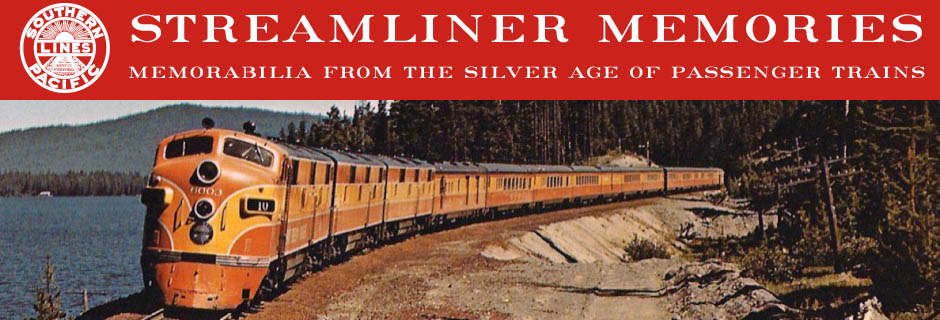

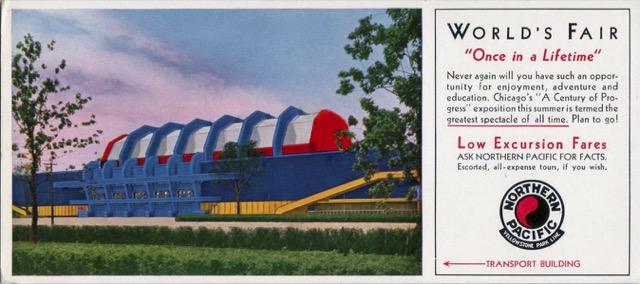

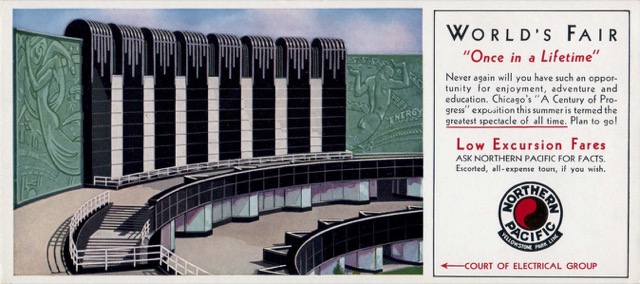

These blotters from the Dale Hastin collection reveal how colorful and fantastic the 1933 Chicago Century of Progress Exposition must have been. Instead of relying on classical architectural styles, as the 1893 Columbian Exposition had done, the planners of the 1933 fair wanted a more modern feel. Where the 1893 fair was known as the White City, the 1933 fair was called the Rainbow City, as most buildings were painted in four bright colors, with a total of 23 colors used. Most of the buildings were made of plywood, pressed board, and similar easily assembled (and easily disposed of) materials.

Click the image of any blotter to download a PDF of that blotter. Blotter PDFs average about 0.5-MB in size.

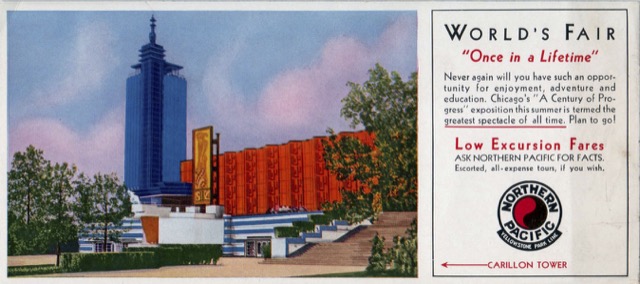

Yet the architectural styles used were not modern in the sense advocated by such architects as Mies Van der Rohe or Le Corbusier. Instead, it was more of an industrialized art deco style that was a perfect fit with the streamliners that would be introduced in the 1934 continuation of the fair. For example, Paul Cret, who would help design the Burlington Zephyr, also designed the Hall of Science shown on this blotter with its associated Carillon Tower.

This blotter shows only a part of the Transport building. The transport complex included separate buildings for Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler as well as a giant exhibit hall with a center dome held up by “sky hooks.” It is possible NP excluded these other buildings so as not to advertise its automotive competition.

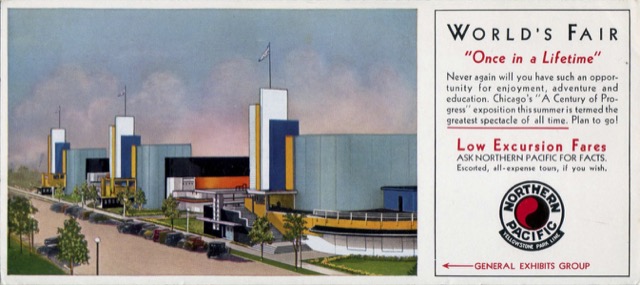

While the colors were exciting, the architecture was also, in a way, depressing as it emphasized the dehumanizing industrialization of the world that was then taking place. The ideas of Frank Lloyd Wright were specifically rejected by fair planners supposedly because he didn’t work well with others (which was true) but in reality because his vision was far more humanistic than the assembly line styles illustrated by the General Exhibit Building in the above blotter.

Designed by Raymond Hood, the Electrical Building is another example of industrial moderne as it looks like one of the large hydroelectric dams that were then the latest word in power production. While Wright was the model for hero-architect Howard Roark in Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, Hood is thought to have been the model for Rand’s anti-modern architect Peter Keating.

Since the fair was a celebration of the centennial of Chicago’s founding, it was natural to have a historic section including Chicago’s predecessor Fort Dearborn, which had originally been built in 1803.

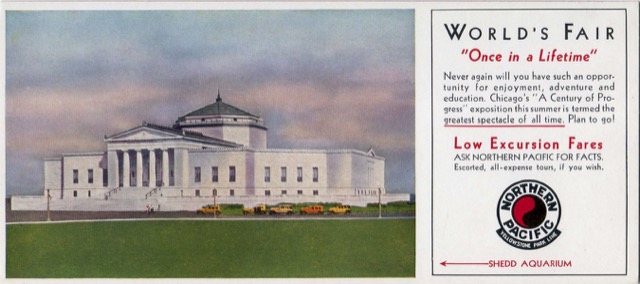

The Shedd Aquarium wasn’t really a part of the fair, having opened in 1930–which explains why it has a more classical appearance. However, it was immediately north of the fairgrounds, so many people who visited the fair also went to the aquarium. Unlike the fair buildings, the aquarium still exists today.