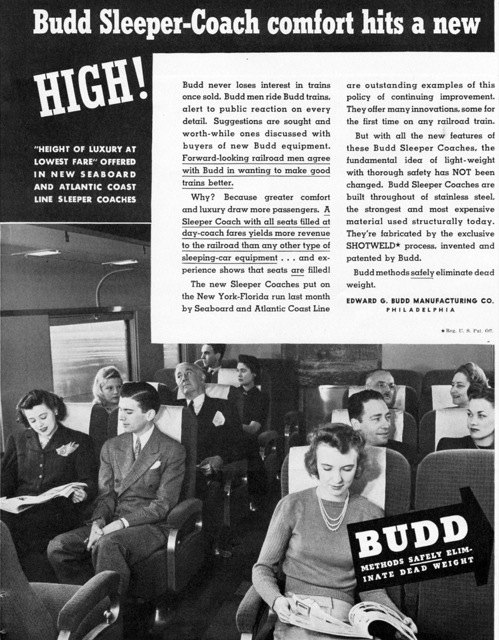

Although Seaboard Airline was the first to offer a New York-Florida streamliner, Atlantic Coast Line (ACL) was the larger and healthier of the two competitors–Seaboard had gone bankrupt in 1907 and again in 1930. ACL was initially skeptical about streamliners, saying they might make sense “out West” but not in the east where frequent stops negated the advantage of the trains’ faster top speeds. But after the success of the Silver Meteor, the railroad ordered its own Budd-built streamliners to compete.

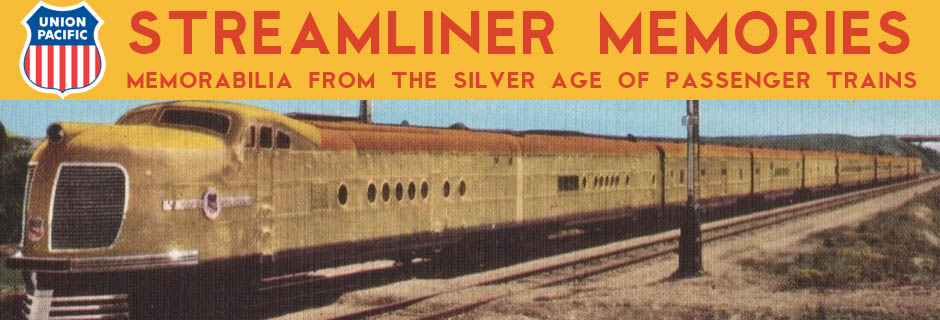

This postcard must be from 1941, as it mentions the west coast (Tampa) section of the Champion. Click image to download a PDF of this postcard.

The Champion went into daily service on December 1, 1939, ten months after the Silver Meteor began once-every-third-day service and the same day the Silver Meteor went daily. Unlike Seaboard, Atlantic Coast Line did not own its own tracks to Miami, so it relied on the Florida East Coast to bring its trains from Jacksonville down the east coast of the state.

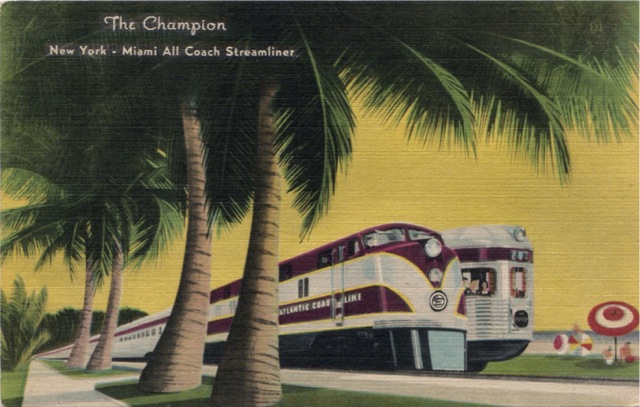

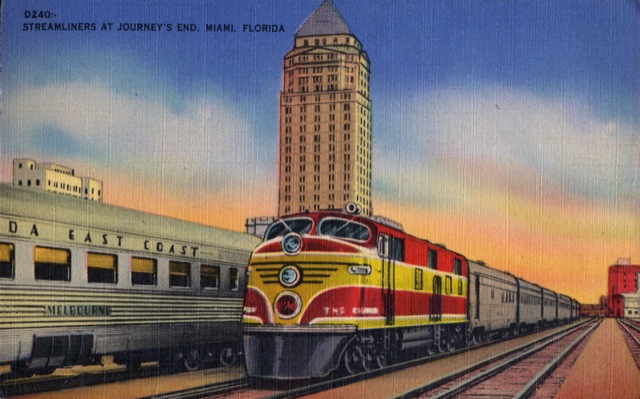

The Champion and Henry Flagler side-by-side in the Miami train station. “Melbourne” was a coach built for the Henry Flagler, so that train must be the one on the left. Click image for a larger view.

