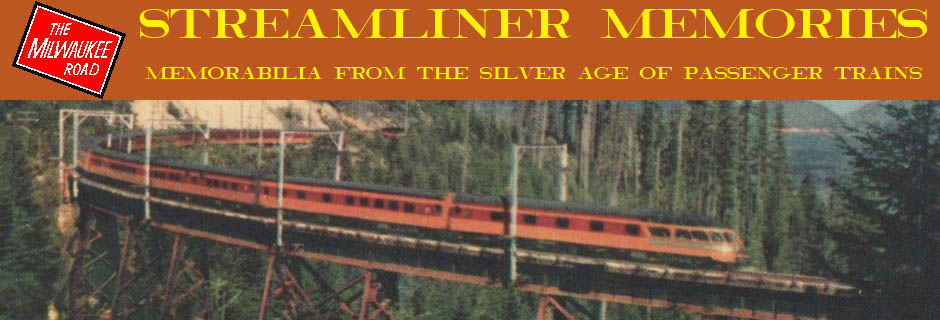

In November, 1949, less than three years after introducing the streamlined Empire Builder, Great Northern announced that it was spending $9 million on 66 new cars that would make up a brand-new Empire Builder to be placed in service in 1951. The 1947 equipment, meanwhile, “will be transferred to the run of the Oriental Limited between the same terminals.”

Click image to download this 14.2-MB PDF of 78 pages of documents.

Click image to download this 14.2-MB PDF of 78 pages of documents.

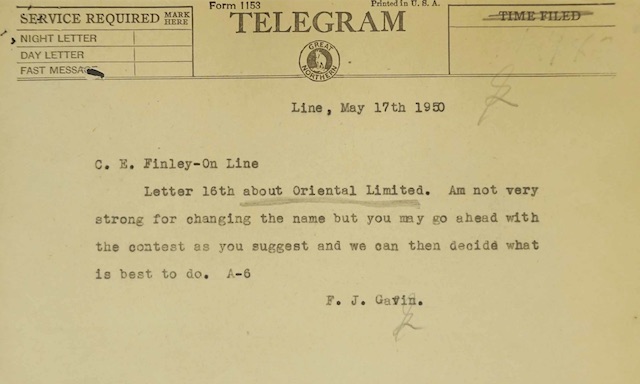

The following May, however, GN traffic vice-president C.E. Finley warned President Frank Gavin that the Oriental Limited, trains 3 & 4, was “known as a train containing old or conventional equipment.” The best way to change this impression, he suggested, was to change the name, adding that “our passenger men are 100% agreed.” To find a new name, Finley proposed a contest open to all off-line ticket agents.

On one of my visits to the Minnesota History Center, I photographed documents about this contest and reported on it in the September, 2018, issue of the Great Northern Railway Historical Society’s Great Northern Goat. These documents are pretty self-explanatory, but because most Streamliner Memories readers probably do not get the Great Northern Goat, I’m going to summarize them here.

As indicated in the telegram above, Gavin wasn’t convinced about the need to change the name. Having gone to work for the Great Northern in 1899, six years before the first run of the Oriental Limited, President Gavin was a generation older than most of his staff. To him, the name Oriental Limited represented a fabulous luxury train. Vice president Finley and operations vice president John Budd had both started working for GN after graduating from Yale in 1929, right about the time the Empire Builder replaced the Oriental Limited as GN’s premiere train. To them, Oriental Limited was an outdated secondary train.

While Gavin liked Oriental Limited, he also believed in delegating authority. As a result, in September, 1950, the railway announced the contest for the new name. In fact, it had two contests: one for off-line ticket agents and one for Great Northern employees. The railway designated a committee of judges including Al Kalmbach, the publisher of Trains magazine, and Henry Comstock, the editor of Railroad magazine. However, it reserved the right to select a name other than the one or ones picked by the judges.

Contestants were asked to submit names by November 30 and were invited to include a 25-word statement favoring the name. In case two or more people proposed a name selected by the judges, the 25-word statement would be the tie breaker. The contest winners would each get $500 (about $5,000 today), and more than one person in each contest could win the prize if there was still a tie after reading the 25-word statements.

Although the contest rules offered no hints about what the railway wanted, correspondence within the company and to some outside indicated that the name should not duplicate the name of a train already in use and that it should be a name “associated with the West.” In all, more than 7,500 entries were submitted, 2,600 from ticket agents and 4,900 from Great Northern employees.

