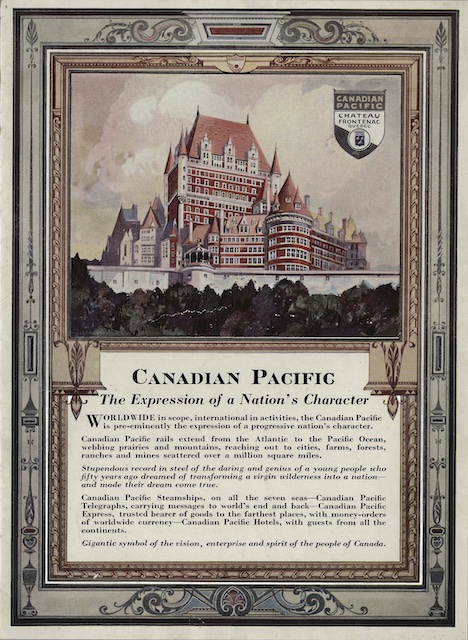

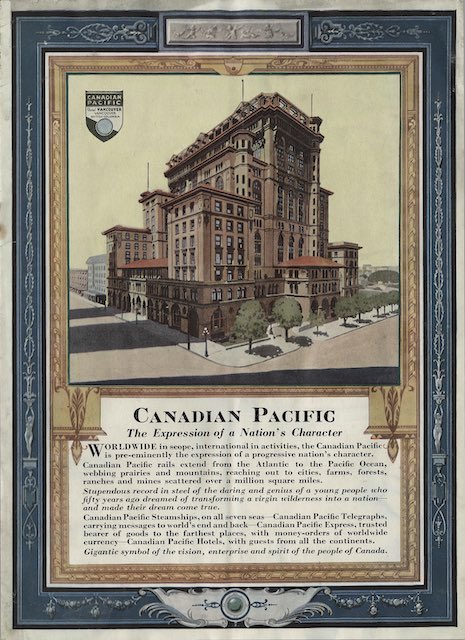

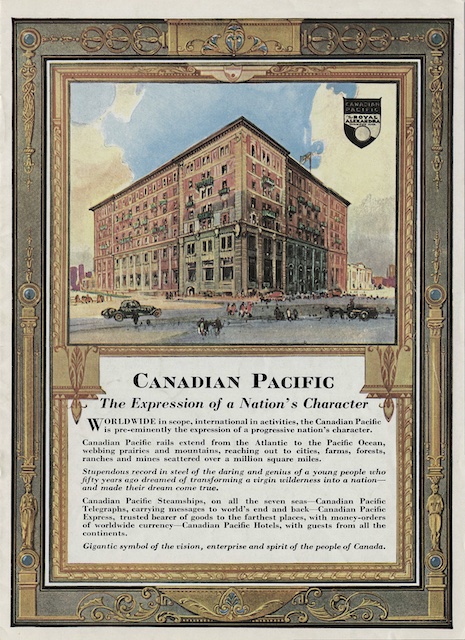

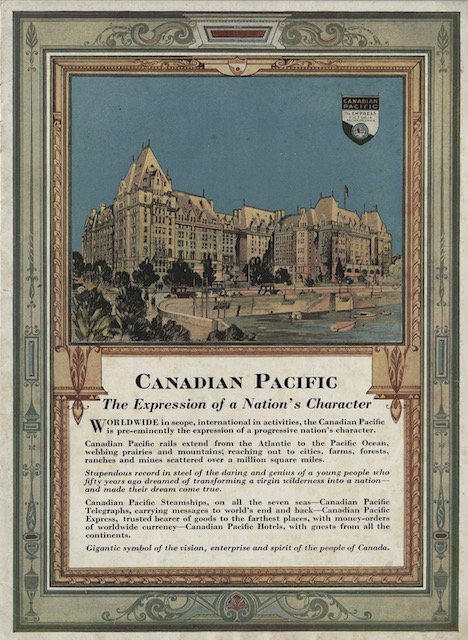

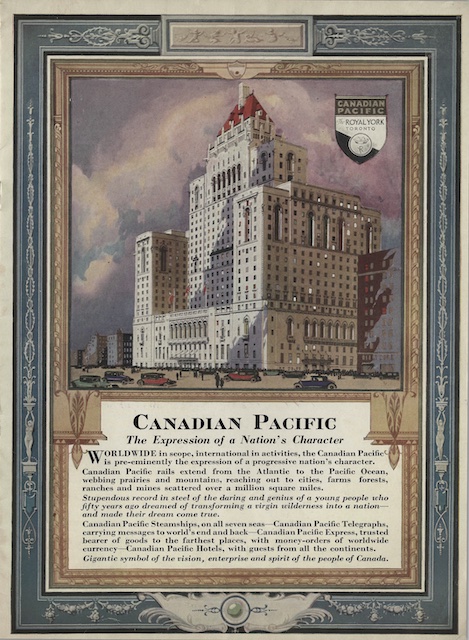

The York Hotel was brand-new when this series of booklets and menus was published, having opened in June, 1929. The Canadian Pacific should have made this opening of the facility it billed as the “largest hotel in the British Empire” in the forefront of its advertising. Instead, like its other hotels, it is lost in this Expression series in which the railway is trying to define itself in the public mind as the true embodiment “of a progressive nation’s character.”

Click image to view and download a 42.3-MB PDF of this 16-page booklet from the Chung collection.

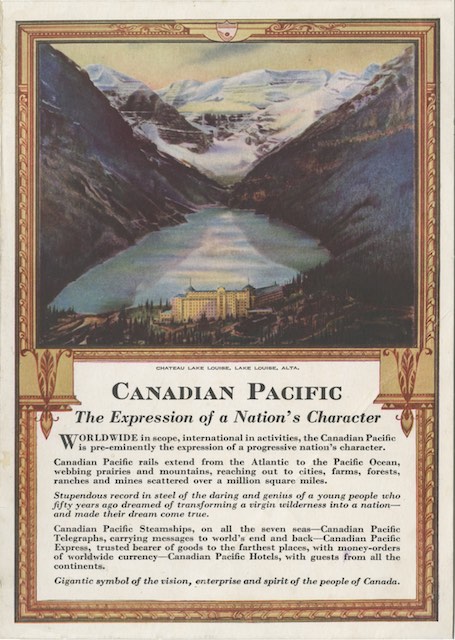

Click image to view and download a 42.3-MB PDF of this 16-page booklet from the Chung collection.

The backs of all of these booklets and menus have smaller images of CP’s dozen main lodges, chateaus, and hotels. The York is allotted a slightly larger image than any of the others, but most people wouldn’t notice the difference. Continue reading