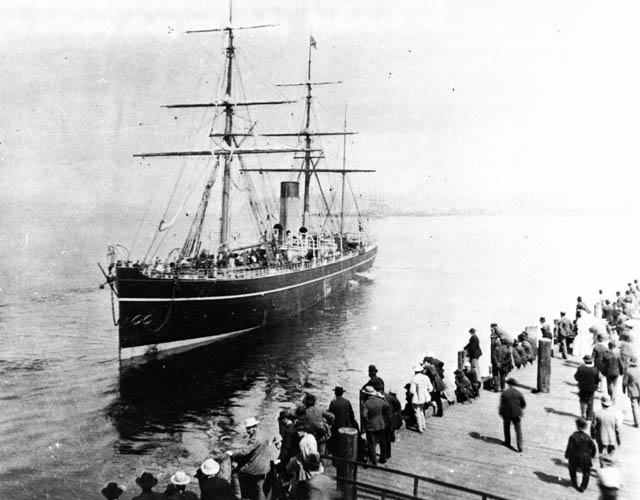

Canadian Pacific enters the steamship business as the Abyssinia leaves Vancouver on its maiden voyage in 1887. Built in 1870, the ship has three masts for sails as back up in case of engine failure. Click image for a larger view from the Chung collection.

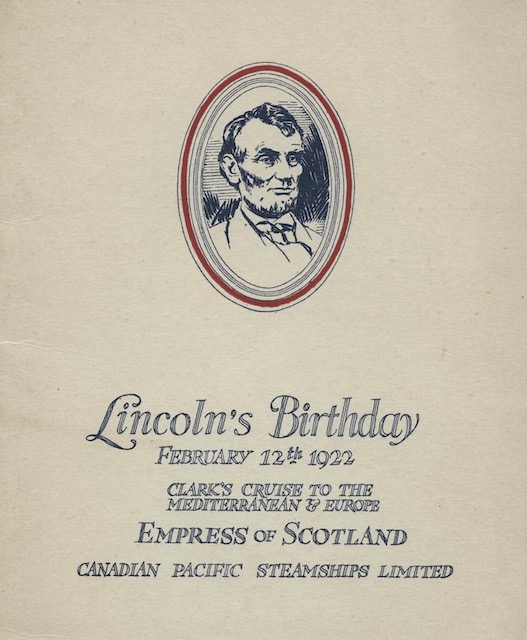

The railroad’s first problem, then, was to generate enough business to keep its engines lubricated. One way of doing so was to open up trade with the Far East so that the railroad could become a transportation link between Europe and Asia. To promote this link, Canadian Pacific leased three ships that had been built in 1870 for the Cunard Line. These ships were obsolete in Atlantic service, but were better than anything that had been seen before between Canada and Japan. CP put them to work between Vancouver and Yokohama. Continue reading