For nearly 70 years — roughly 1902 through 1971 — the competition for passenger business between Chicago and Los Angeles was nearly as intense as that in the New York-Chicago corridor. When Santa Fe arrived in southern California in 1887, however, Los Angeles was only a small city of around 40,000 people, compared with San Francisco’s 275,000. Yet L.A. was one of the fastest-growing cities in the nation, surpassing San Francisco by 1920 and doubling its size by 1930.

This photo of the California Limited was taken by William Henry Jackson at Santa Fe’s Los Angeles passenger station in the late 1890s. Click image for a larger view.

Southern Pacific was already serving Los Angeles when Santa Fe arrived, but passengers from Chicago would have to spend an extra day or more taking SP trains via New Orleans or Ogden. SP’s New Orleans-Los Angeles route opened in 1883, but passengers first had to get to New Orleans and then had to change trains again in El Paso. The Overland Route via Omaha and Ogden also required passengers to change trains in Omaha.

Though Santa Fe’s route was more direct, it was initially no speed demon. Santa Fe didn’t begin offering through trains from Chicago to Los Angeles until 1891, and when it did the trains took about 95 hours, an average of less than 24 miles per hour. Despite slow service, competition pushed Kansas City-California fares down from $125 to $25 and, on March 6, 1887, to just $1. Many believe that this rate war greatly contributed to the Los Angeles’s rapid growth after that time.

Southern California’s fast-growing population and mild year-round climate prompted Santa Fe to introduce the California Limited in November, 1892, a winter-only, first-class train. Although it later became an all-Pullman train, initially it included tourist sleepers and chair cars for at least part of its journey. Although Los Angeles was the biggest city in southern California, the train also had a section to San Diego. Another section that went to San Francisco initially carried more passengers; some early ads for the train don’t even mention Los Angeles.

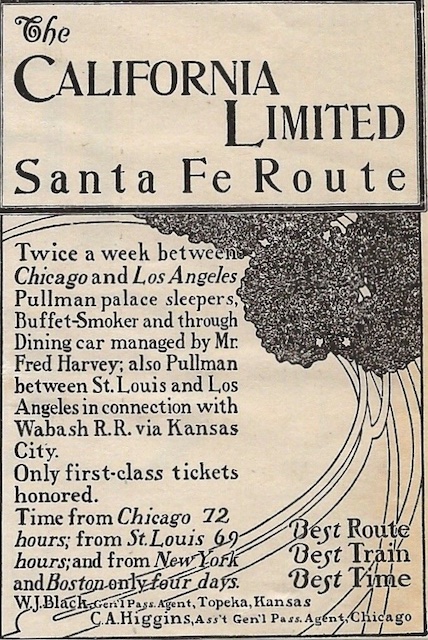

The Chicago-Los Angeles time for the train was down to 72 hours by 1897, when this ad was published. Click image for a larger view.

The Chicago-Los Angeles time for the train was down to 72 hours by 1897, when this ad was published. Click image for a larger view.

Initially, only the westbound train was called the California Limited. In recognition of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, the eastbound counterpart was the Columbian Limited until 1896 when it became the Chicago Limited. After 1897, it was called California Limited in both directions except in 1900, when the eastbound train was again briefly called Chicago Limited.

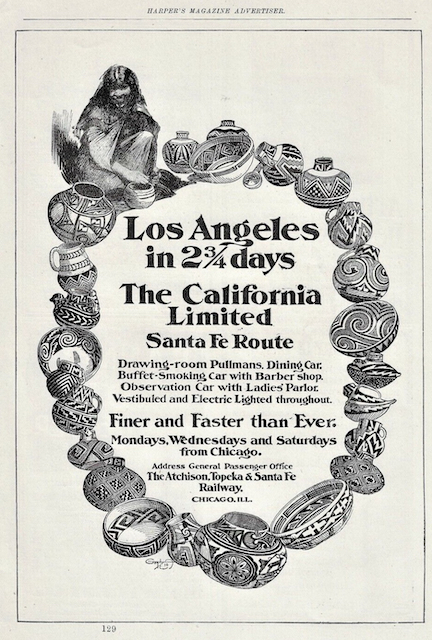

Whatever the names, these were true limited trains: by greatly reducing the number of stops, the time between Chicago and Los Angeles was cut by 11 hours for an average speed of 27 mph in 1892. Speeds improved until 1898, when the time dropped to as low as 66 hours or more than 34 mph. It hovered around there until 1929, when it was dropped to 63 hours or 36 mph.

