The introduction of the second Empress of Britain was so momentous in Canadian Pacific ocean liner history that I’m using 1931, rather than 1930, to divide the ’20s from the ’30s in these posts documenting the empress fleet. The Britain, whose maiden voyage began on May 27, 1931, was the largest and fastest ocean liner ever to regularly serve Canada and, when she went on nine world cruises, she was the largest ocean liner to visit most of the ports she visited, including Los Angeles.

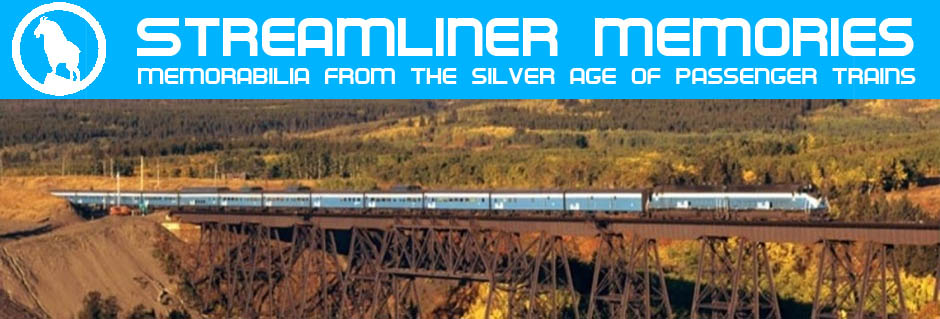

Click image to download a 34.8-MB PDF of this 28-page booklet. I redid the Chung collection’s PDF of this booklet to restore the colors and make pages correctly oppose one another. Click here to download a 63.5-MB PDF of the Chung collection’s version from the University of British Columbia library.

Click image to download a 34.8-MB PDF of this 28-page booklet. I redid the Chung collection’s PDF of this booklet to restore the colors and make pages correctly oppose one another. Click here to download a 63.5-MB PDF of the Chung collection’s version from the University of British Columbia library.

CP issued the above booklet early in 1931 to publicize the ship before photos were available. The cover painting — which wraps around the back; click here to download a 2.6-MB PDF of the full front- and back-covers — as well as thirteen interior paintings are by a then-unknown English artist, Frederick Griffin (1906-1976), who was only 24 years old at the time. He later did many travel posters for British railroads and airlines.

For the centerfold painting of the ship, however, Canadian Pacific turned to a more established artist, Kenneth Shoesmith (1890-1939). His maritime art was popular enough that someone later wrote a book about him and his paintings. Shoesmith did at least one more painting of the Britain that was used, with some variation, in this booklet and this poster. I suspect he was paid about as much for his two paintings of the Empress of Britain as Griffin was paid for fourteen.

Yet it is Griffin’s paintings that really show off the ship, at least as it would be enjoyed by first-class passengers. Canadian Pacific commissioned a lifeboat-load of artists and designers to decorate the lounges, dining room, ballroom, and other parts of the ship, and Griffin was able to capture many of their murals and decorations in his paintings.

- Sir Charles Allom (1865-1947), who had been knighted for his interior decoration work on Buckingham Palace, decorated the Mayfair Salon, one of the largest lounges on the ship.

- Sir John Lavery (1856-1941), who had been knighted for his work as an official artist during the Great War, decorated the Empress ballroom.

- Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956), who would be knighted in 1941 for his Great War murals and posters, decorated Salle Jacques Cartier dining room, which was named for the sixteenth-century French explorer who gave Canada its name.

- Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), a magazine illustrator and book designer, decorated the Cathay smoking room.

- Heath Robinson (1872-1944), a cartoonist and artist who was known for his Rube Goldberg machines (in England they are called Heath Robinson contraption) before Rube Goldberg, decorated both the Knickerbocker Bar and the children’s playroom.

- Percy Angelo Staynes (1875-1953), a painter and poster designer, working with A.H. Jones, about whom I can find no information, designed the Mall, a promenade connecting the Mayfair and Cathay lounges.

“The World’s Wonder Ship” was CP’s marketing slogan for the empress. This 1937 booklet has color photos showing many of the rooms illustrated in Griffin’s paintings on the first booklet above. Click image to view and download a 19.4-MB PDF of this booklet from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

“The World’s Wonder Ship” was CP’s marketing slogan for the empress. This 1937 booklet has color photos showing many of the rooms illustrated in Griffin’s paintings on the first booklet above. Click image to view and download a 19.4-MB PDF of this booklet from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

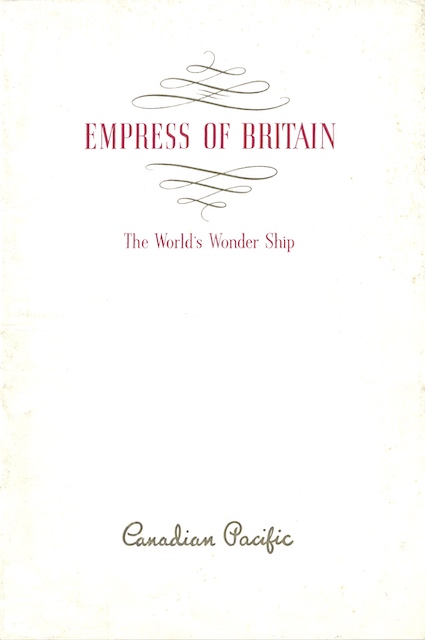

Canadian Pacific’s main message, however, was space: the Empress of Britain offered more space per person, to first-class passengers at least, than any previous ship. Instead of staterooms, the company insisted, the ship had apartments. In truth, these apartments were not significantly bigger than their counterparts on, say, the Empress of Australia except that far more of them had private baths: Where only 32 first-class staterooms on the Australia had private baths (11 percent of total rooms), a full 166 had them on the Britain. This was 42 percent of all rooms and 70 percent of first-class rooms.

