Since I began Streamliner Memories in 2012, I’ve posted more than 5,000 documents relating to passenger train history. I’ve now posted almost everything in my own collection and I can’t help but wonder: what should I do now? For example, could I turn this web site into a book? I’m hoping you can help answer this question.

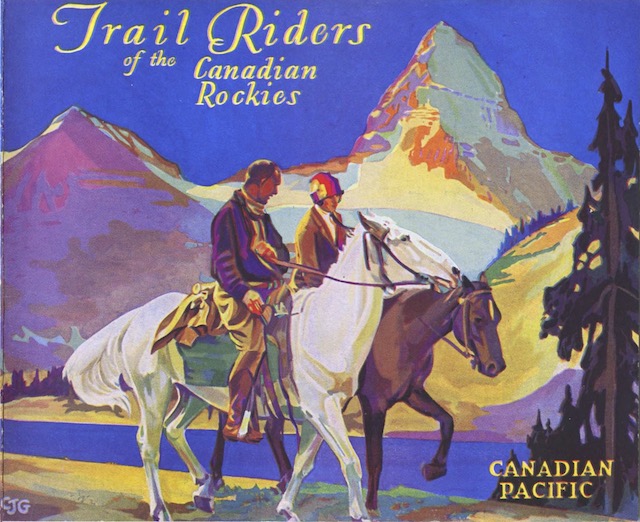

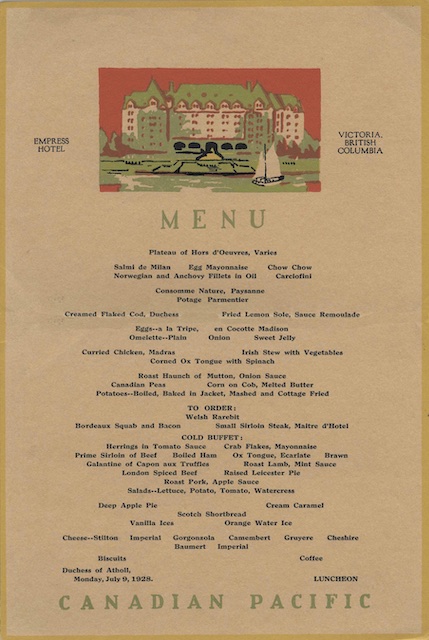

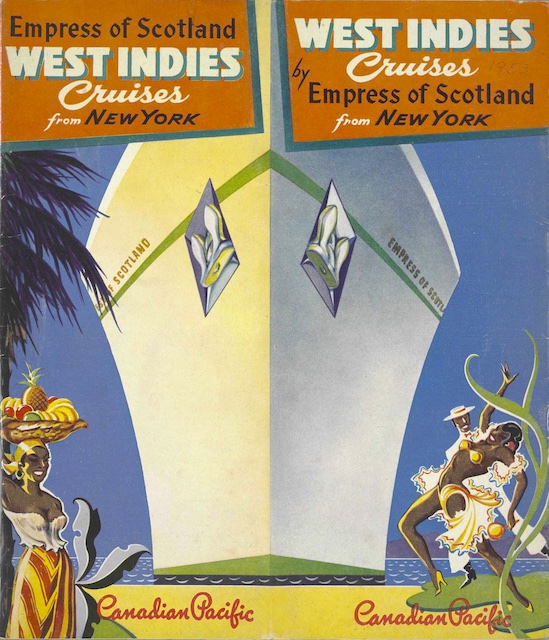

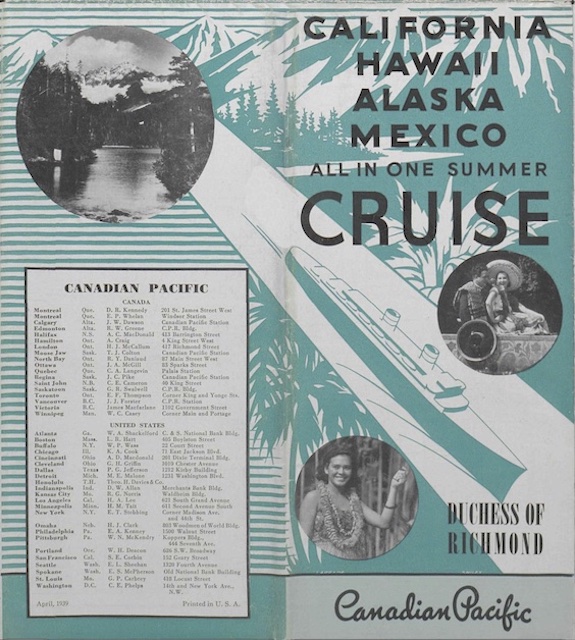

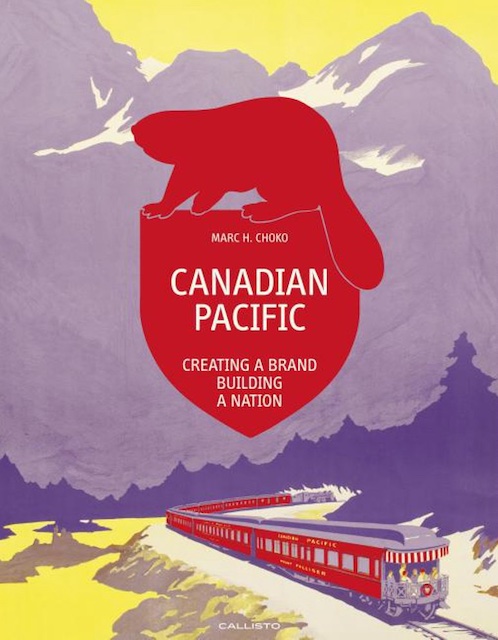

I started to think about this when I learned that Marc Choko, who co-authored two books on Canadian Pacific posters that I frequently use as references, has also written a much larger book: Canadian Pacific: Creating a Brand, Building a Nation. A publisher named Callisto released this 384-page book in three increasingly sumptuous editions, all of which are available from various book dealers. The standard edition, shown above, is 9″x12″, weighs 4 pounds, and originally sold for $70. Continue reading