The recent posts about the Northern Pacific land grant and Red River Valley lands provides a good segue to some research I’ve been doing about a land grant in Oregon. This has no passenger train content and is only peripherally related to railroads, but the subject interests me because some of the land grant in question is just a half mile from my home and because one of the major players in the later part of the story was Great Northern Railway president Louis Hill.

This 1939 report from the Department of the Interior lists 105 railroad, wagon road, canal, and river improvement land grants made by Congress in the 19th century and how many acres various transportation companies ended up receiving for those grants. A few of the grants, including the massive Northern Pacific grant, were still open with the grantees hoping to get several million more acres. Click image to download a 4.7-MB PDF of the report.

This 1939 report from the Department of the Interior lists 105 railroad, wagon road, canal, and river improvement land grants made by Congress in the 19th century and how many acres various transportation companies ended up receiving for those grants. A few of the grants, including the massive Northern Pacific grant, were still open with the grantees hoping to get several million more acres. Click image to download a 4.7-MB PDF of the report.

Today I’m going to introduce the topic by describing the history of federal land grants. These land grants have been praised for playing a key role in the development of the nation and derided for being a huge giveaway to corporate interests, but I’ll show that neither of these are really true. Posts tomorrow and the next day will go into the history of the Oregon land grant, followed by two more posts on what happened to the land in that grant. After that I’ll get back to railroad memorabilia.

After the American Revolution, the federal government claimed nearly all of the land between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River. The Louisiana Purchase and lands stolen from Mexico via the Mexican-American War extended this domain to the Pacific Ocean. The federal government once owned pretty much everything west of the original 13 states except Texas and some Spanish land grants in the southwest.

From the beginning the political consensus was that nearly all of these lands should be somehow transferred to private owners. While this seems obvious today, it was one of the more revolutionary ideas to come out of the American Revolution as, at that time, the vast majority of land in almost every other country in the world was owned by the monarch, the government, or a small aristocracy. Indeed, even today, the majority of land in the world, included most land in Africa, Asia, South America, and even Europe is owned by either a government or an oligarchy.

In the United States in most of the nineteenth century, the question wasn’t whether to transfer the lands to private owners but how. Alexander Hamilton hoped to make enough money selling land to pay off the nation’s Revolutionary War debt. But this quickly ran into a problem: most of the land was so remote that it wasn’t worth much.

Before steamboats and steam trains, it cost less money to ship goods from Europe to an American port than it did to haul those goods from the port to 30 miles inland. People living west of the Appalachians would have little access to manufactured goods and little way to economically ship anything they grew to the population on the Atlantic Coast.

Then the state of New York financed the construction of the Erie Canal, which opened in 1825. This reduced the costs of inland shipping by 75 percent and made New York City the nation’s dominant seaport and manufacturing center.

Other states wanted their own canals as well as roads for hauling freight. In 1823, someone came up with the idea of giving federal land to people for building roads or canals. The first grant in 1823 gave the company that built a road a right-of-way for the road plus all of the public lands, one mile in width, on either side of the road.

In 1827, Congress hit upon the idea of giving every other square mile of land on either side of the road or canal, effectively granting one square mile per mile of construction. The transportation improvement would increase the value of the remaining land, which the federal government could then sell. If the transportation doubled the value of the land, the net cost to the government would be zero.

For this and just about every other federal land grant or sales system the land first had to be surveyed. The public land survey system consisted of dividing lands into square miles, called sections. Six-by-six blocks of sections are called townships. Each section in a township is numbered from 1 to 36. Many transportation land grant acts specified that only even- or odd-numbered sections would be given out.

The number of sections of land given per mile of transportation improvement quickly grew from one to three to six to ten and finally reached 20. In addition, if some lands were already in private or other non-federal ownership, the grantees were allowed to pick other lands (usually either even- or odd-numbered sections as specified in the grant) that were within so many miles outside of the main grant.

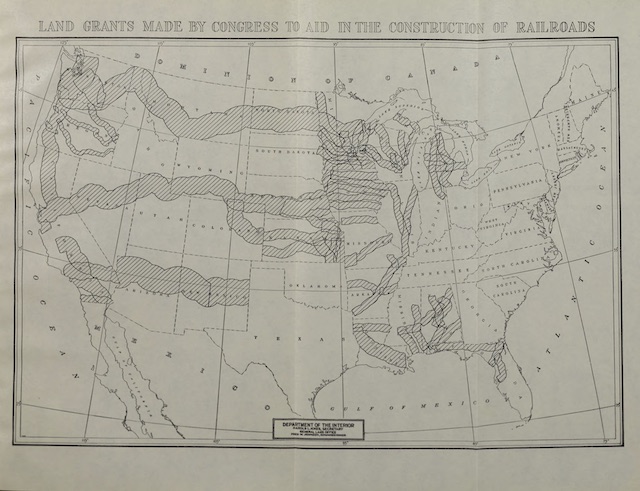

This map, which is from the above report, shows railroad and wagon road land grants, but not canal or river improvement grants. Maps like this exaggerate the amount of land that was given away; in fact, no more than a quarter of the land within the marked areas was generally included in the land grants. Click image for a larger view.

For example, if a grant allowed the transportation company every odd-numbered section within three miles of the improvement, it could also pick other odd-numbered sections that were from three to six miles of the improvement in place of any sections that were already non-federal within the inner three miles. This outer strip was called the indemnification strip. The maps of land grants usually show both the inner and the indemnification strips, so only about a quarter of the land shown on the maps actually was given away in the grants.