By 1898, this ad claimed the time was down to 66 hours. This may have been true for the eastbound train, but westbound trains usually took a little longer. Click image for a larger view.

By 1898, this ad claimed the time was down to 66 hours. This may have been true for the eastbound train, but westbound trains usually took a little longer. Click image for a larger view.

The California Limited was also the first Santa Fe train with a dining car, and the railroad’s desire to include dining cars may have delayed the introduction of the train by a year. According to the April 4, 1892 issue of Railway Age, Santa Fe purchased its first dining cars in 1890, but Fred Harvey saw the cars as a violation of his contractual monopoly on serving meals to Santa Fe passengers. Harvey sued and the issue was settled when Santa Fe agreed to let Harvey manage the dining cars. Still, for many years thereafter, most Santa Fe trains continued to stop at Fred Harvey restaurants rather than carry a diner.

The California Limited began as a daily train, but in 1897 it was cut back to twice a week. This increased to three times a week in 1899, four times in 1900, and back to daily in 1901. Also in 1901, Santa Fe began operating the train year round. Though initially only twice a week in the summers, by 1907 (and perhaps a year or two before, as my timetables are incomplete) it was daily year round.

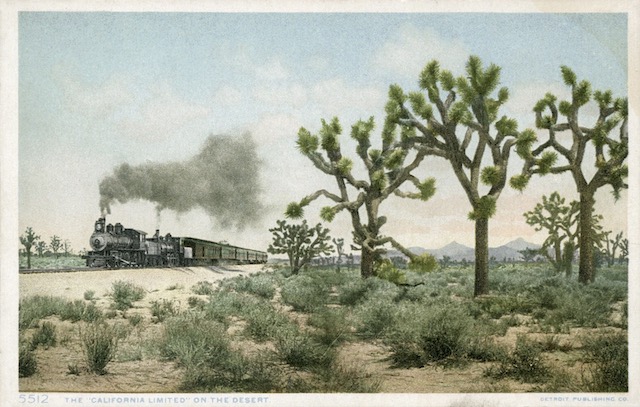

William Henry Jackson’s photo shows the typical motive power for the early California Limited. The 4-6-0 locomotive was built by Baldwin in 1887 and is numbered 53 for the Southern California Railway, a Santa Fe subsidiary. In 1902 it would be renumbered to Santa Fe 396.

Having six driving wheels instead of four allowed for a larger firebox to generate more steam, but the small size of the drivers — 58″ — limited top speeds to much less than, say, the Empire State Express, which in 1892 was typically pulled by locomotives with 69″ drivers. With a tractive effort of nearly 21,000 pounds, this locomotive was designed to pull trains over the mountains, not break speed records.

The photo of the California Limited on this Fred Harvey postcard was probably also taken by William Henry Jackson. Another postcard with this photo copyrights it 1901, meaning it was taken no later than that year but could have been taken before. It is likely that it was taken within a few days of the first photo above. Click image to download a 316-KB PDF of this postcard.

However, the above postcard shows that two locomotives were needed to pull the six-car train over the San Bernardino Mountains. Both locomotives on the postcard, like the one in the previous photo, are 4-6-0s.

The first car in the six-car train shown in the first photo was a buffet-smoker named San Bernardino. Judging from the rooftop vents, the car following it is a diner. This was followed by four cars of different configurations, with two appearing to be chair cars and two sleepers. Normally, the train would pick up the San Diego car in San Bernardino and a Denver car at La Junta. The train in the postcard is probably similar and may in fact be the very same train.