Using pocketwatches–uncommon today but a sign of a railroader in the 1950s–as illustrations, the March 1953 ad emphasized the fact that the CZ was timed for scenery. Click any image for a larger view.

Fifteen of the California Zephyr ads I’ve found in National Geographic were cartoon ads. All were placed by Western Pacific, and in most cases the cartoons were drawn by Gerhardt Hurt, about whom little is known other than that he lived in San Francisco and illustrated at least one children’s book titled Scare Boy.

This 1950 cartoon ad from the New Yorker is signed (at the bottom of the top cartoon) “gh” for Gerhardt Hurt. This was also the only cartoon ad I’ve found that was signed by all three railroads and not just the Western Pacific. Click any image for a larger view.

The first cartoon ad I’ve found appeared not in Nat Geo but the New Yorker in 1950. It focused on the health of long-distance passenger rail travel in the face of airline competition. I’ve also found cartoon ads in the New Yorker and other publications that differed from any in the National Geographic series, and Hurt also did at least one cartoon ad promoting Western Pacific freight service.

The California Zephyr was, according to numerous advertisements, “the most talked about train in the country.” One or two ads even claimed that it was “the best-loved train in the country.” We can’t verify these claims today, but we can say that it was probably the best-advertised train in the country, at least as far as magazine ads go.

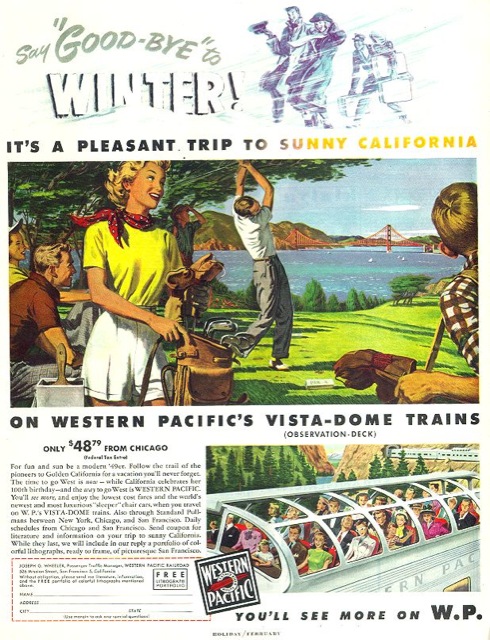

The first National Geographic ad for the California Zephyr didn’t even mention the Zephyr by name, instead just referring to “Western Pacific’s Vista-Dome Trains.” The ad was in the February 1949 issue, and the Zephyr would not make its inaugural run until March 20, 1949. In the meantime, the Burlington-Rio Grande-Western Pacific Exposition Flyer incorporated vista domes and other CZ cars as they arrived from Budd. While the smaller illustration in this ad shows the vista domes in the Feather River Canyon, the larger one focuses on the Lincoln Park Golf Course in San Francisco. Click any image to download a larger version.

Between February 1949 and February 1965, I’ve found nearly 40 full-page ads in National Geographic, as well as many more in Saturday Evening Post, Life, Holiday, and several other magazines. By comparison, I count only a handful of ads for the City of Los Angeles, Super Chief, or other major trains of the day.

The round-tailed observation car of the California Zephyr was supposed to be the pièce de résistance. In some respects, the car was magnificent. In others, it was surprisingly plain.

As shown in the cutaway diagram on the brochure below, which dates from before the train’s inaugural run, the car include three distinct non-revenue spaces–the observation room behind the dome, a lounge beneath the dome, and the dome itself–as well as three bedrooms and a drawing room that featured what may have been the only shower on a streamlined train in the West.

Click image to download a 2.1-MB PDF of this small brochure advertising the California Zephyr.

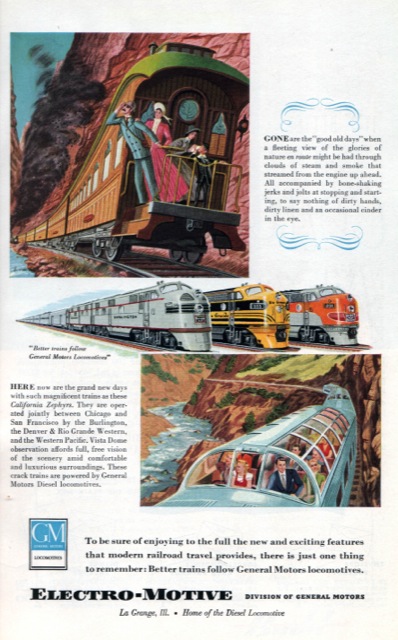

When the California Zephyr began operating, General Motors ran this ad saying that all three participating railroads had selected EMD locomotives to pull the train. But that wasn’t quite true.

