In 1905, the St. Paul Road (which is what people called the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul in the early 20th century) reported earnings of nearly $50 million against operating costs of $32 million, which made it one of the more profitable railroads in the country. In that year, the company’s board of directors decided to build a 1,374-mile extension to Seattle, which was estimated to cost $60 million.

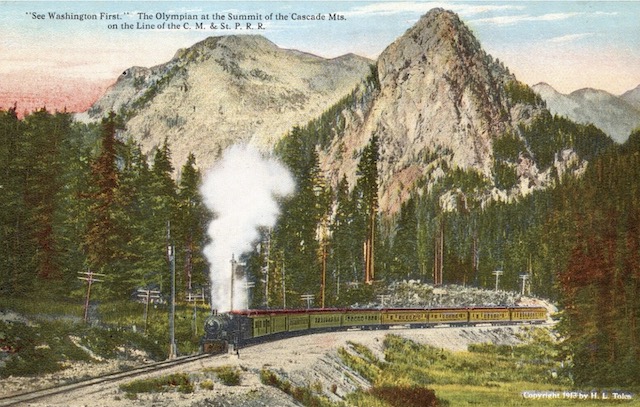

The Olympian was initially pulled by 4-6-2 Pacific locomotives. Click image to download a 253-KB PDF of this postcard.

By the time the railroad reached Seattle, on May 19, 1909, the project had cost $230 million, nearly four times the original projection. Like some other 20th century rail construction projects (such as the SP&S), the railroad got caught by an inflationary period in both construction and labor costs. On top of that, the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 greatly reduced the demand for transcontinental shipping. The St. Paul Road went bankrupt in 1925 and emerged as the Milwaukee Road in 1928.

Before going bankrupt, however, the St. Paul Road joined the competition for Northwest rail passengers. Initially, the railroad provided only a local service that took about 108 hours to get from Chicago to Seattle, with a notice in the Official Guide that this was “a continuous Local Service and not Through Service. Announcement will be made in due time of the inauguration of the through Transcontinental Service.”

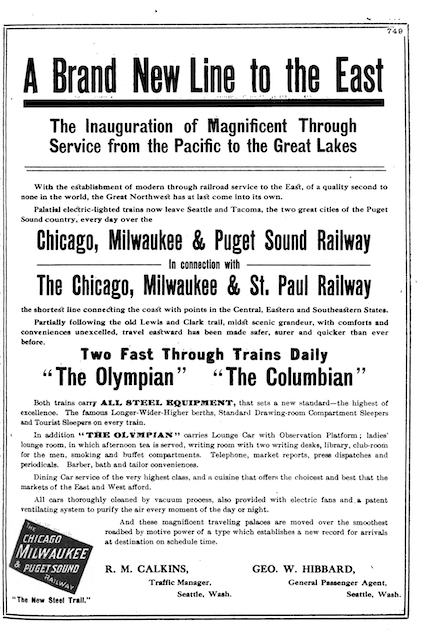

The St. Paul Road proudly announced “the inauguration of magnificent new service” in the January 1912 Official Railway Guide. Click image for a larger view.

The St. Paul Road proudly announced “the inauguration of magnificent new service” in the January 1912 Official Railway Guide. Click image for a larger view.

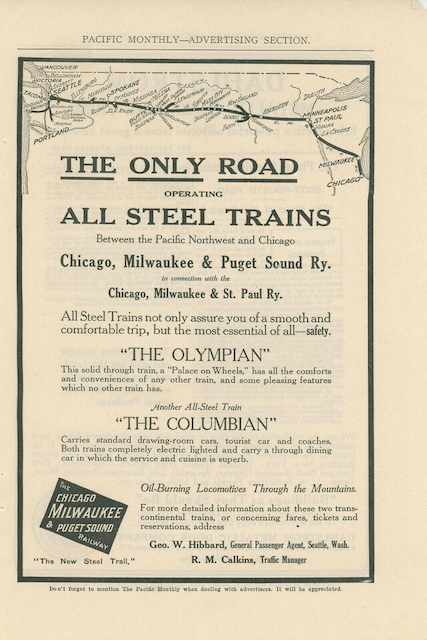

That inauguration came on May 28, 1911, and though that was more than two years after the line had opened, and 18 years after the most recent of its competitors began operating, the railroad clearly intended to make a statement. First, it began running not one but two limited trains, one named after the Olympic Mountains of northwest Washington and the other named after the Columbia River. Second, both were all-steel trains, immediately making every other train in the Northwest obsolete. As noted in an ad, steel not only provided “a smooth and comfortable trip, but the most essential of all–safety.”

