The 20-hour Exposition Flyer gave the Central a public relations boost over the Pennsy, but George Daniels’ real publicity coup in 1893 was to persuade the New York Central to build a high-performance version of its standard passenger locomotive, in the same way that auto makers today make a few high-performance cars to help publicize their regular automobiles. At the time, the Central and its subsidiaries were buying 4-4-0 locomotives from Schenectady (a predecessor of Alco) that typically had 18″x24″ pistons, 180 pounds of boiler pressure, and 69″ to 78″ driving wheels.

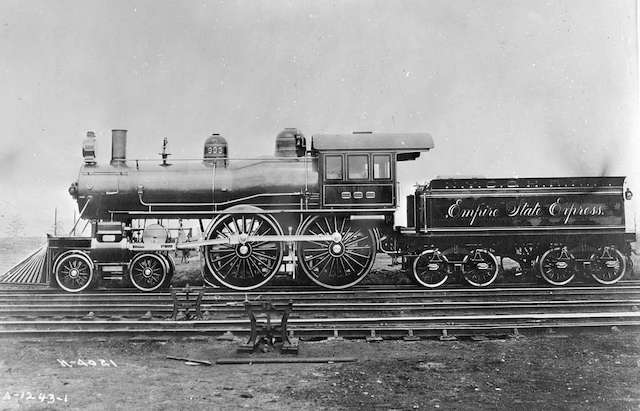

This photo makes locomotive 999 look a little stubby, but that’s because its boiler and driving wheels were so much larger than normal. Its wheel base, including tender, was actually longer than a typical New York Central 4-4-0 of the time.

To increase power, the high-performance locomotive, which Daniels dubbed the 999, would have 19″x24″ pistons and 190 pounds of boiler pressure, each change making the locomotive about 5.6 percent (for a combined 11.4 percent) more powerful than the railroads’ standard 4-4-0. This extra power was needed because, to reach high speeds, the 999 would sport driving wheels that were 86-1/2″ in diameter. While a few British locomotives had 90″ drivers, the 999’s drivers were quite likely the tallest ever used in America. The large drivers reduced its tractive effort to about 15,400 pounds compared with around 17,000 for a more typical NYC 4-4-0 of the time.

To ensure the locomotive would be able to produce enough steam to sustain high speeds, 999 had a much larger boiler and firebox than normal. Where the Central’s typical 4-4-0 had 1,570 square feet of evaporative heating area in its firebox and boiler tubes, the 999 had 1,930 square feet or 23 percent more. To enhance its appearance, 999’s boiler was jacketed in Russia iron, a glossy sheet metal that was often used on prominent steam locomotives. Judging from the few color illustrations of the locomotive, this gave it a greenish hue.

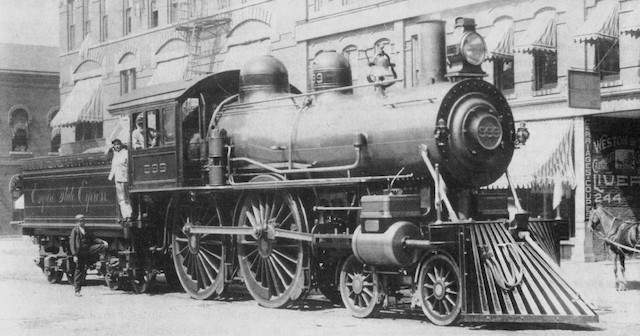

The 999 in Syracuse, with engineer Charlie Hogan at the throttle, about the time of the locomotive’s record-breaking attempt. Click image for a larger view.

The weight of the bigger boiler helped to compensate for another problem with the larger drivers: they tended to slip when starting. The big boiler put 84,000 pounds on the drivers compared with 66,400 for a more typical 4-4-0, but the locomotive was still slippery and its low tractive effort limited the number of cars it could pull. This didn’t matter for the Empire State Express or Exposition Flyer, both of which tended to have just four or five cars.

Designed by the railroad’s superintendent of motive power, William Buchanan, the 999 had been built for a single purpose: to power the first train in history to go faster than 100 miles per hour. May 10, 1893 was the 24th anniversary of the joining of the First Transcontinental Railroad, and many Americans alive in 1893 keenly remembered that event. Daniels was aware of this when he set that date for the locomotive’s record-setting attempt. Pulling a standard train of four cars weighing 181 tons, the 999 entered a six-mile straightaway between Rochester and Buffalo and accelerated as fast as it could go before having to slow down for a curve at the end of the straightaway.

The 999 leads the Empire State Express on the day of its record-breaking effort in this picture by New York Central photographer Arthur P. Yates. While some captions imply that this photo was taken during that attempt, in fact it was taken when the train was at rest. For one thing, the smoke was “photoshopped” in later, which is revealed by the fact that the smoke cloud is identical to that found above the locomotive in a completely different photograph that was also taken by Yates. Click image for a much larger view.

