In 1924, GN completely re-equipped the Oriental Limited with mostly all-steel cars. The new cars were such an improvement that for the next five years GN invariably called the train “the New Oriental Limited.” Among the amenities not found on the old Oriental Limited were a barber, ladies maid, and shower baths, all of which seemed to be required for a true limited train of that era.

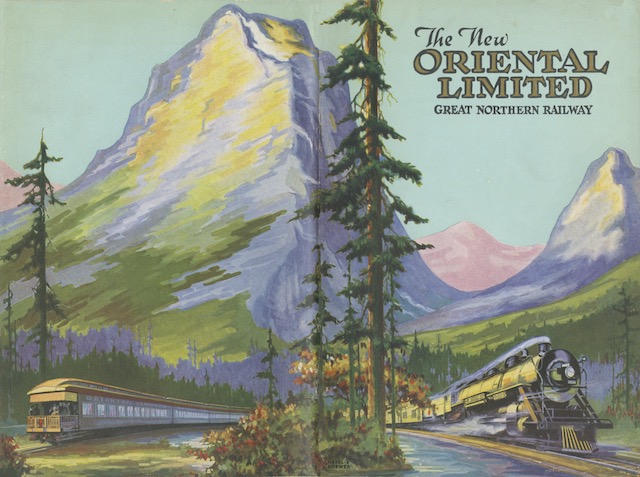

Click image to download a 6.9-MB PDF of this 30-page booklet. Click here to download a 6.2-MB PDF showing the wraparound cover of the booklet.

According to the May 31, 1924 issue of Railway Age, each of the eight trainsets consisted of:

- A baggage car with an dynamo to power the train’s electric lights;

- A smoking car (really a short-distance coach) that included four sections that made into berths at night for the use of the dining car crew but used as coach seats during the day;

- A first-class coach;

- A Pullman tourist sleeper with twelve sections, large washrooms, a barber shop, and men’s shower;

- A diner;

- Three Pullman sleepers with 12 sections and a drawing room; and

- A Pullman observation car with a buffet, smoking room, women’s lounge and shower, two compartments, a drawing room, and an observation parlor with extra tall windows and seats for 15 people plus room for eight on the rear platform.

It wasn’t quite an all-steel train as the smokers and tourist sleepers were remodeled from older, steel-sheathed cars. The other cars were all new and all steel, but the above booklet carefully calls it just “the new steel Oriental Limited.” The observation car can be distinguished from one on the old Oriental Limited as the latter had a giant plate-glass window looking out at the rear platform with a door on the side while the new observation car had a door to the platform in the middle and smaller windows on either side.

This 1924 booklet about the train emphasizes that it includes “Pullman Oriental sleeping cars.” That was a clue that the cars were not only manufactured by Pullman, they would be owned and operated by Pullman rather than by the GN as with the previous Oriental Limited. The September 20, 1924 edition of Railway Age reported that Great Northern and Pullman had agreed to have the latter take over sleeping car service on all other Great Northern trains by March 1, 1925. This left the St. Paul road as the last major railroad to still operate its own sleeping cars.

It’s a bit ironic that Ralph Budd was president of the Great Northern when the road decided to knuckle under to Pullman’s monopoly. About 15 years later, Budd was president of the Burlington Route when that road challenged Pullman’s monopoly because Pullman refused to operate cars manufactured by the Budd Company (no relation to Ralph Budd). This challenge led the federal government to break up Pullman into a manufacturing company and an operating company. Neither of these decisions would have been made without approval from the president.

Great Northern had the cars painted olive or Pullman green, but a light green was used on the name board. No one is sure what shade of green was used on the name board, but some speculate it was the same green used to paint some Great Northern steam locomotives. That’s not very helpful because no one is sure what shade of green was used on those locomotives. A former GN steam locomotive on display in Havre is painted green, but rumor has it that the city used green paint that it had on hand for painting its park benches.

The Oriental Limited was the only Northwest train to have its name painted on the name board, a practice that would later be continued for the Empire Builder. The name of the owner of each car (either Great Northern or Pullman) was in smaller letters on the end of each car.

Each trainset weighed almost 700 tons, not including passengers and baggage. To pull these trains, GN purchased 4-8-2 Mountain-type locomotives with nearly 55,000 pounds of tractive effort. GN’s first Mountain locos, which it acquired in 1914, produced nearly 62,000 pounds of tractive effort. But their small, 62″ driving wheels limited their speed, so in 1923 GN sacrificed power to get locomotives with 73″ wheels for its premiere train.

Unusually for the railroad, the 1923 locos did not have a Belpaire firebox that put a squarish bulge on top of the boiler. This reduced their efficiency a bit but greatly improved their appearance such that many people thought these were GN’s best-looking steam locomotives.

We’ve seen most of the black-and-white photos in this booklet in the form of colorized postcards that the Great Northern issued at the same time as the booklet. The booklet cover shows the Oriental Limited along the Skykomish River with Mount Index in the background. This must be a westbound train, as that would have passed this point in early afternoon while the eastbound train went by Mount Index at night.

The cover painting is signed Hazel E. Brewer. This refers to Hazel Eunice Brewer Wilson, an “artist who loved flowers, painting and her family.” She was born in Minnesota in 1896 — making her 27 years old when she did this painting — and lived to be 95 years old.

Hazel Brewer about the time of her marriage to Frederic Barlow Wilson in 1925.

Hazel Brewer about the time of her marriage to Frederic Barlow Wilson in 1925.

Like many artists, Brewer preferred to do fine artwork but commercial art helped pay the bills. She came from a family of artists: her uncle, Nicholas Brewer, was a famous landscape and portrait artist who was commissioned to do a portrait of Franklin Roosevelt. Brewer’s cousin (Nicholas’ son) Edward Brewer did commercial art for Cream of Wheat. Another of Nicholas’ sons, Adrian Brewer, moved from Minnesota to Arkansas where he started an art school and became of of the state’s best-known landscape painters.

Hazel Brewer herself did landscapes and portraits as well as commercial art for such companies as Red Wing Shoes. For a time in the 1920s, she had her own gallery and studio in Minneapolis. Later, she became head of the art department at Brown & Bigalow, which provided stock and custom art work for railroad advertising.