Comfort and safety were the main advantages of all-steel trains according to this ad in a popular magazine. Click image for a larger view.

Comfort and safety were the main advantages of all-steel trains according to this ad in a popular magazine. Click image for a larger view.

In 1916, the St. Paul Road electrified its route over the Rocky Mountains. That saved the company enough money that, in 1920, it also electrified its route over the Cascade Mountains. Until 1916, however, the railroad relied on steam locomotives for the entire route.

Being so late in the game, it was able to skip the 4-4-0 and 4-6-0 stages and go directly with 4-6-2 Pacific-type locomotives. The St. Paul Road had a large number of Pacifics with 79″ drivers that typically produced about 32,000 pounds of tractive effort for its fast trains in the Midwest. For the mountains, however, it purchased some otherwise similar Pacifics but with 69″ drivers, boosting power to more than 36,000 pounds. The Pacifics were not delivered with superheaters, but the railroad soon added them.

The St. Paul Road advertised that its was “the shortest line connecting the Coast with points in the Central” states. Its Chicago-Seattle line was 2,182 miles, compared with Great Northern’s 2,245 and Northern Pacific’s 2,343 miles. However, the St. Paul trains weren’t necessarily any faster than the other trains.

The Olympian took 72 hours to get from Chicago to Seattle. This was not only exactly the same as the Oriental Limited (via the Burlington to St. Paul), both left Chicago and arrived in Seattle at the same times. The Columbian took 75-1/3 hours, while Great Northern’s Oregonian took only 73-1/2 (but required a change of trains in St. Paul).

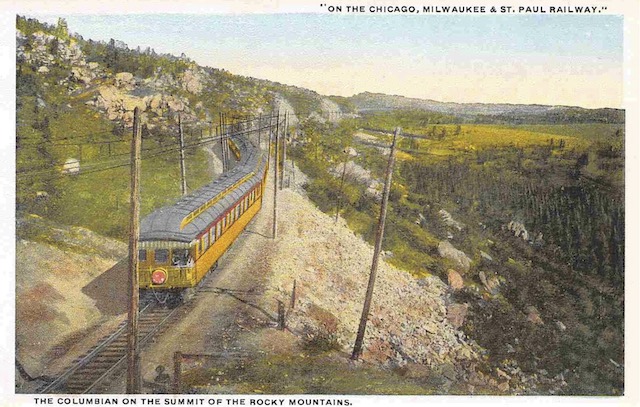

The Columbian, shown here after the Rocky Mountain segment was electrified in 1916, was not quite as fast as the Olympian and didn’t have quite as many amenities, but it was still a quality, all-steel train. Click image to download a 253-KB PDF of this postcard.

The North Coast Limited didn’t do quite as well, requiring 73-3/4 hours including a change of trains in St. Paul. That change of trains wouldn’t be necessary after December 17, when NP and C&NW began running the NCL through to Chicago, reducing travel time to 72-1/4 hours or 15 minutes more than GN or the St. Paul. NP’s secondary train, the Northern Pacific Express, took 75-3/4 hours.

For comparison, Union Pacific’s fastest train to Portland took 71-3/4 hours. The Oriental Limited connection to Portland via the recently completed Spokane, Portland & Seattle, was 15 minutes quicker.

Electrification cost the railroad at least $27 million, but it reduced operating costs and simplified operations in an era when steam locomotives demanded fuel, water, and constant tending. In the non-electrified portions of the route, the St. Paul Road continued to use Pacifics, graduating to Pacifics in the 1930s and Northerns in the 1940s.

Otto Perry took this photo of an unlikely combination: a 2-6-6-2 locomotive pulling the Olympian near Spokane, Washington in 1931. The locomotive had recently been rebuilt, replacing compound cylinders with simple ones and adding superheaters, pushing its power to 82,700 pounds of tractive effort. I suspect the railroad was testing the locomotive after its rebuild, as it usually would be dedicated to freight. Click image for a larger view.

Like the Great Northern, the Milwaukee Road terminated its secondary train, the Columbian, early in the Depression and then reinstated it in 1947 using the Olympian‘s old equipment when the latter was streamlined. The reinstated Columbian only lasted to 1955 and the streamlined Olympian Hiawatha saw its last run depart on May 22, 1961, almost exactly 60 years after the St. Paul Road introduced the technologically most advanced trains in the Pacific Northwest.