After the Great War, Canadian Pacific Ocean Services’ first priority was to add to its empress fleet in Atlantic service. First, it renamed the Alsatian, a ship of its recently acquired Allan Line, the Empress of France. The largest of the Allan Line ships, it was comparable in size to the Empress of Britain. After being completely refitted to bring it up to empress standards, the ship started its maiden voyage under its new name on April 4, 1919.

The 1914 Alsatian was acquired by CP which renamed it the Empress of France in 1919. This photo must be from the late 1920s when CP began painting its hulls white instead of the more traditional black, leading it to advertise its ships as “white empresses.” Click image to download a 138-KB PDF of this postcard.

Next, in 1921, it acquired three German ocean liners that had been taken by the British government as a part of war reparations. First was the 590-foot Prinz Friedrich Wilhelm, which CP operated as the Empress of India for just three round trips across the Atlantic before making it a monoclass ship and renaming it the Montlaurier.

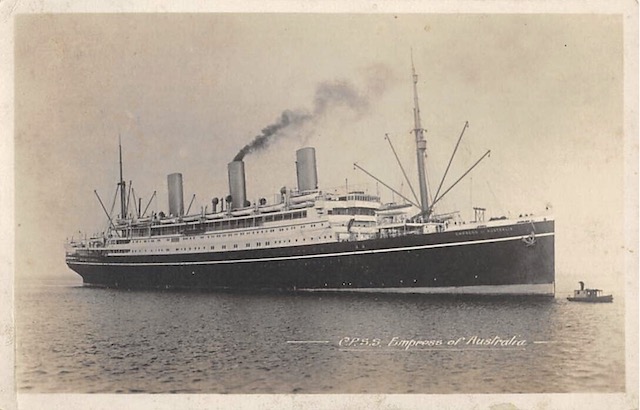

The Empress of Australia was the most successful of the former German ships that became empresses as it served Canadian Pacific up to the beginning of World War II and then served the British Admiralty until 1952. In contrast, the Empress of India was scrapped in 1929 and the Empress of Scotland in 1931. Click image to download a 138-KB PDF of this postcard.

Second was the 615-foot-long Tirpitz, which CP initially called the Empress of China but then renamed the Empress of Australia. It served the Pacific route from 1921 to 1923, then was transferred to the Atlantic route, where it served for many years. Third was the 677-foot Kaiserin Auguste Victoria, which CP renamed the Empress of Scotland. Serving the Atlantic route, this ship could carry nearly 1,900 passengers.

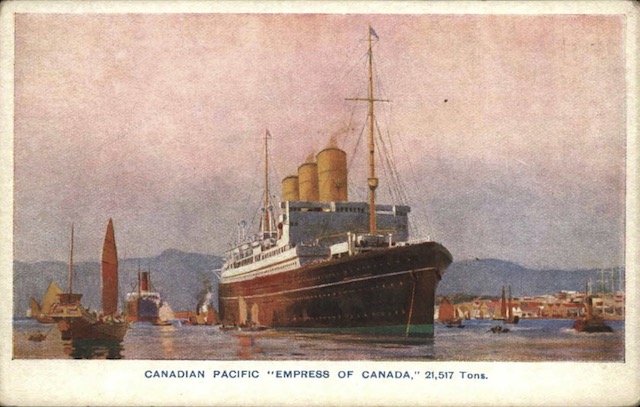

The 1922 Empress of Canada in an Asian port before its hull was painted white. Click image to download a 178-KB PDF of this postcard.

In 1922, CP replaced the Empress of India with a new ship, the Empress of Canada. Making its maiden Pacific route voyage on May 5, the 653-foot-long ship could carry more than 1,500 passengers. In about 1927, painted its ships’ hulls white instead of the more usual black, and began advertising them as “White Empresses.”