This ad appeared in the July, 1949 issue of National Geographic. Click image for a larger view.

The three railroads had calculated that they would need 4,500 horsepower to meet schedules with the planned 11-car (but sometimes longer) train. Two 2,000-HP E7 locomotives wouldn’t do it, but three 1,500-HP F3 locomotives would. So the Burlington and Western Pacific each bought F3s, which turned out to be the only F-series engines that the Burlington ever used in passenger service. (Even so, the Burlington sometimes used two E units to pull the California train.)

I have two menus from the Cable Car Room, both dated 1969. One dated June includes four simple meals: beef stew; baked ham; turkey sandwich; and a fruit plate, each accompanied by a salad, bread (potato in the case of the sandwich), beverage, and dessert. The a la carte side includes two soups, eight sandwiches, four salads, and seven desserts. The menu also offers several beverages, candy bars, cigars and cigarettes (where allowed by law), and souvenir playing cards.

Click image to download a PDF of the June 1969 menu. Click here to download a PDF of the October 1969 menu.

Second only to the observation car, the dome-buffet car was one of the most elaborate cars on the California Zephyr. In front of the dome–the short end of the car–were tables and seats for 19 people, plus two small restrooms. The photo below shows murals carved in linoleum by Pierre Bourdelle, who also did the murals at the steward’s station in the dining cars.

Click image for a larger view.

Under the dome was tables and chairs for six more people, plus one chair without a table, giving the lounge a total of 26 non-revenue seats. The rest of the space under the dome was used for a bar and small kitchen for making light meals such as sandwiches and soups.

The California Zephyrs each had a stewardess known as a Zephyrette who assisted mothers and children, made train announcements, and took reservations for the diner. As explained in the Zephyrette manual, there was a specific procedure for those reservations. Unusual for rail service, passengers had a choice of three different kinds of dinners in the diner.

While her seatmate looks on dubiously, a California Zephyr passenger receives a dining car reservation card from a Zephyrette. Click image for a larger view.

First, early dinners were offered for passengers who wanted to save a little money. Starting at 4:15 pm (except the first night on the westbound train, which left Chicago too late to have a 4:15 service) and repeated at 5:00 pm, the early dinner offered limited selection but a full-meal price of just $1.10 (in 1950), compared with $1.65 (for ham and eggs) to nearly $4 (for a tenderloin steak) at the later seatings.

In about 1980, Passenger Train Journal called the California Zephyr “the classic train of our time” even though the Chicago-Oakland train had stopped running a decade before. What made the CZ special was that, as one ad said, it was the first transcontinental train “designed and timed [more] for sightseeing” than for getting from one place to another. While only the third train to have dome cars, it was the first to travel through scenery that truly deserved dome cars.

When the California Zephyr began running in 1949, the City of San Francisco was still on a 39-3/4-hour schedule aimed at attracting business travelers. The California Zephyr required 10-1/2 hours more, so rather than compete with the City on time, the Cal Zephyr competed on scenery: it was timed so that passengers could see the best scenery in Colorado, Utah, and California in daylight, while they slept through the relatively boring parts across Nevada and the Great Plains. The domeless City train, by comparison, crossed relatively desolate southern Wyoming during daylight hours and went over the scenic Sierra Nevada at night.

Click image to download a 2.0-MB PDF of this 20-page brochure.

Click image to download a 2.0-MB PDF of this 20-page brochure.

After the Twin Zephyrs and the Colorado Eagle, the next great–some would say the greatest–domeliner to hit the rails was the California Zephyr. This train followed the route of the Exposition Flyer, a train that began running in 1939, the year of the Golden Gate International Exposition, after which the train was named.

The Flyer was operated by three railroads: the Burlington from Chicago to Denver; the Denver & Rio Grande Western from Denver to Salt Lake City; and the Western Pacific from Salt Lake City to Oakland. The Rio Grande and Western Pacific had a shared history, as the latter was financed and built by the former when it was under the control of George Gould.

Click image to download a 5.0-MB PDF of this brochure advertising the Exposition Flyer and announcing the California Zephyr.