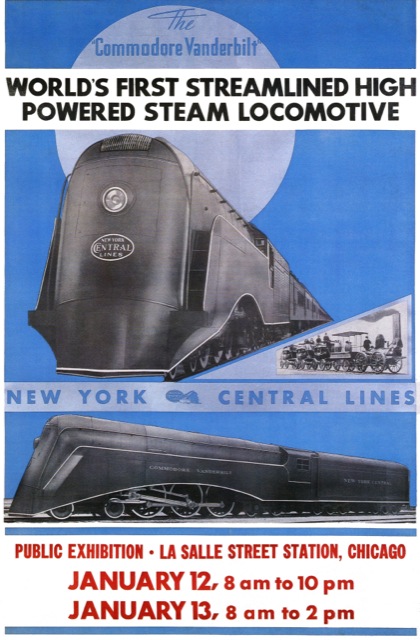

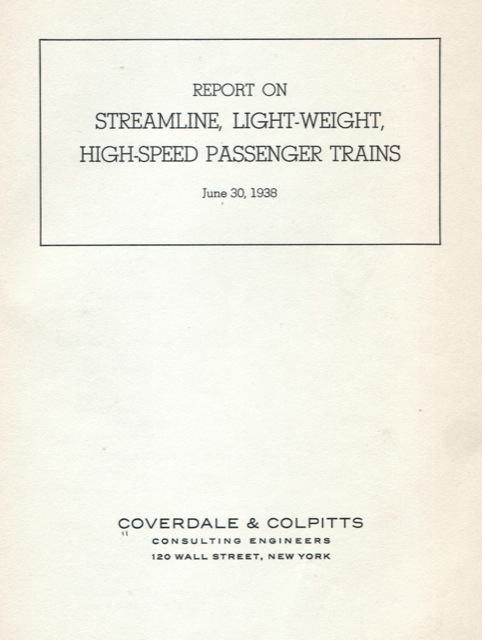

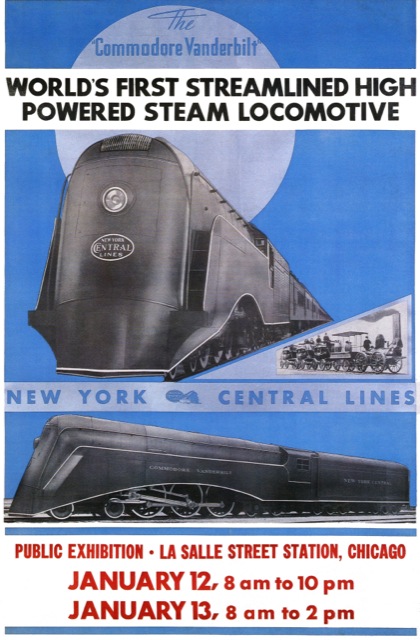

Out of the 120,000 or so steam locomotives built and used in the United States, only about 220 were streamlined–or, as the Chicago & North Western called it, steamlined–for passenger service. Railroads went to the trouble to streamline steam locomotives for three reasons.

First, some railroads, such as the Burlington, wanted steam locomotives as a back up in case the Diesels that were powering most of their streamliners broke down.

Second, many railroads, such as the Milwaukee Road, didn’t believe Diesels were powerful enough to reliably pull a full-sized train, and travel demand in their markets required more than the little three- and four-car streamliners pioneered by Union Pacific and Burlington. The Santa Fe proved Diesels could pull a full-sized train in 1937, but some railroads stuck with tried-and-true steam technology for as much as a decade after that.

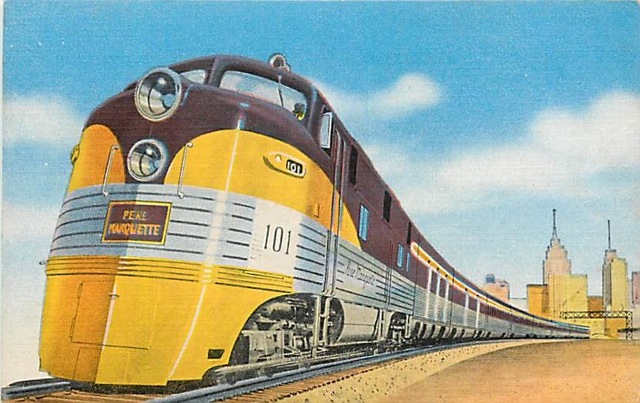

Third, some railroads decided it would far less expensive to put a shroud on an old steamer, making it look fast and new, than to buy new, expensive, and uncertain Diesels. Even the Union Pacific operated a supposedly streamlined (but actually mostly heavyweight) train with shrouded steam locomotives, counting the train among its fleet of streamliners.

Warning: This is a long post with more than two dozen pictures and may take some time to load. Clicking on most images will bring up a larger version–in some cases, particularly the posters, much larger. It is also unusual for this blog in that it doesn’t include any scans from my memorabilia collection.

Continue reading →