The end of the World’s Columbian Exposition also saw the end of the Exposition Flyer‘s 20-hour schedule. Initially, New York-Chicago passengers had to be content with journeys of at least 26 hours. In September 1894, the Central speeded up its New York and Chicago Limited to a 24-hour schedule, still four hours more than the Expo.

The first run of the 20th Century Limited in 1902. Photo by Arthur P. Yates.

The first run of the 20th Century Limited in 1902. Photo by Arthur P. Yates.

George Daniels returned to the 20-hour timetable when he introduced the 20th Century Limited in 1902. This train proved to be his crowning achievement, as he became known as the “Father of the Century.” Having already conceived of the Red Cap porter, Daniels introduced red carpet service by rolling out red carpets for passengers to walk on before boarding the Century.

The epitome of a limited train includes three factors: speed, exclusivity, and amenities. Speed was attained by reducing the number of stops. Exclusivity was attained by excluding coaches and tourist sleepers and adding extra fares. Amenities included barbers, hairdressers, shower baths, libraries, and fancy observation cars. Not all limited trains had all three factors, but the 20th Century Limited had them in spades.

The 20th Century Limited not only made just eight stops between New York and Chicago, these were exclusively to service the train and engine. “This train carries passengers only for Chicago and points west of Chicago, and passengers are required to have an excess fare in addition to the first-class passage ticket,” advises the 1902 Official Guide about the westbound train.

Locomotives

To pull the original Century, the railroad relied heavily on 4-6-0s such as the one in the above photo, which produced about 24,000 pounds of tractive effort. It also used 4-4-2s such as the one in the postcard below. These were a little newer but produced only about 23,000 pounds of tractive effort.

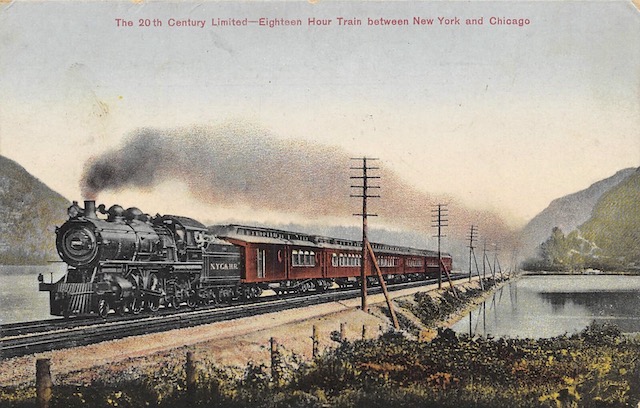

This postcard advertises the 20th Century Limited taking 18 hours from New York to Chicago, dating it to 1905 or later. However, the colorized picture is based on a 1902 photo by A.P. Yates. Click image to download a 1.5-MB PDF of this postcard.

This postcard advertises the 20th Century Limited taking 18 hours from New York to Chicago, dating it to 1905 or later. However, the colorized picture is based on a 1902 photo by A.P. Yates. Click image to download a 1.5-MB PDF of this postcard.

In 1907, the New York Central started ordering large numbers of 4-6-2 Pacific-type locomotives. Most of these did not have superheaters installed when delivered from the builder, but the Central later installed them. Many of the early models had about the same driver diameters (69″) and boiler pressures (180 psi) as many of Central’s 4-4-0s, but much larger pistons, such as 26″x26″. This resulted in tractive efforts of close to 39,000 pounds, a big jump from the previous locomotives. Those intended for fast trains had 79″ drivers, which — despite boiler pressures of 200 psi — reduced tractive effort to around 29,000 pounds.

In the 1920s, long distance rail travel boomed and many people wanted to ride fast trains such as the 20th Century Limited. Pacific-type locomotives weren’t sufficient for trains longer than about 12 cars, and running multiple sections added to operating costs. Many other railroads had purchased 4-8-2 Mountain-type locomotives for heavy-duty passenger service. Although the New York Central ended up owning more 4-8-2s (which it called Mohawks because it didn’t want anyone to think that its “water-level route” had to go over mountains) than any other railroad, it used them almost exclusively for fast freight trains.

This is one of 205 Hudsons built by Alco for the New York Central in 1927. It had 79″ drivers and was almost three times as powerful as the 999. Its total weight including the tender was well over three times as much as the 999. Click image for a larger view.

Instead of a 4-8-2, the railroad’s chief mechanical engineer, Paul Kiefer, proposed to add a four-wheel trailing truck to the 4-6-2, thus allowing for a bigger firebox that could support a more powerful locomotive. The first 4-6-4 Hudsons, as the Central called them, were produced in 1926 and they became popular on many other railroads that had gentle grades, including the Burlington, Illinois Central, and New Haven. Apparently, many railroads believed eight drivers were needed for mountain railroading and heavy freights, and railroads such as the Santa Fe and Baltimore & Ohio had Hudsons for their flatter regions and Mountains or Northerns for their mountain districts.

