To promote construction of a northern railway, Congress in 1864 offered the most generous land grant in U.S. history: roughly 44 million acres consisting of every other square mile of land within 20 miles on either side of the rail line in Minnesota and within 40 miles on either side between Minnesota and Puget Sound. Moreover, if some of the lands had already been claimed (such as lands within an Indian reservation), NP was allowed to choose any other lands it wanted within 50 miles of the rail line.

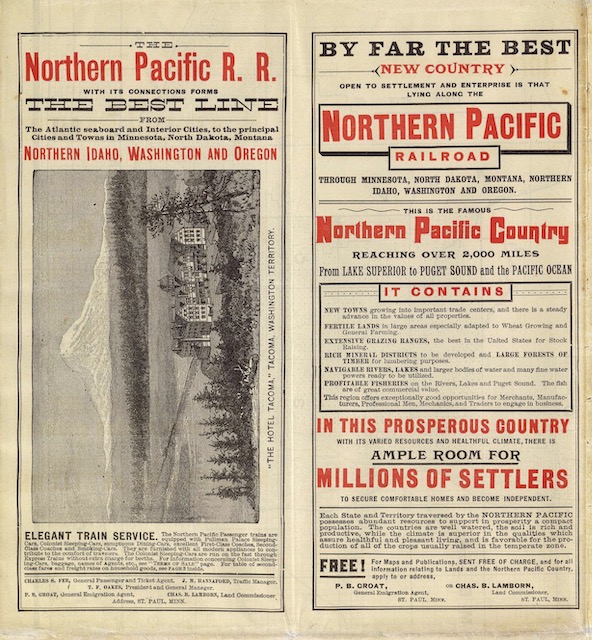

Click image to download a 13.2-MB PDF of this brochure, which is from the David Rumsey map collection.

Click image to download a 13.2-MB PDF of this brochure, which is from the David Rumsey map collection.

This was a far more generous land grant than for any other railroad. The first railroad land grants gave every other square mile of land within six miles of the railroad to the Illinois Central and Gulf, Mobile & Ohio between Chicago and New Orleans. The other transcontinental railroads (Union Pacific, Central Pacific, Southern Pacific, and Santa Fe predecessor Atlantic & Pacific) received every other square mile within 20 miles of the lines.

Not surprising, when measured in acres Northern Pacific’s grant dwarfs the grants to other railroads. According to a 1962 tally by the Library of Congress, the Southern Pacific was granted 27.6 million acres (including the Central Pacific grant) and received 22.3 million acres. The Santa Fe and its predecessors were granted 17.1 million acres of which they eventually received 15.1 million. Union Pacific and its predecessors (Kansas Pacific, Denver Pacific, etc.) were granted 20.5 million but received about 8 million. Chicago & North Western also received about 19.4 million. Illinois Central, Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul, and Missouri Pacific were each granted more than 5 million but ultimately received less than 5 million. No other railroad received more than 4 million.

The amounts the railroads received were different from the grants because the number of miles of rail lines built usually differed from the original estimates. In some cases, Congress took the lands back because the railroads failed to comply with the terms of the land grant. In fact, none of the railroads complied with the terms, but the political will to take back the lands was only exercised in a few instances.

Congress’ reasoning behind the land grants was that land in the West was worthless without transportation, and that giving every other square mile to the railroads would double the value of the remaining land, thus costing the federal government nothing. The flaw in this logic was that, even with the railroads, the land wasn’t worth much and the feds couldn’t find any buyers. It gave away some land to homesteaders and ended up keeping a lot of the land, which eventually became national forests and other public domain.

The NP’s grant per mile of rail line was double that of any other railroad supposedly because the NP was going through more desolate territory. Members of Congress probably thought it was desolate because it was further north. In fact, from the wheat farms of Minnesota and North Dakota to the tall timber of the Pacific Northwest, the lands along the NP were arguably more productive, on average, than lands along the more southerly transcontinental routes.

Some members of Congress almost immediately regretted giving NP such a large grant and made several efforts to rescind it. In 1890, it took back about 3 million acres of land that the NP hadn’t yet claimed. That led to years of litigation that ultimately left the company with 39.9 million acres, which was nearly twice what any other railroad received and more than 30 percent of all the land grants given by Congress for railroad construction.

This 1888 brochure advertises 40 million acres of land for sale from Minnesota to Washington for $2.60 to $6.00 per acre (about $90 to $200 today). It also notes that government lands were available for homesteading of up to 160 acres per person (or 320 acres per couple) at no charge other than an $18 to $22 filing fee (which is about $600 to $700 today).

The detailed map on the back of the brochure shows NP and government lands in western Washington and northwest Oregon with indications of which lands had already been sold and which were still available. Much of the land in this area was covered with old-growth timber that would become valuable after World War II but was practically worthless in 1888 due to the abundance of forests. Nor was much of the land suitable for farming due to steep slopes.

As a result, most of the land was still unsold in 1900, by which time James J. Hill had gained control of the Northern Pacific. In January of that year, Hill sold 900,000 acres of timber land, mostly in Washington state, to his next-door neighbor, Frederick Weyerhaeuser, for $5.4 million or $6 an acre. This formed the basis of what would become one of the largest timber companies in the world.

NP still had several million acres of timber land in Idaho and Montana that eventually was spun off into the Plum Creek Timber Company. In 2015, Weyerhaeuser bought that company, making itself the nation’s largest private landowner with a total of 13 million acres (since shrunk to 11 million).