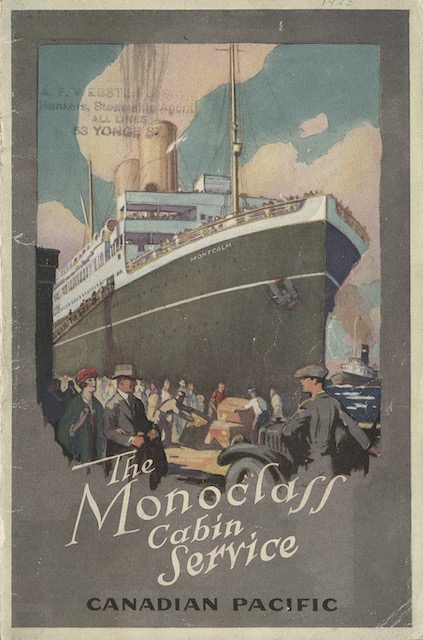

Canadian Pacific’s fleet of monoclass ships also increased, partly by the addition of the Allan Line. Former Allan Line ships that became CP monoclass ships included the Corsican, Scandinavian, Scotian, Tunisian, and Victorian. To these were added the Metagama, Melita, and Minnedosa, which had been ordered before the war, and Montcalm and Montrose, that had been ordered just after the war and went into service in 1922. In addition, the Empress of Britain, once the company’s flagship, was downgraded to a monoclass ship and renamed Montroyal in 1924.

Click image to view and download a PDF of this 1922 booklet about Monoclass ships from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

Click image to view and download a PDF of this 1922 booklet about Monoclass ships from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

Many of the Allan Line ships were aging. To replace them, in 1928 and 1929, Canadian Pacific added four ships to its Atlantic fleet in the duchess class, implying they weren’t quite as fine as the empresses but better than anything else. At around 600 feet long and configured for 1,570 passengers, the Duchess of Atholl, Duchess of Bedford, Duchess of Richmond, and Duchess of York had “cabin” and “tourist” classes.

The empress fleet typically served Quebec while the duchess fleet and other cabin-class ships served Halifax and St. Johns. But the St. Lawrence Seaway iced up in winters, so for five months of the year the empress ships and some duchess-class ships went on cruises to the Caribbean, Mediterranean, South America, or around the world while the lesser ships continued to ply the Atlantic route throughout the year.

Canadian Pacific’s next addition to the empress fleet was the 673-foot Empress of Japan, as the previous ship of that name had ended its service in 1923. The new ship, which made its maiden voyage in June, 1930, could carry nearly 1,200 passengers and make 22 knots.

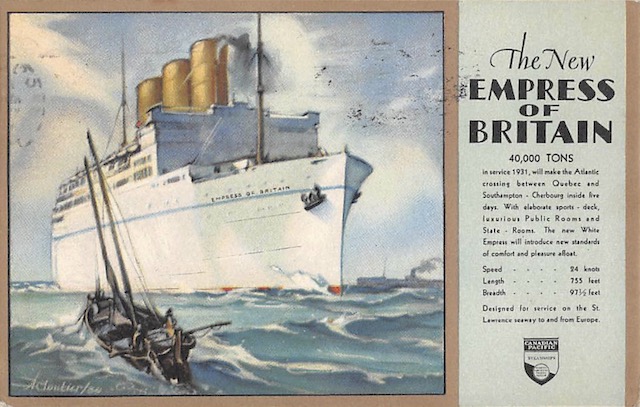

The longest, widest, and fastest ship in the history of CP’s empress fleet was the 1931 Empress of Britain, shown here in a painting by Albert Cloutier. Click image to download a 254-KB PDF of this postcard.

May 27, 1931, saw the maiden departure of the largest, fastest, and most magnificent ship in Canadian Pacific history, the Empress of Britain, replacing the Empress of Scotland. With a length of 760 feet, a beam of 98 feet, and capable of cruising at 24 knots, the ship was configured to carry fewer than 1,200 passengers compared with nearly 1,900 on the smaller Empress of Scotland. That’s because nearly 40 percent of them were in first-class cabins, the highest share of first-class passengers of any Canadian Pacific ship.

This was a recognition that large-scale immigration into Canada was slowing and so there was less demand for steerage or third-class travel. However, it may have been a miscalculation on CP’s part, or perhaps it was just the Depression, but the 1931 Empress of Britain turned out to be the least profitable of all CP ocean liners.

