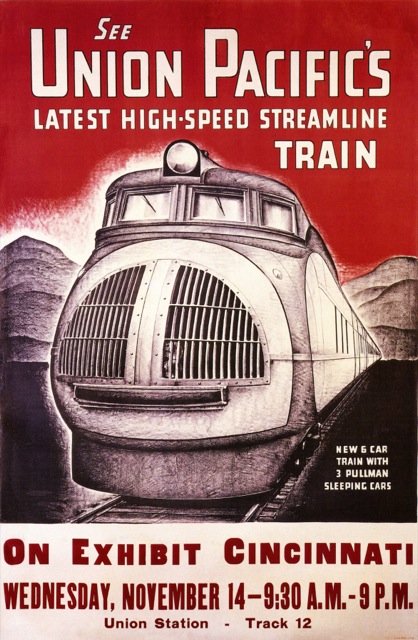

The Union Pacific was so confident about the success of the M-10000 that it ordered three more similar, but longer, trains even before the M-10000 was completed. Though the power cars of these trains were outwardly identical to the M-10000, with “turrent-style” cabs, the M-10001 was initially equipped with a 900-HP Diesel instead of the M-10000’s 600-HP distillate engine.

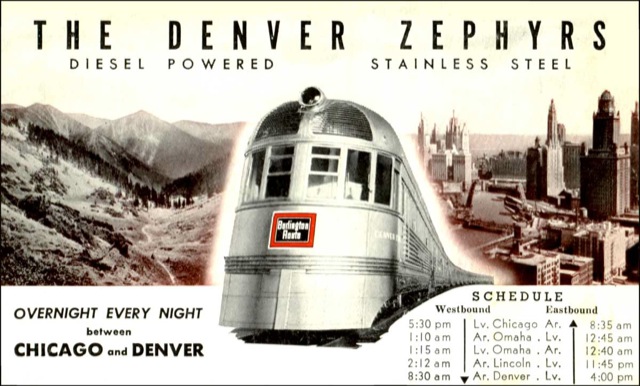

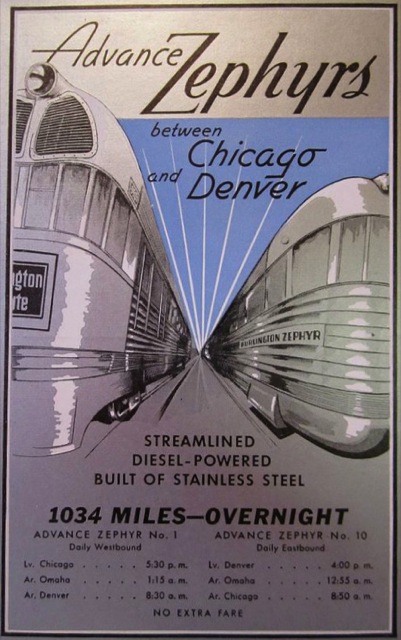

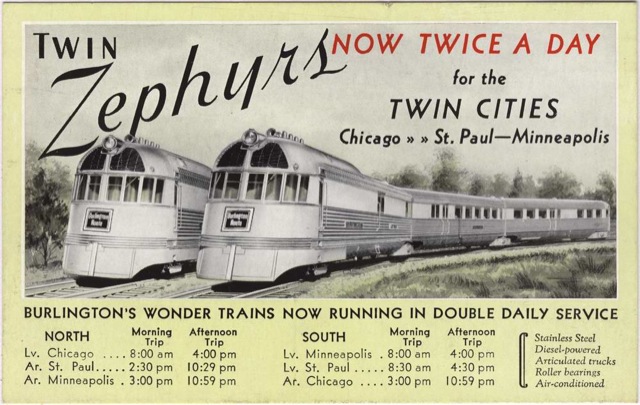

After receiving the M-10001 in the fall of 1934, the Union Pacific sent it from Los Angeles to New York in under 57 hours, a record that stands today. The train’s average speed over this route, however, was just 57 mph, compared with the Zephyr’s 77-mph run from Denver to Chicago and later the Denver Zephyr’s 83-mph run from Chicago to Denver (which, Ralph Budd pointed out, was uphill).

