The Burlington not only had to compete with the Union Pacific in the Chicago-Denver market, it had two other entrenched rivals in the Chicago-Twin Cities corridor. The routes of both of the other railroads, the Chicago & North Western and Milwaukee Road, were shorter than the Burlington’s and also served Milwaukee, while the largest city on the Burlington route was LaCrosse. While the Zephyr was still on display at the Chicago fair, the other two roads introduced 90-minute, non-step service on the 85 miles between Chicago and Milwaukee on July 15, 1934 using conventional steam locomotives and heavyweight cars.

Tests by the Burlington showed that Zephyr streamliners could cut the time required for a Chicago-to-Twin Cities trip from 10-1/2 to around six hours. Both the Milwaukee and the C&NW elected to compete with the Twin Zephyrs using equally fast trains powered by steam locomotives. Achieving that time reduction with steam locomotives, which require frequent replenishments of water and fuel, required careful planning and advance preparation.

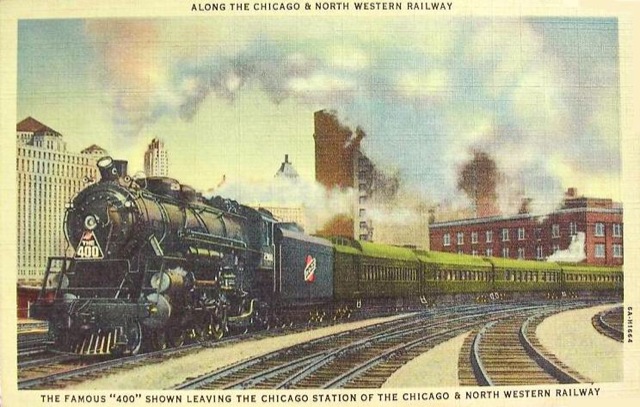

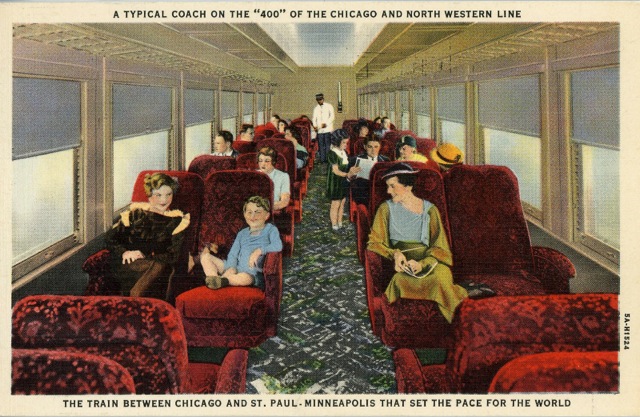

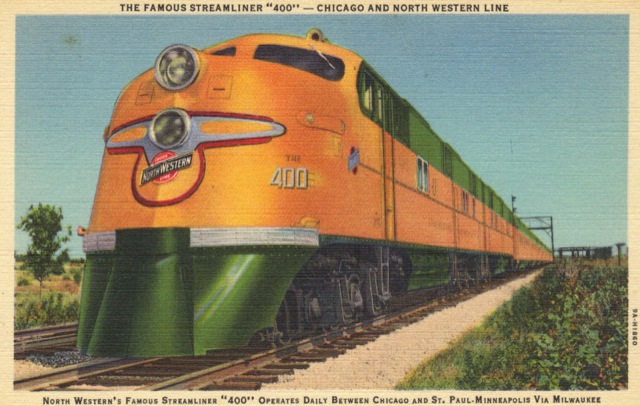

The C&NW was the first to speed its Chicago-Twin Cities service, starting on January 2, 1935. Reflecting the fact that Chicago and the Twin Cities were about 400 miles apart and the accelerated trip would take about 400 minutes, the railroad called its new train the 400. This was also a cultural reference to the fabled 400 families that supposedly made up New York high society. In fact, the train initially required seven hours–420 minutes–to go the 409 miles between Chicago and St. Paul.

Refurbished coaches included ice-activated air conditioning.

