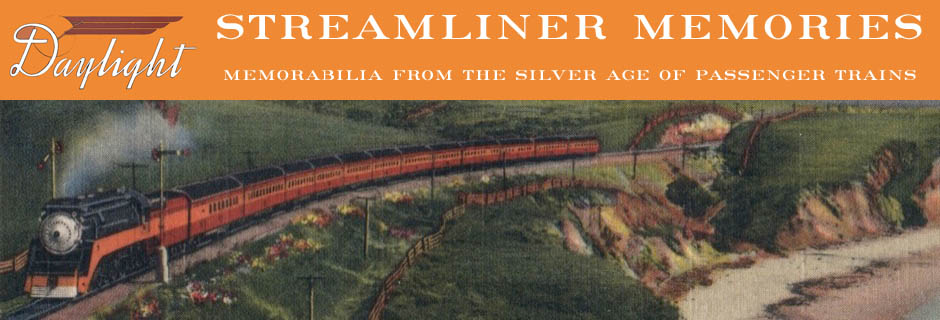

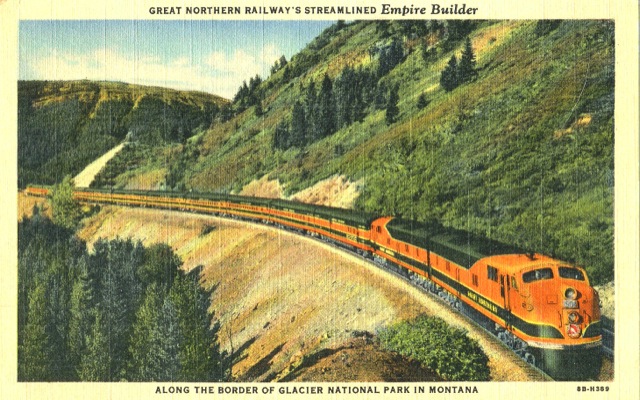

The first overnight streamliner after the war was the Great Northern Empire Builder, which started service on February 7, 1947. The train’s bright orange and green colors have come to be known as the Empire Builder color scheme, yet it was actually developed by General Motors for the Great Northern’s first Diesel freight locomotives, which the GN purchased in 1941.

Click to download a PDF of this postcard.

The goal was not to have an award-winning color scheme for passenger trains but to maximize safety and visibility. Orange happens to be the most visible color of the spectrum in a wide variety of weather conditions, which is why it played a prominent role in the streamlined colors of so many railroads: Milwaukee Road, Rio Grande, Southern Pacific Daylights, and Western Pacific, to name a few. For even more visibility, the green and orange stripes were separated by thin gold (later Scotchlite) bands, and the lowest stripe of each carbody was a thin, silvery-white band.

The green in the Empire Builder colors is, simply, Pullman green, a green so dark it is almost black; a green so bland that UPS (which in 1916 deliberately imitated Pullman’s colors in an attempt to borrow Pullman’s prestige) calls it brown (some say UPS/Pullman brown is different from the Pullman green that became ubiquitous in the 1920s and 1930s; I’m not convinced: at least some UPS trucks look green to me). Most hand-colored postcards, such as the ones shown here, use a brighter green than was really on the trains. See the Great Northern Railway Historical Society’s color page for reference colors (though I am dubious about their representation of the gold stripes that separated the green and orange).

Click to download a PDF of this postcard.

I’ve never particularly liked orange, and Pullman green is boring. Yet I feel a thrill whenever I see them together. It isn’t just me: readers of Passenger Train Journal once voted the Empire Builder their second-favorite color scheme after the Santa Fe warbonnets.