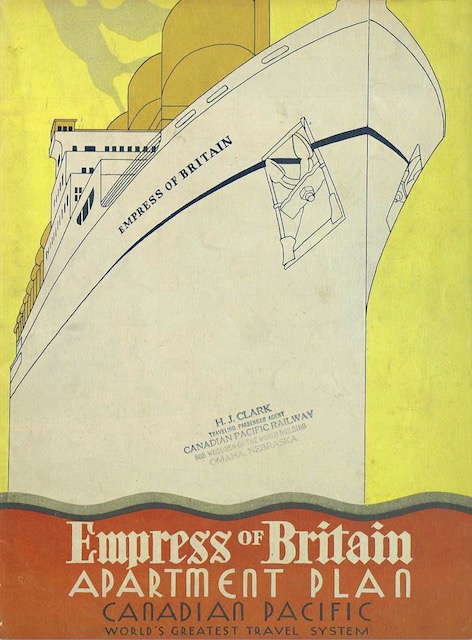

Of the various brochures issued by CP, this one has the best deck plans of the ship, showing all classes of accommodations. Click image to view and download a 3.6-MB PDF of this brochure from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

Of the various brochures issued by CP, this one has the best deck plans of the ship, showing all classes of accommodations. Click image to view and download a 3.6-MB PDF of this brochure from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

More space was found in the first-class lounges and recreation areas, which included a full-sized tennis court, squash courts, and an “Olympian” swimming pool (which, despite the name, was not Olympic sized). In total, these had much more space than on previous ships.

Second class (or, as CP called it, tourist class) and third class were not neglected. As shown in the brochure below, both classes had their own lounges, dining rooms, gymnasiums, children’s playrooms, barber shops, and hairdressers. These were smaller and with lower ceilings than their first-class counterparts, but at least people in these classes didn’t have to feel confined to their rooms. When they were in their rooms, all rooms had sinks with hot and cold running water and the third-class rooms, which might be shared with others, tended to have just two or four bunks, not ten to twelve as on earlier ships.

Click image to view and download a 16.8-MB PDF of this booklet from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

Click image to view and download a 16.8-MB PDF of this booklet from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

Although the Britain was rated to go 24 knots, its fastest time across the Atlantic averaged better than 25. When on world cruises, where time wasn’t as critical, two of its four propellers were turned off to save fuel.

The ship, which was built in Scotland, cost £2.1 million to construct, about $10.7 million in 1931 dollars and about US$170 million in today’s dollars. “Maybe we were a bit extravagant,” said Canadian Pacific in the above apartment brochure. In fact, the ship looked like a good investment when the company ordered it in 1928, but it had no idea that the world was about to enter the greatest depression in history. As it turned out, in the 192 trans-Atlantic crossings made by the Empress of Britain between 1931 and 1939, it carried an average of 493 passengers per voyage, just 41 percent of the ship’s capacity of 1,195 and well within the capacity of the smaller ships it replaced.

The empress made fewer than normal trans-Atlantic crossings in 1939 partly because King George VI and Queen Elizabeth chartered the ship to take them from Halifax, after a North American tour, to Southampton. Their party consisted of just 40 people. While this was great for Canadian Pacific publicity, it force the cancellation of three trans-Atlantic crossings the ship normally would have made.

More trips were cancelled when war was declared in September. The Empress of Britain‘s last sailing for Canadian Pacific left Southampton on September 2. For once, she was filled beyond capacity with people fleeing Europe.

After that voyage, she was impressed into service as a troop transport. During the wars, the ships Britain and other ships were chartered to the U.K. government for the duration. They remained in Canadian Pacific ownership and were crewed by Canadian Pacific employees who were putting their lives at risk from enemy action.

On October 26, 1940, a German bomber sighted the Empress of Britain and its attack caused some damage. Two days later, alerted to the ship’s distress, a U-boat that ordinarily wouldn’t have been able to catch the fast ocean liner sank it with torpedoes. Fortunately, all but 45 of the 623 people on board were rescued, but it was the largest ship sunk by a U-boat during World War II. Two days after that, the U-boat that sank her was itself sunk and many of its rescued crew were sent to Canada as prisoners of war on another Canadian Pacific ship, the Duchess of York.

In November, the Church of St. Andrew and St. Paul in Montreal held a memorial service for the ship and lost crew. A month later, Canadian Pacific published a short booklet memorializing the empress and distributed it to the ship’s former passengers.

Some of the information in this post is from Gordon Turner, Empress of Britain: Canadian Pacific’s Greatest Ship (Toronto: Stoddard, 1992), 216 pages.