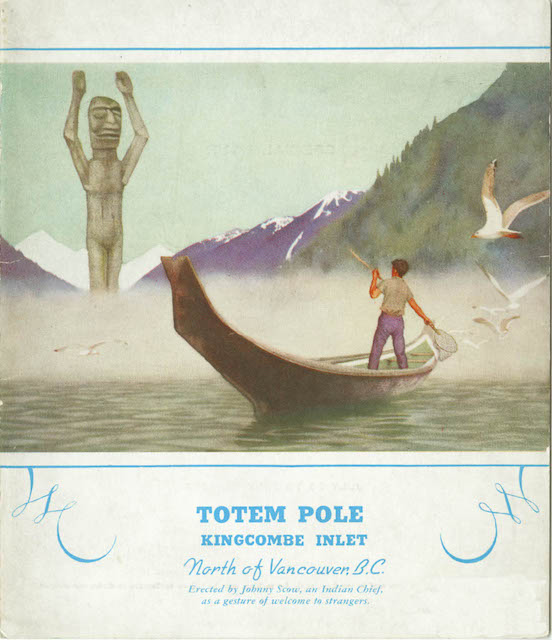

This tri-fold menu features the welcome totem pole at Kingcombe Inlet — which is now apparently spelled Kingcome Inlet — a fjord between Vancouver and Prince Rupert. This totem was at the entrance to a village which once held potlatch ceremonies in defiance of a Canadian ban on such activities between 1885 and 1951.

Click image to download a 798-KB PDF of this menu.

Click image to download a 798-KB PDF of this menu.

This 1967 photo shows the totem with most of its arms missing. I suspect it is completely gone now, but there are some pictographs in the area. Continue reading