On January 16, 1951, Finley reported to Gavin that the judges decided that the best name submitted by ticket agents was “Evergreen.” Nine agents had entered that name, and the judges were unable to decide which of two had the best 25-word statement, so those two — Bert Neill of the Mr. Foster Travel Service in Los Angeles and Charles Munro, a Southern Pacific ticket agent in Oceano, California — each were awarded $500.

Among Great Northern employees, the judges decided the best entry was “Eight Stater.” Two employees submitted that name, but only one, Minneapolis station master Wallace Davis, included a 25-word statement, so he won the $500.

Despite the judges’ decisions, Gavin’s executive assistant, C.W. Moore, wrote the president on January 19 that, “We have not been able to settle on a name which we felt would be agreeable to you.” To keep options open, he attached more than 40 pages of submitted names that for Gavin’s review and advice. All of these pages, which include such amusing names as “James J. Hilliner,” “Glacier Glider,” “Aurora Borealis,” “General MacArthur,” and even “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” are included in the above packet of documents. Gavin immediately responded that, even though he still thought “Oriental” was a good name, that they could “go ahead and change the name to ‘Evergreen.'”

Yet just three days later, Moore replied that he thought “Western Star” — a name submitted by five employees and two ticket agents — would be a much better name. “WESTERN implies that the train runs through Western country” and “STAR connotes unusual quality,” argued Moore. Even though the railway was under no obligation to do so, he suggested that, if it selected that name, it give each of the seven people who entered it $100.

Strangely, a week later, on February 1, traffic manager Finley sent a memo to Gavin saying that, in consultation with Moore and Budd, “we are agreed that THE EIGHT STATER is an attractive name.” How could this be? Gavin already said he liked “Evergreen,” Moore said he didn’t like “Eight Stater” because it wasn’t “immediately associated with the West,” and Budd revealed later that “frankly I couldn’t be wholeheartedly in favor” of “Eight Stater” either. Not only was it not associated with the West, there were probably several trains in different parts of the country that served eight states, and technically trains 3 & 4 weren’t among them because they only went through 7 states (IL, WI, MN, ND, MT, ID, and WA), while the eighth state (OR) was only served by a connecting train that didn’t go by the name “Oriental Limited.”

It’s possible that internal rivalries influenced the debate over the name change. Gavin was nearing retirement age and both Finley and Budd were potential replacements. Budd had been a Great Northern employee until 1947, when he left the railway to become president of the Chicago & Eastern Illinois. He returned two years later when Thomas Dixon, GN’s operational vice president, unexpectedly passed away. Being the son of Ralph Budd, who was probably GN’s second-greatest president after James J. Hill, John Budd no doubt wanted the job of president, but it is possible that Finley considered Budd’s brief departure to the C&EI to be a sign of disloyalty.

In any case, Budd stepped into the debate on February 8 with a memo to Gavin noting that “The preliminary designs for tail signs for ‘The Eight Stater’ have arrived, and in going over them I have had some serious misgivings about the name.” He continued that “Mr. Moore’s suggestions of ‘The Western Star’ and ‘The West Wind’ appealed to me much more than ‘The Eight Stater'” and were even “preferable to ‘The Evergreen.'” On February 21, Finley capitulated and sent an uncharacteristically short note to Moore saying “I have talked to Mr. Budd and we are agreeable on ‘Western Star.'”

The name change was made official in a press release on March 14. Gavin retired in May, and — in what seems like a foregone conclusion today but may not have seemed so in 1951 — the board selected Budd to replace him. Thus it was John Budd who oversaw the inaugural departures of the new train on June 1.

Moore, the champion behind the name “Western Star,” retired in 1955. Finley continued as vice president of traffic until 1965. Budd, of course, stayed with the GN until the 1970 BN merger, and continued as chair of the BN board for a few years beyond that.

Although a political name such as “General MacArthur” would never be seriously considered, a letter written to GN on Western Star stationery revealed that even “Western Star” was a little bit political. The letter sardonically noted that “we, meaning of course only Democrats, have ‘given’ the Orient, which we never owned, to ‘Joe'” (i.e., Joseph Stalin). Nevertheless, the letter continued, “we [meaning America] can still be the Western Star.” Budd neutrally responded that “We went into the change in names with some misgivings and are glad to hear that you feel as you do.”

When introduced in 1951, the Western Star was far superior to the secondary trains of either the Milwaukee Road (the Columbian) or Northern Pacific (the Alaskan), easily the equal to the Milwaukee’s premiere Olympian Hiawatha, and arguably superior to Northern Pacific’s North Coast Limited. Great Northern, of course, continued to operate the Star right up until Amtrak took over in 1971. In the end, it appears that Finley was right that the train benefitted from a new name and Moore was right that “Western Star” was the best choice.