On December 12, 1911, just one week after the Southern Pacific reinaugurated the Sunset Limited, Santa Fe threw down the gauntlet in the Chicago-Los Angeles market by introducing a train that may have been the poshest, most exclusive passenger train ever operated by any major American railroad. Named the de-Luxe (sometimes with a hyphen, sometimes with a space, but never “deluxe”), the once-a-week, winter-only train had as many non-revenue seats as the California Limited, but according to this brochure at the Kansas Historical Society, the train was limited to just 60 passengers. This led Lucius Beebe to describe the train as “unbelievably opulent.”

This photograph of the de-Luxe was taken by a Detroit Publishing photographer, quite possibly William Henry Jackson. Aside from the more modern locomotive, the train outwardly has the same consist as the original California Limited: a baggage-buffet-smoker-library car, a diner, and four sleeping cars, the last of which was also an observation car. The locomotive is a 4-6-2 Pacific built in 1909. Despite not being fitted with superheaters until 1920, well after this photo was taken, the loco produced a respectable 37,810 pounds of tractive effort. Click image for a much larger (2.5-MB) view.

Part of the train’s opulence was in the configuration of its sleeping cars. Where 60 out of the 93 beds of the California Limited were in open sections, three out of four of the beds in the 1912 de-Luxe were in rooms. According to this 1912 brochure, the first two sleeping cars consisted of seven drawing rooms for 21 potential beds each, followed by a third all-room car with seven compartments and two drawing rooms for 20 potential beds. Open sections were found only in the observation car, which like that of the California Limited had 10 sections or 20 beds.

This is a total of 82 beds, or 22 more than the capacity limit in 1911. Yet ads from 1913 confirm that the limit of 60 passengers remained in force. Of course, not all of the rooms would necessarily be full and some people might pay for an entire section for one rather than just a lower berth.

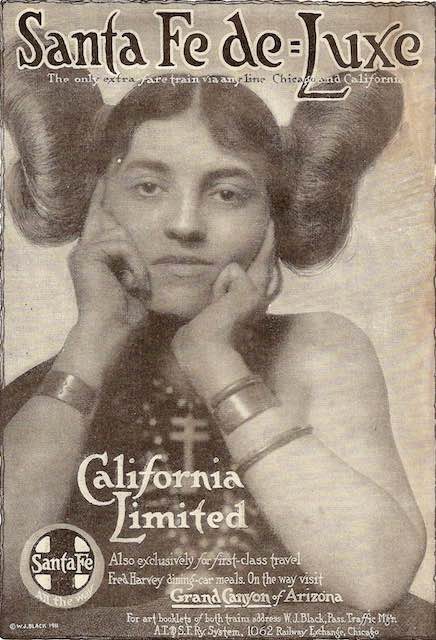

Santa Fe de Luxe ads early featured photos of Indian and white women. Note that the photographer of this Hopi Indian woman was Santa Fe’s passenger traffic manager. The woman, who also appears on at least one Fred Harvey postcard, is wearing a squash blossom whorls hairstyle, signifying her eligibility for marriage. Click image for a larger view.

Santa Fe de Luxe ads early featured photos of Indian and white women. Note that the photographer of this Hopi Indian woman was Santa Fe’s passenger traffic manager. The woman, who also appears on at least one Fred Harvey postcard, is wearing a squash blossom whorls hairstyle, signifying her eligibility for marriage. Click image for a larger view.

(Unfortunately, the Kansas Historical Society requires payment for reproducing its scans of documents on other web sites. Since Streamliner Memories earns no revenue, I’ll just link to the KHS brochures.)

Initially, Santa Fe resisted the use of all-steel cars, saying that they were difficult to insulate. As one railroad executive put it, steel cars were “ice cream freezers in the winter and bake ovens in the summer.” Instead, the de Luxe used new wooden cars with steel underframes. By 1913, Santa Fe bowed to competitive pressure and replaced the composite cars with all-steel cars.

For the 1911 season, the Santa Fe coined the phrase, “Extra Fast, Extra Fine, Extra Fare.” We’ve previously seen that phrase on a 1948 brochure advertising the streamlined Golden State. Compared with the Super Chief and City of Los Angeles, the Golden State in 1948 was neither extra fine nor extra fast, so the extra fare was warranted only when compared with Southern Pacific-Rock Island’s secondary Chicago-Los Angeles train, the Apache.