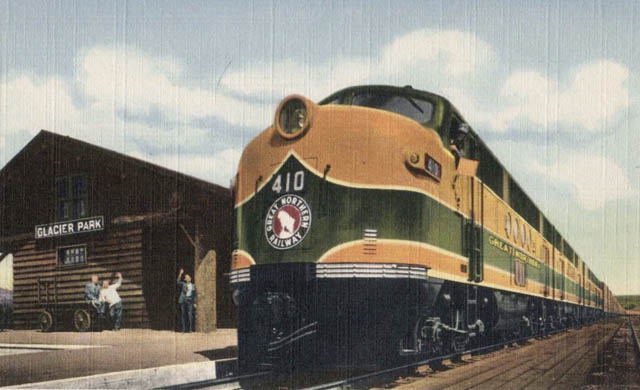

The first streamlined Empire Builders were twelve-car trains led by two 2,000-HP E7 Diesels. When delivered by General Motors, nearly two years before the rest of the trains, the fronts of the Diesels looked quite different from the freight Diesels the company painted in 1941. The upper green terminated on the roof of the locomotive, instead of covering the cab, while the lower green stripe terminated on the sides in red, forward-facing GN goats, sans the “Great Northern Railway” lettering. The very front of the locomotives had the words “The Great Northern” in gold script.

The Great Northern either decided this was too radical or too difficult to maintain. By the time the new Empire Builder trains were ready to go, GN had painted over the side goat logos and script and put a standard goat, surrounded by “Great Northern Railway,” on the nose. The vast expanse of orange still made the locomotives more visible at crossings than the freight scheme, though GN would adopt the freight scheme when it later used F locomotives to pull the Empire Builder.

Click to download a 3.2-MB PDF of this brochure.

As described in this brochure, the twelve cars included a baggage-mail car, a 60-seat coach (for passengers going short distances), three 48-seat coaches, a coffee-shop car, a dining car, four sleepers, and an observation-lounge car that also included three sleeping rooms. That allowed for a total capacity of just over 300 people. Due to high demand, the railway added two more sleeping cars to each train later in 1950.

The Empire Builder was one of the rare streamlined trains in which each car was prominently lettered with its own name. All lettering was in a unique Empire Builder font designed especially for the train. Sleeping, dining, and lounge cars all had unique names: lakes for the diners and coffee-shop cars; rivers for the observations cars; and passes and glaciers in Glacier Park for the sleeping cars.

Since the Empire Builder used the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy between St. Paul and Chicago, the CB&Q owned one of the five trains with the other four owned by the GN, and the name of the owner railway was painted in small letters at the ends of each car.

Despite its close association with the CB&Q, the GN did not buy any passenger cars from Budd until 1955. Instead, GN purchased all of the cars for the 1947 train from Pullman, spending $7 million (about ten times that in today’s money) on all five sets of locomotives and trains. (The CB&Q used its own locomotives for the St. Paul-to-Chicago portion of the trip.)

The Empire Builder didn’t try to match the Union Pacific’s 39-3/4-hour schedules. Instead, the Chicago-Seattle/Portland time was reduced from 59 hours to 45 hours. At least this matched or beat the time it would take a Union Pacific passenger to go from Chicago to Seattle, with a change of trains in Portland. The heavyweight equipment formerly used on the Empire Builder was bequeathed to a secondary train, the Oriental Limited, that ran on the same, 59-hour schedule as the old Empire Builder.

Unlike many other railroads, the GN had strict rules about its premiere train. No foreign cars were allowed to disrupt the consistent colors of the train. No business cars or other cars would be coupled behind the observation cars, obscuring the view of first-class passengers. The Empire Builder did not stop at Glacier Park (which would have resulted in nearly empty westbound summer trains west of Glacier); people going to Glacier and cars from other railroads carrying tour groups would go on the Oriental Limited.

To the annoyance of Great Northern officials, the Burlington didn’t always follow this policy on its portion of the Empire Builder’s run from Chicago to St. Paul. Instead, the CB&Q often added a stainless steel parlor car into the 12-car consist ahead of the Empire Builder‘s lounge observation in order to provide parlor space for first-class passengers between Chicago and St. Paul who did not want to pay for sleeping accommodations.