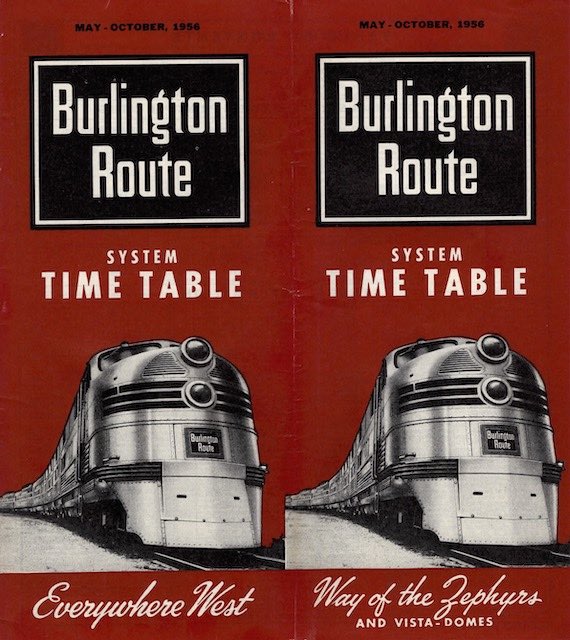

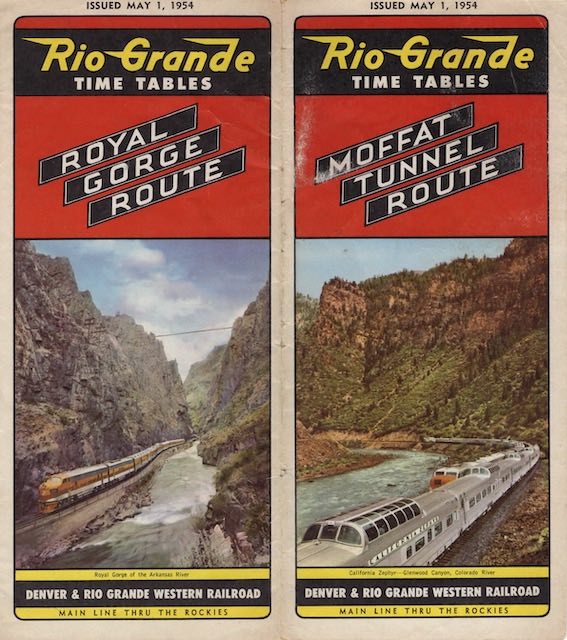

In addition to the color photos on the cover, this timetable makes some interesting if questionable uses of color. The inside front cover pictures two cars from the Prospector and one from the California Zephyr using black-and-white photos but with the Prospector cars colored in orange. Since stainless steel prints almost as grey anyway, this makes the photos look like they are in nearly full color.

Click image to download a 11.3-MB PDF of this timetable contributed by Ellery Goode.

Click image to download a 11.3-MB PDF of this timetable contributed by Ellery Goode.

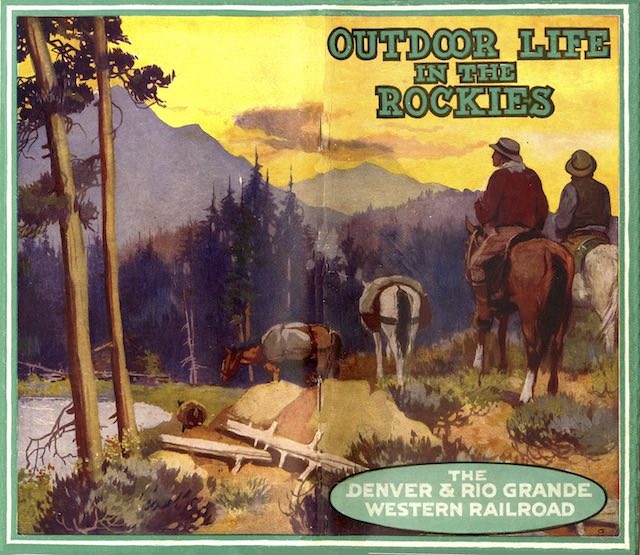

The back cover has an ad for Rio Grande vista-domes picturing the Prospector train and the Colorado Eagle, which went on Rio Grande rails between Pueblo and Denver. The photos are in black-and-white, but a Rio Grande “Main Line Through the Rockies” logo is in yellow and cyan. Continue reading