Contrary to the streamliner trend, the original 400 used conventional steam locomotives and refurbished heavyweight passenger cars. They achieved their fast average speeds by reaching top speeds of more than 90 mph. The railroad made track improvements to allow such fast speeds and converted some of its steam locomotives from coal to oil to reduce the need to stop for fuel. Rather than delay passengers for fuel and water stops, the railroad swapped locomotives at major stops.

The Burlington inaugurated Twin Zephyr service nearly four months later on April 25, 1935. But the initial four-car Twin Zephyrs had only 88 revenue seats and, because they were articulated, could not be easily expanded. So the 400s easily carried more passengers than the Zephyrs.

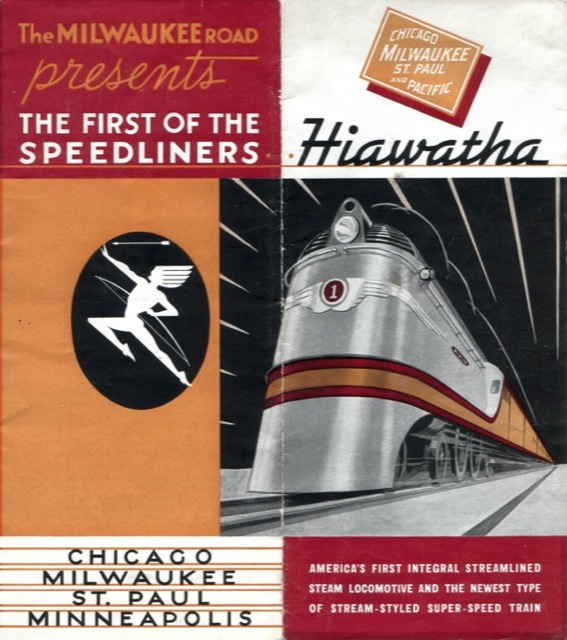

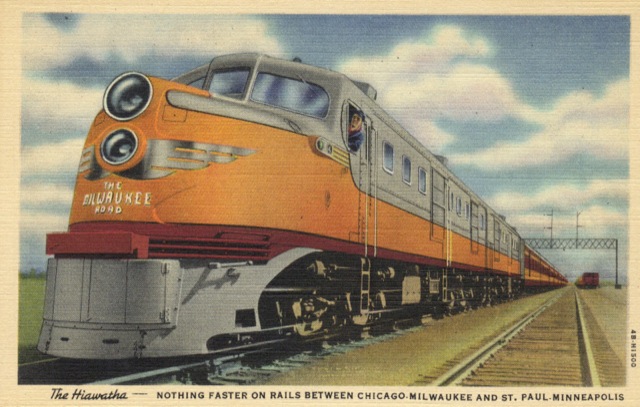

Despite coming late to the party, the Milwaukee Road outdid both the 400s and the Zephyrs. The railroad’s new Hiawathas began service on May 29, 1935. Like the Zephyrs, these trains were custom-built for the route. Like the 400s, they used steam locomotives, but locomotives unlike anyone had ever seen before.

Click the image to see a larger version; click here to download a PDF of the front and back of this postcard advertising the Milwaukee Hiawatha.

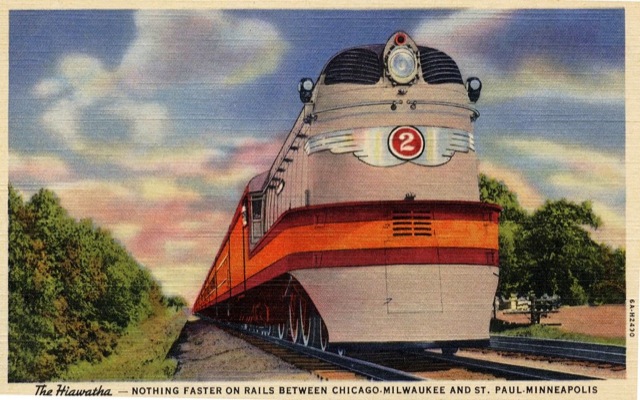

In the fall of 1934, the Milwaukee had ordered new 4-4-2 (four lead wheels, four driving wheels, and two trailing wheels) locomotives from the American Locomotive Works (Alco). Other railroads had converted existing steam locomotives into streamlined engines by putting shrouds on the outside; these were the first locomotives built from scratch.