Many land grants were not actually intended by Congress to be land grants to private transportation companies. Instead, Congress specified that the grants were to the states, which were to sell them as the transportation improvements were made in 10-mile increments. The problem with this was that federal land surveyors were behind in their work and the transportation improvements were often completed years or even decades before the land was fully surveyed. In practice, the land was almost always simply given to the companies.

In some railroad land grants, Congress specified that the land was to be given to the railroads, not the states, and that the railroads were to sell the lands. Often, the laws required that the lands be sold only to actual settlers in blocks of no more than a certain number of acres, usually 160 acres per person, and for no more than a certain amount, such as $2.50 per acre. The railroads usually ignored these laws, partly because there was no market for much of the land and they wanted to wring every possible dollar out of the lands for which there was a market to help pay for construction.

Apparently, no one knows precisely how many acres Congress gave away in transportation land grants. This 1962 report from the Library of Congress should provide a definitive answer, at least for the railroad and canal land grants, but it actually contains multiple estimates that differ slightly from one another. The closest answer seems to be slightly less than 145 million acres of which a little more than 130 million acres went to railroads. Click image to download a 9.9-MB PDF of the report.

Apparently, no one knows precisely how many acres Congress gave away in transportation land grants. This 1962 report from the Library of Congress should provide a definitive answer, at least for the railroad and canal land grants, but it actually contains multiple estimates that differ slightly from one another. The closest answer seems to be slightly less than 145 million acres of which a little more than 130 million acres went to railroads. Click image to download a 9.9-MB PDF of the report.

In a few cases, local controversies over the land grants and the railroad or other grantee’s failure to abide by the terms of the grants led Congress to consider taking back the lands. The most important example was a grant for an Oregon & California Railroad from Portland to San Francisco along with another grant for a road from Roseburg to Coos Bay, Oregon, which were both owned by the same company. The grants specified that the company was to sell the land for no more than $2.50 an acre in parcels of no more than 160 acres.

The problem with this, as with many other railroad land grants, was that most of the land was steep, forested slopes unsuitable for farming, while 160 acre parcels didn’t make sense for timber management. The railroad therefore sold larger lots sometimes for as much as $40 an acre. When a newspaper uncovered this scandal, it led to indictments of a U.S. senator, two U.S. representatives, and a U.S. attorney, among others. In 1916, Congress took back all of the unsold lands in the grants, most of which are now being managed by the Bureau of Land Management.

The Oregon & California Railroad wasn’t the only company to violate the terms of its grant; it is quite likely that none of the grantees met the terms of their grants. For some reason, however, the O&C was one of the few that had to give its land back.

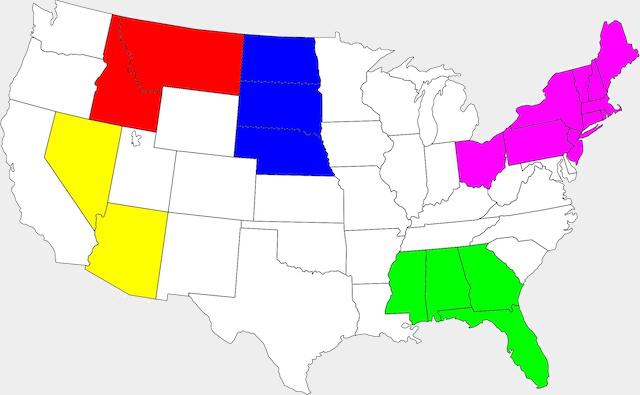

Any of the five colored areas on this map are approximately equal to the area of all the transportation land grants given out by Congress between 1823 and 1869.

In all, Congress made 105 land grants totaling to just under 145 million acres or 226,359 square miles. As the above map illustrates, this is a lot of land but less than 10 percent of the land in the contiguous 48 states once owned by the federal government. Of the land grant acres, 93 percent went to railroads. Wagon roads and river improvements received about 2 percent each while canals received 3 percent.

It is hard to argue that the land grants were a huge giveaway to wealthy interests since the lands were worthless at the time and many of the companies that received them ended up going bankrupt because they were unable to sell enough land to finance the transportation projects they were supposed to build. Nor did the land grants play a critical role in the development of the West since, as James J. Hill proved, many of the railroads would have been built anyway. Instead, the land grants often funded projects that really did not make economic sense at the time.

Many of the railroad land grants were highly questionable. The land grant map shows Iowa blanketed by railroads heading for Council Bluffs. Predecessors of the Burlington, C&NW, Illinois Central, Milwaukee Road, and Rock Island all received land grants to funnel their lines into the Union Pacific, which led to a rate war between those railroads. But these grants were unnecessary as evidenced by the fact that Missouri Pacific and Wabash both built to Council Bluffs without land grants.

Grants to canals and wagon roads were even more questionable. Giving away lands for canals and wagon roads might have made sense in the 1820s, when railroads were still an unknown and unproven technology. In the 1820s, Congress gave wagon road land grants to Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio and one more canal grant to Wisconsin in 1838. In 1850, it started giving out railroad land grants, suggesting that it recognized that wagon road and canal grants no longer made sense.

However, during the Civil War, there was a resurgence in road and canal grants. In 1863, Congress approved a grant of three square miles per mile of wagon road between Fort Wilkins, Michigan and Fort Howard, near Green Bay, Wisconsin. Supposedly, this was for military purposes, but Michigan’s upper peninsula and northern Wisconsin were hardly of military significance at the time.

This was followed by three more canal grants and nine more road grants. The roads were called “military roads” but all were to states distant from the Civil War, namely Michigan, Wisconsin, and Oregon. In fact, during and just after the war, Oregon received 2.5 million acres of wagon road grants, which was almost three times as many acres as all other states combined. Of these, the largest grant was to a company called the Willamette Valley and Cascade Mountain Wagon Road Company, which will be the subject of tomorrow’s post.