The Central’s Hudsons came with 25″x28″ pistons and either 75″ or 79″ drivers. The smaller-driveled locos produced 47,600 pounds of tractive effort, while those with 79″ were able to go faster at the sacrifice of producing only 42,366 pounds, which was still enough to speed 16 to 18 passenger cars between the East Coast and Midwest. Naturally, the larger-drivered locomotives were dedicated to fast trains such as the 20th Century Limited.

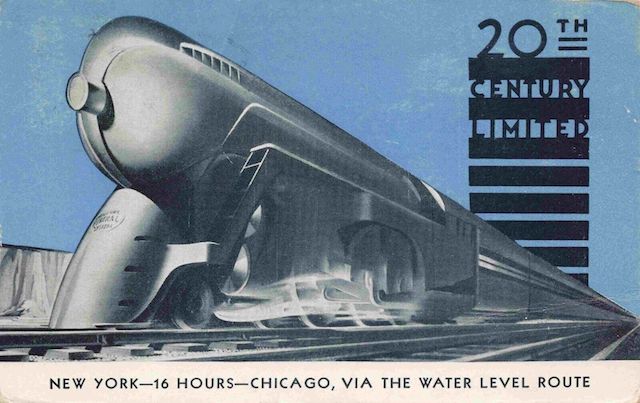

In 1934, the railroad responded to the streamlining movement by putting an upside-down bathtub-style shroud on one of its Hudsons, advertising it as the first streamlined steam locomotive in the world. Perhaps stung by the bathtub allusions, the railroad then hired industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss to design a bullet-nosed streamlined locomotive and it ordered ten Hudsons built to his specifications, which were delivered in 1939. Drefuss also designed the interiors of the feature cars of the streamlined 20th Century Limited that were introduced that year. These locomotives became symbolic of speed and beauty in the pre-jet age, such much so that in 1939 the Hudson that had the bathtub shroud was refitted with one to Dreyfuss’ design.

This highly stylized image of a highly stylized locomotive was used on a postcard stamped “First Trip of the New Streamlined 20th Century Limited. Click image to download a 1.6-MB PDF of the postcard.

In 1945, the New York Central bought 27 4-8-4 locomotives (which it called Niagaras). It tested these against Diesels and found that they cost a lot less to buy and only a little more to operate. Overall the steam locomotive had a slightly higher cost per mile but was also much more powerful, so the annual cost per horsepower was only about half as much as the Diesel. Nevertheless, the Diesels swept the steamers away and by 1956 all of the Niagaras were retired and scrapped.

Speed

The Century‘s 20 hours were reduced to 18 in 1905, resulting in an average speed of 54-1/3 miles per hour. Because the Central’s route was about 70 miles longer than the Pennsylvania’s, the Century‘s average speed was several miles per hour faster than PRR’s entry into the 18-hour sweepstakes, leading Daniels to advertise it as the “fastest long-distance train in the world.” Thanks to Daniels’ efforts, the Central was also able to advertise it as the “most famous train in the world.”

Apparently, 18 hours was just a little too ambitious in the 1900s. Lucius Beebe’s book, 20th Century, has an appendix showing that, starting in 1908, times increased to 19-1/2 hours. For the next four years, they fluctuated between 18 and 19-1/2 hours and then were increased back to 20 in 1912. There they remained until 1932 when they dropped again to 18. Over the next six years, times slowly declined to 16 hours in 1938. The shortest times began in 1947, when they dropped to 15-1/2 hours eastbound, for an average speed of 62 miles per hour. This was short-lived, however, returning to 16 hours in 1951, which was still faster than 60 miles an hour.

Extra Fare

Over the years, the extra fare charged for riding the Century (and Pennsylvania’s comparable train) ranged from $3 to $10. When adjusted for inflation, it ranged from $79 to $322. When adjusted for the number of hours a typical production worker would have to work to pay that fare, it ranged from $116 to $1,850. (In other words, to earn the $8 extra fare, a 1902 production worker would have to work the same amount of hours that would earn them $1,850 today.)

| Year | Extra Fare | Today's Dollars | Relative Wages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1902 | $8 | $284 | $1,850 |

| 1908 | 10 | 322 | 1,960 |

| 1912 | 8 | 250 | 1,470 |

| 1920 | 9.6 | 142 | 611 |

| 1932 | 10 | 157 | 675 |

| 1935 | 7.5 | 162 | 475 |

| 1942 | 3 | 55 | 120 |

| 1947 | 5 | 66 | 132 |

| 1957 | 7.5 | 79 | 116 |

Of course, the Century wasn’t the only train on which the Central charged an extra fare. The New York Central’s 1930 timetable (downloadable from the Canada Southern web site) lists 25 trains in the New York-Chicago corridor (five of which also had sections to St. Louis) for which an extra fare was charged to at least some passengers (some short-distance passengers did not have to pay an extra fare on some trains).

The New York-Chicago fares were as low as $3.60 for the westbound Niagara, which took 25-2/3 hours, while the 20-hour trains all charged the same $9.60 extra fare as the Century. Only five eastbound and just two westbound trains charged no extra fare, and these tended to take close to 30 hours or more to get between New York and Chicago.