With the advent of World War II, the ships were all once again pressed into military service and the Empress of Japan was renamed the Empress of Scotland for obvious reasons. The empresses of Britain, Canada, and Asia were all sunk by enemy action along with the duchesses of Atholl and York and seven other Canadian Pacific ships. On top of that, after having survived both wars, the Empress of Russia caught fire while still in British admiralty hands in September 1945 and was scrapped. While the Empress of Australia survived the war, it was retained by the British admiralty for troop service.

We’ve seen this painting by Oswald Pennington before on a menu. This was originally a German ship that had been hastily purchased to replace the Empress of Canada when that ship sank in 1952. Click image to download a 206-KB PDF of this postcard.

The war reduced Canadian Pacific’s fleet to just five ships, two of which were freighters, so it scrambled to keep its Atlantic routes going. It upgraded the remaining two duchesses to empresses, the Duchess of Bedford becoming the Empress of France and the Duchess of Richmond becoming the Empress of Canada. The Empress of Scotland née Empress of Japan was also put to work on the Atlantic route, allowing for up to five sailings a month from Montreal or Quebec to Liverpool. When the Canada sank while in port in 1953, CP bought a German ship, the De Grasse, and renamed it the Empress of Australia.

Pacific empress service was but a memory, and the Canadian-Australiasian Line, which was half-owned by Canadian Pacific and half by Union Steamship of New Zealand, had only one ship left, the Aorangi. Before the war, the Aorangi and partner ship Niagara offered monthly service between Vancouver and Sydney, but the Niagara sank after hitting a German mine in 1940. This reduced service to six times a year and even that service depended on government subsidies of up to $250,000 a year (US$2 million in today’s dollar). When the subsidies ended in 1953, so did the service.

With all of the cabin-class ships gone, Canadian Pacific no longer offered world tours on its empresses in the winter. Though it still offered some shorter cruises, at least one empress worked year round between Canada and England, making port in Montreal or Quebec from mid-April to November and in St. John from December to early April when the seaway was likely to be iced up.

Business in the 1950s was good enough that Canadian Pacific ordered three more empresses. First, the Empress of Britain made its maiden voyage on April 20, 1956, and Empress of England followed on April 18, 1957. These sister ships were 640 feet long and had capacities of about 1,050 passengers. Having learned from the experience of the previous Empress of Britain, only 15 percent of the passengers were in first class.

In 1968, Canadian Pacific repainted its last ocean liner, the Empress of Canada, in a green CP livery with the “multimark” on the funnel Click image to download a 210-KB PDF of this postcard.

Finally, a new Empress of Canada made its maiden voyage on April 24, 1961. At 650 feet, it was slightly larger than the Britain and England, but its passenger capacity was about the same, using the extra room by devoting 19 percent of its passenger accommodations to first class.

All three of these ships were rated at 20 knots, quite a bit slower than the 24-knot Empress of Britain of 1931 and well short of the 35-knot SS United States and Cunard’s 32-knot Queen Elizabeth. However, the real competition wasn’t other steamship lines but jet airliners, which caused demand for trans-oceanic service to decline rapidly in the 1960s. The Empress of Britain made its last trip for Canadian Pacific in 1964 and was sold. The Empress of England lasted until 1969 and Empress of Canada two years more.

Over 85 years of Canadian Pacific ocean liner operations, 20 ships held an empress title, 13 of which were built as empresses and the others purchased from other steamship companies or upgraded from the duchess class. These ships played a key role in making Canadian Pacific “the world’s greatest travel system.”

Over the next two months, I plan to present dozens of booklets and menus that were used on empress ships, along with a few used in Canadian Pacific dining cars or hotels. Some will be from my own collection but most will be from the Chung collection. The empress menus from the Chung collection that I’ve shown in the past were ones that might also be found on dining cars, but all of the empress menus I’ll present in the next few weeks were exclusively designed for the steamships. Nevertheless, I hope you enjoy them.

Although Canadian Pacific’s shipping across the Pacific ended after the war (apart from the Aorangi), they did of course replace it with air service. Canadian Pacific Airlines began service from Vancouver to Tokyo-Hong Kong (via Shemya, Alaska) and Honolulu-Nadi-Sydney (via Canton Island) in 1949. They also famously retained the practice of naming their planes “Empresses,” which were also used in their radio callsigns.