With senior engineer Charles Hogan at the throttle, New York Central vice president Walter Webb used his watch to measure the time between mileposts. The day before, May 9, they had tested the locomotive and claimed that it covered the distance between two mileposts in 35 seconds, or 103 miles per hour. On May 10, with members of the media on board, Hogan went faster still, going one mile in as little as 32 seconds, or more than 112 miles per hour. Webb actually claimed a mile in 31.5 seconds, but rounded up to 32 to calculate miles per hour.

This generated enormous publicity for the railroad. “Probably most adults and every male youngster in the U.S. heard about the engine’s world-record run, its locomotive engineer Charlie Hogan, and designer Buchanan,” says William Withuhn in American Steam Locomotives. Nearly a century before they had their own TGV, the French called it “Trains de grande vitesse,” or high-speed train. The 999 received effusive praise from a wide variety of sources.

This photo supposedly shows the 999 on display at the Columbian Exposition. But why is there snow on the ground when the expo went from May 1 to October 30? Why does the building in the background look like some kind of industrial or freight office rather than a fair exhibit? Why is the locomotive displaying white flags, which designate an extra (i.e., unscheduled) train? While snow in Chicago isn’t impossible in May or October, it is more likely this photo was taken as the locomotive was preparing to leave after the fair ended, which would have been early November. Click image for a larger view.

There were also skeptics. “These claims of terrific speed are not official and we do not believe that the engine ran 100 miles an hour,” opined the editors of Locomotive Engineering magazine in June, while admitting that it “has probably made the highest speed of any locomotive in the world.” Despite its doubts, the magazine happily accepted advertisements from companies whose products contributed to the 999 and published numerous reports of people praising the beauty and technology of the new locomotive.

As Withuhn points out, there are two problems with the 112 mph claim. First, the measuring devices of the day were crude: locomotives didn’t have speedometers, the railroad provided no on-the-ground observers, and Webb’s watch probably was not a stopwatch. At 100 miles per hour, mileposts would have been a blur and watching for the mileposts and the second hand on a watch at the same time could easily result in errors of two seconds or more.

Second, it is unlikely that the 999 was physically capable of going that fast. At 112.5 miles per hour, an 86-1/2″ wheels would have been turning almost 440 revolutions per minute and each piston would have had to exhaust its steam in less than 0.07 seconds. Nor is it clear that the 999’s firebox and boiler were large enough to sustain 190 pounds of pressure for several minutes while using that much steam.

A rough rule of thumb was that a steam locomotive could go the diameter of its driving wheels in inches plus ten in miles per hour. That meant 96-1/2 mph for the 999.

In 1943, Norfolk & Western built 4-8-4 J-class locomotives that once reached 110 miles per hour despite having just 70″ driving wheels. That meant that the drivers would have to turn 528 revolutions per minute and pistons would have just 0.057 seconds to exhaust their steam. But the Js benefitted from 50 years of improvements on piston valves, including newer Baker valve gear instead of the much older Stephenson valves used on the 999. They also had 275 psi boilers, superheaters, and nearly 7,450 square feet of heating surface, nearly four times as much as the 999.

In any case, based on locomotive power relationships published by Alco in 1913, Withuhn concludes that the 999 probably could go faster than 100 mph, but almost certainly could not have reached 112 mph. But none of this mattered to the New York Central, which undoubtedly saw a surge in riders on both the Empire State Express and Exposition Flyer as a result of the publicity generated by the locomotive.

The 999 on display at a rail fair in Louisville in 1960. The locomotive had received a new boiler, new tender, air pumps and an air reservoir for the brakes, a new bell and whistle, a small steam-powered generator to power the headlight, and smaller driving wheels, so it really wasn’t the same engine that may have gone over 100 mph in 1893. Click image to download an 874-KB PDF of this postcard with photo by Mac Owen. Thanks to Audio-Visual Designs for permission to use this card.

Upon completion of its famous run, the 999 went to the Wagner shops in East Buffalo to pick up new cars that would be put on display with it at the Columbian Exposition. In accordance with the theme of the exposition (which commemorated Columbus’ first visit to the New World), the cars were named Columbus (buffet-smoking car); Ferdinand (dining car); San Salvador (stateroom sleeping car); Isabella (double stateroom sleeper); and Pinzon (parlor car). Wagner promised that these would be the “five finest railroad cars the world has ever seen.”

According to an article in the May 20, 1893 Buffalo Enquirer, the five cars were painted royal blue with gold trim and lettering. Even the trucks were painted with a gold lacquer. The steps, railings, and other key metal parts were highly polished brass. Interiors used a variety of inlaid and hand-carved woods and were decorated with paintings illustrating the “progress of art.” Everything was made with “the finest and costliest materials obtainable” in order to produce “perfection.” The locomotive and train became a hit of the fair.

The 999 today in the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry. Photo by Sean Lamb.

After the exposition, the Central replaced the 999’s drivers with ones that were 78″ tall. These still proved slippery so in 1899 they were again reduced to just 70″. The locomotive earned its pay pulling the Empire State Express for several years. After having its boiler replaced in the 1920s and the boiler jacketing painted black, it operated on progressively more local trains, ending up as a switch engine before being retired at the ripe old age of 59 in 1952. Cognizant of its history, the railroad preserved it and, in 1968, donated it to the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry, where it currently sits on its smaller drivers.