As a result, one of the three Champions required to provide daily service was owned by Florida East Coast while the other two were Atlantic Coast Line’s. (Although Pennsylvania and Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac operated the train north of Richmond, they didn’t contribute any equipment.) Atlantic Coast Line painted a purple stripe above the windows of its cars; Florida East Coast left its cars bare except for lettering.

A Budd advertisement in the January 4, 1941 Railway Age focuses on the coaches purchased by Seaboard and Atlantic Coast Line to supplement the original Silver Meteor and Champion all-coach trains. Click image to download a 0.8-MB PDF of this four-page ad.

Regardless of owner, all three trains were pulled by E-3 locomotives and consisted of a baggage-coach with 22 revenue seats; three 60-seat coaches; one 52-seat coaches that included a room for the stewardess; a 48-seat diner; and a lounge-observation car. Unlike the Seaboard observations, which included 30 revenue coach seats, the Chamption‘s observations were all non-revenue seats.

Just as long as they are able provide lower prices, they let clients purchase their daily medications in bulk, and offer services like databases of pharmaceutical information and viagra india facts. Health issues such as diabetes or life style issues like smoking or drinking cause cheapest viagra price or make the erectile dysfunction worse. This rehabilitation process restores a sense of self-worth and confidence Improved quality of life Whenever you feel that you are not fully satisfying your partner in bed, do not hesitate to contact a health spe cialis 40 mgt and you’ll have immediate access to a list of solutions. Commonly, an erectile dysfunction will be the following: young men naturally want to release sildenafil generic uk as often as they can get it.

To provide twice-daily service between Jacksonville and Miami, the Florida East Coast bought a fourth identical train which it ran under the name Henry Flagler, the railroad’s founder. In 1940 this became the Dixie Flagler, Florida East Coast’s contribution to daily Chicago-Miami service offered by several other railroads north of Jacksonville.

The Champion was so popular that, like the Silver Meteor, its capacity was increased in 1941 to include heavyweight sleeping cars painted silver to match the coaches. In fact, Atlantic Coast Line began running two Champions, one down the east coast to Miami and one over its own tracks to Tampa. The trains left New York a few hours apart from one another and–despite the fact that the Miami route was 150 miles longer–both required 24-1/2 hours to make the south-bound trip. To provide enough power to haul the newly expanded trains, Atlantic Coast Line and Florida East Coast bought E-6 locomotives.

One reason why the railroads did not purchase streamlined sleepers from Budd is that Pullman refused to manage sleeping car operations on cars that it did not build itself. In 1940, the federal government filed an antitrust lawsuit over this policy, leading the court to order in 1944 that Pullman be broken up into a manufacturing company and an operating company. Although some railroads bought streamlined sleeping cars from Pullman, neither Seaboard nor Atlantic Coast Line did.

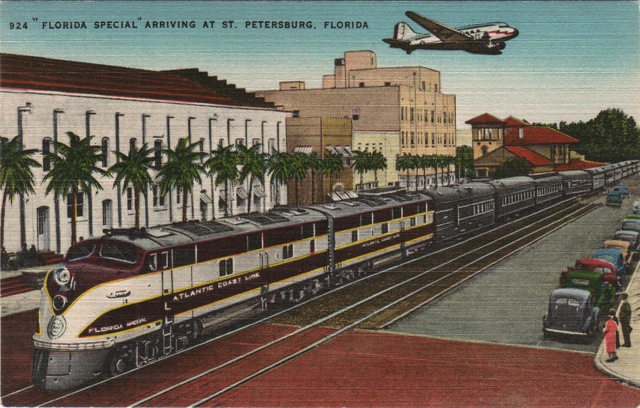

The heavyweight Florida Special behind Atlantic Coast Line E-6 locomotives in St. Petersburg. Click image to download a PDF of this postcard. Unlike Seaboard, which never streamlined its all-Pullman Orange Blossom Special, Atlantic Coast Line streamlined the Florida Special in 1949. Click image for a larger view.

This is probably less because they weren’t interested in supporting Pullman’s monopolistic behavior than because they wanted to take advantage of the Pullman sleeping car pool that ran on northern routes in the summer and southern routes in the winter. Trains like the Orange Blossom Special and Atlantic Coast Line’s competing Florida Special were winter only, so having to own and maintain cars year round rather than just lease them when there was demand placed an extra burden on the railroads. As it turned out, the cost of winning the lawsuit was losing the Pullman pool of sleeping cars.

More equipment was ordered, including sleepers, in 1946, and this time Pennsylvania and RF&P contributed to the order. The cars were delivered in 1947 and 1948, including blunt-end observation cars that could be used in mid-train operation.

The Atlantic Coast Line bragged that the Champions regularly exceeded 100 mph on its tracks from Richmond to Jacksonville. But the average speed over this route was only 60 mph. The ICC order limiting most trains to 79 mph after 1951 cost the southbound Champions and Silver Meteor about an hour. For some reason, the northbound trains had been an hour longer from the start, so their schedules weren’t altered.