Alco hired industrial designer Otto Kuhler to “stream styled” the new locomotives. While Kuhler is not as well known as Raymond Loewy, who designed Pennsylvania Railroad’s streamlined locos; Henry Dreyfus, who designed the streamlined locomotives for the New York Central’s 20th Century Limited; or Paul Cret, who helped Budd design the Zephyrs, Kuhler ended up streamlining more locomotives and passenger cars than Loewy, Dreyfus, and Cret combined.

The 4-4-2 was an unusual choice in an era when almost all passenger trains were powered by locomotives with six or eight driving wheels. Most steam locomotives have no gears, so the way to go faster at a given RPM is to increase the size of the wheels. Bigger wheels are more likely to slip, especially when starting, and more wheels mean more traction so less tendency to slip. On the other hand, more wheels mean more reciprocating parts, which means more vibration that can damage both the engine and tracks. The Milwaukee apparently reasoned that, at the speeds called for on the Hiawatha, fewer reciprocating parts were better than more traction.

Click to download a 4.4-MB PDF of this brochure.

Click to download a 4.4-MB PDF of this brochure.

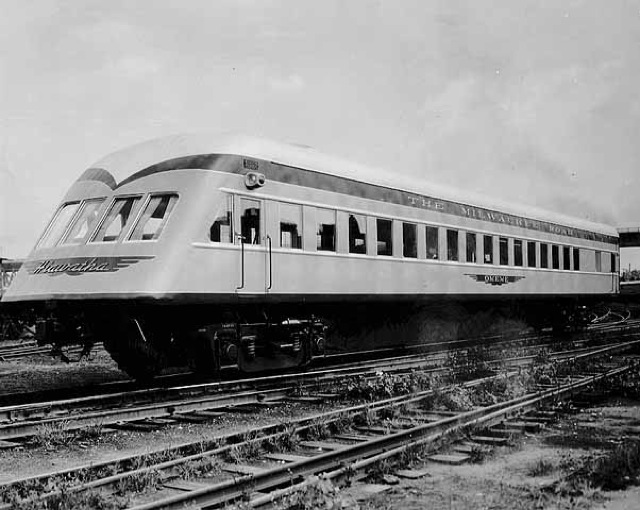

The cars themselves were built in the railroad’s own shops. The Milwaukee was one of the few railroads that did not contract with Pullman to operate its sleeping cars, and it believed it could build its own cars for less than it would cost to buy them from Pullman or another manufacturer. The cars were full-sized instead of the smaller profiles of the Zephyrs and early City trains, and one reason the railroad used steam to pull them is that it believed Diesels were not yet powerful enough to haul a full-sized train at 100 miles per hour or more .

The beaver tail observation car on the first Hiawatha had fairly small rear-facing windows.

The initial trains consisted of a bar car called the Tip-Tap Club, three coaches, a parlor car, and a parlor-observation car designed with a unique end that became known as a beaver tail. The locomotives and cars were painted orange with a maroon stripes. As demand increase, the railroad added more coaches, eventually running nine-car trains with no loss in speed.

The windows on the 1937 beaver tail observation car were much larger.

The Milwaukee made extensive track improvements to allow the train to operate at high speeds. For example, the outside rail of many curves was raised to be 3-1/2 inches higher than the inside rail so the trains could go around the curves without tipping. As a result, the train could safely negotiate many curves at 100 mph, and often reached 110 mph on its journey from Chicago to the Twin Cities.

Though streamlined in every sense of the word, the Milwaukee called its new trains “speedliners.” (It also called the locomotives “Milwaukee” types even though everyone else called 4-4-2 locomotives “Atlantics.”)

The 1939 beaver tail observation cars, whose design was refined by Otto Kuhler.