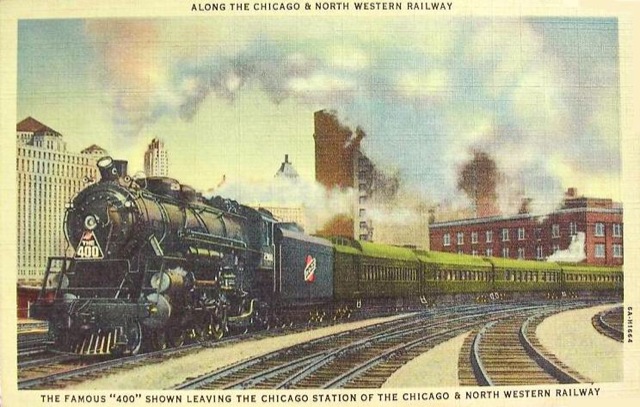

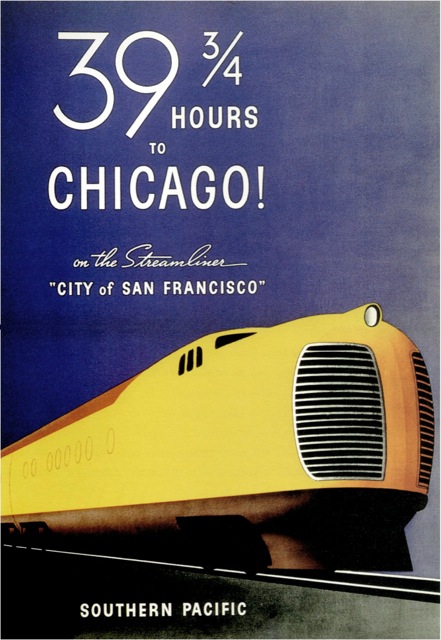

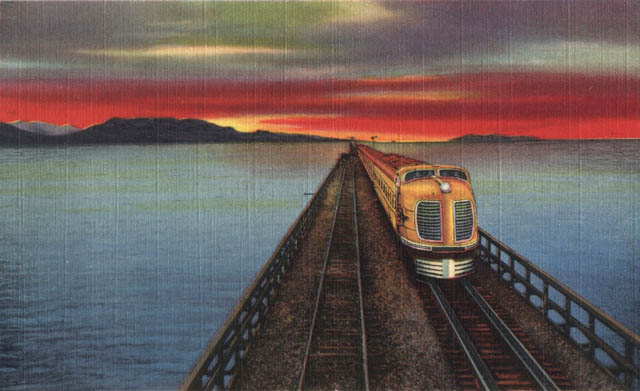

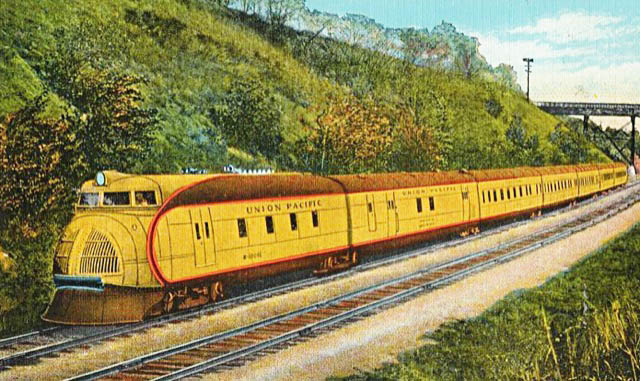

So before putting the M-10001 in revenue service, Union Pacific replaced its 900-HP engine with a massive, V-16, 1,200-HP Diesel. It then put the train to work as the City of Portland, running between Chicago and Omaha on the Chicago & North Western and from Omaha to Portland on the Union Pacific, taking 39-3/4 hours each way. Considering that previous trains took between 54 and 72 hours, this was an incredible schedule. A Chicagoan going to Seattle would have to change trains in Portland and would still arrive in Seattle nearly 20 hours sooner than if they took the Empire Builder, North Coast Limited, or Olympian.

Continue reading →