The de-Luxe, however, took 63 hours between Chicago and Los Angeles, which was several hours less than any other train between Chicago and Los Angeles. It also had finer accommodations, so the extra fare was deserved.

Notice in the ads that the extra fare was used as a selling point: people riding an extra-fare train knew that other passengers on the train were in their income class and thus they wouldn’t have to deal with people from the “lower classes.” As a 1918 booklet says, riding the de-Luxe would allow passengers “To meet the class of persons you associate with at home and at your club.”

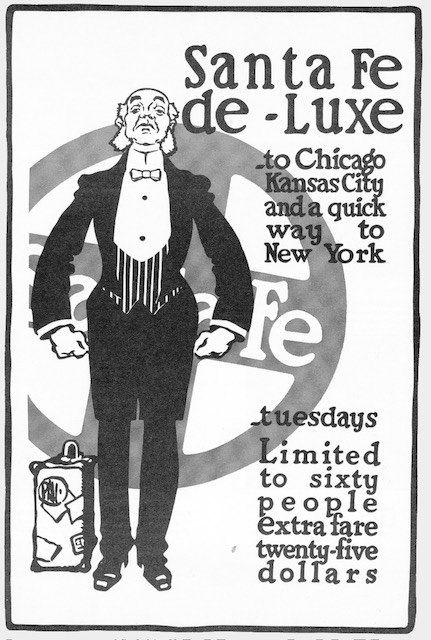

This 1913 ad emphasizes the exclusive nature of the train. Click image for a larger view. The ad was designed by Louis Treviso (1888-1928), who also designed many Santa Fe posters.

This 1913 ad emphasizes the exclusive nature of the train. Click image for a larger view. The ad was designed by Louis Treviso (1888-1928), who also designed many Santa Fe posters.

I suspect the term “extra-fare” grew out of Interstate Commerce Commission regulation of railroad rates. Prior to such regulation, railroads could charge whatever the market would bear, so the rates on some trains (such as the Golden Gate Special) would simply be higher than for more routine trains.

With rate regulation, fares were published for any possible trip and the fare for a longer trip could not be less than the fare for a shorter trip. Railroads could charge higher rates only if they could justify that the service they were providing was faster or better.

Santa Fe charged no extra fare for the California Limited. The first extra-fare train was Pennsylvania’s New York & Chicago Limited, which started operating in 1881. When the 20th Century Limited and Pennsylvania Special (predecessor to the Broadway Limited) began operating in June, 1902, they charged a $10 extra fare to go between New York and Chicago.

Ten dollars doesn’t sound like much, but adjusted for inflation it is more than $320 today. Moreover, skilled working-class workers earned far less than today; for them, $10 was the equivalent of working enough hours to earn $2,000 today.

Even the drumhead of the Santa Fe de-Luxe bragged that it was an extra-fare train. Click image for a larger view.

Even the drumhead of the Santa Fe de-Luxe bragged that it was an extra-fare train. Click image for a larger view.

The 20th Century and Pennsylvania Special were cheap compared with the de-Luxe, which charged a whopping $25 extra fare in 1911. Admittedly, this was for a trip that was roughly two-and-one-half times longer, but it’s more than $800 in today’s dollars and $4,800 in equivalent factory-worker hours. That would certainly be enough to keep the riff-raff off the train. As Santa Fe said in the 1911 brochure, “We know the service on this train is worth $25, which is the extra fare charged.”

The de-Luxe was distinguished from other West Coast trains in another way: between Chicago and the Los Angeles area, passengers could get off only in Kansas City or Williams (to see the Grand Canyon). In southern California, the train stopped to pick up or drop off passengers in San Bernardino and Pasadena as well as L.A. Although the train also made scheduled stops in Newton, KS; La Junta, CO; Albuquerque, NM; and Ash Fork, AZ, those were just to change crews and service or change the locomotives.

Although the train was advertised for the 1918-1919 season, it was cancelled due to the war and not revived after the war. Before the war, in addition to the de-Luxe, Santa Fe had three trains to Los Angeles: the California Limited, the California Fast Mail, and the Los Angeles Express. After the war, it had four: the California Limited, the Navajo, the Scout, and the Missionary, so it must have decided that a fifth winter train wasn’t necessary.

Nevertheless, the de-Luxe became the standard against which other limited trains would be judged for many years. The word “deluxe” began to appear much more frequently in railroad advertising. While I have found one 1906 railroad ad that uses the term, this was an exception, whereas after 1911 nearly every railroad that operated a limited train used the term in one ad or another.