Partly because of the new design, the Hiawathas attracted more riders than the 400s. The Zephyrs did better after the new, seven-car trains were introduced in December, 1936, but the Hiawathas probably continued to be the top carrier, partly due to serving a higher population corridor and partly because of having trains of higher capacity–the Twin Zephyrs could hold 222 people, while the Hiawathas could carry more than 260.

Less than two years later, the Milwaukee completely reequipped the Hiawatha with new cars built in its own shops with a distinctive ribbed pattern on the sides. The beaver tail observation cars were refined from the original models. The new trains consisted of the Tip-Tap bar, four coaches, a diner, and three parlor cars.

In 1939, the train was completely reequipped again, this time led by new Alco locomotives. Styled again by Otto Kuhler, they were of the Hudson (4-6-4) wheel pattern and were capable of going 125 mph. With these more powerful locomotives, the Hiawatha could be expanded to as many as 15 cars, allowing the Milwaukee Road to carry far more people than the Zephyrs.

By 1939, the competitors had reduced the time between Chicago and St. Paul to 6-1/4 hours, with one of the Twin Zephyrs doing the trip in 6 hours. To meet this schedule, the Milwaukee shortened the time between Portage and Sparta, Wisconsin–78.3 miles apart–to 58 minutes, for a start-to-stop average speed of 81 mph. The Hudsons easily met this timetable.

In 1939, the C&NW received its first fully streamlined train, powered by E3 locomotives. Like the Santa Fe E1 and City E2, the E3s had two 1,000-HP Diesels, but the E3s used a new “567” model (for 567 cubic inches of displacement) that was one of the most successful railroad engines ever designed. Pullman manufactured the cars, including a lunch-counter/bar car, four coaches, a diner, three parlor cars, and a parlor observation car, for a total of 292 revenue seats.

Click to download a larger version of this postcard showing the Alco locomotives used to pull the Hiawatha starting in late 1941.

The Milwaukee finally purchased Diesels for Hiawatha service in 1941. These included two General Motors E6s–similar to C&NW’s E3s–and two Alco Diesels styled by Otto Kuhler. Kuhler’s Diesel design was arguably not as attractive as his steam designs, and Alco Diesels may not have been as successful as the company’s steam locomotives; for whatever reason, Milwaukee bought all of its future passenger Diesels from other manufacturers.

With top speeds around 105 mph, the Diesels could not go quite as fast as the steam locomotives, but they made up for it in greater performance ratios. Unlike steam locomotives, the Diesels did not need to be changed out in the course of a 400- (or even 1,000-) mile trip. At the end of a trip, when a steam locomotive might need hours of servicing, the Diesel was ready to go out on another trip. Diesels were also more fuel efficient, requiring less fuel to pull one ton one mile than an external-combustion locomotive. It was these characteristics that led to the Diesel revolution.

Raymond Loewy

Randal, if you are going to mention Mr. Loewy, I think one of his greatest creations should also get a nod – the PRR’s incomparable (and streamlined) GG1 electric locomotive:

Image of a GG1 with Mr. Loewy is here.

It’s baffling to see how the Milwaukee Road went through several generations of rolling stock within just a few years (what did they do with the old equipment, given that the lifetime of rolling stock back then was at least 30 years, as it is still today?)

That they went with steam is understandable, as at that time all maintenance infrastructure was focused on steam and there was no experience with long distance diesel operation. So the skepticism is understandable. Here in Europe the first diesel applications in the 1930s were small shunters, branch line units and most noteworthy a few express units which allowed to shorten travel times considerably, but had much less capacity than the steam trains that continued to dominate the network. Only in the 1950s this started to change on a larger scale (the Swiss railways were an exception, electrifying much of their network early, while electrified lines remained an exception in most other countries).

As new equipment was added to the Twin Cities Hiawatha, the Milwaukee Road moved the older steam engines and passenger cars to lesser Hiawatha trains, including the Midwest Hiawatha, the Chippewa Hiawatha, and the Northwoods Hiawatha. After dieselization, the early locomotives would, by 1948, move to replace the steamers on the lesser trains. 1948 would also mark the end of the beavertail lounge cars on the Twin Cities when the four Skytop Lounge cars were introduced.