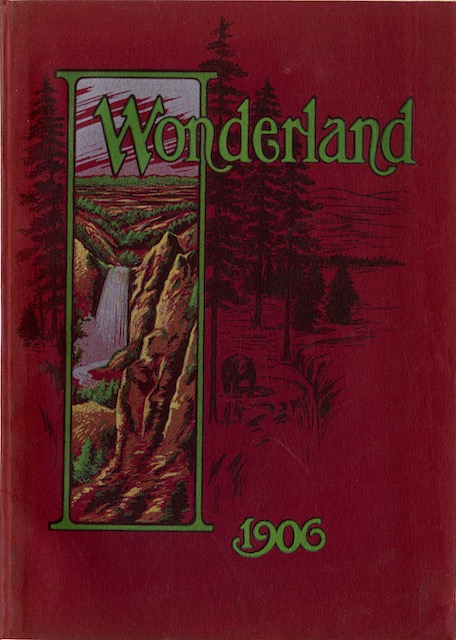

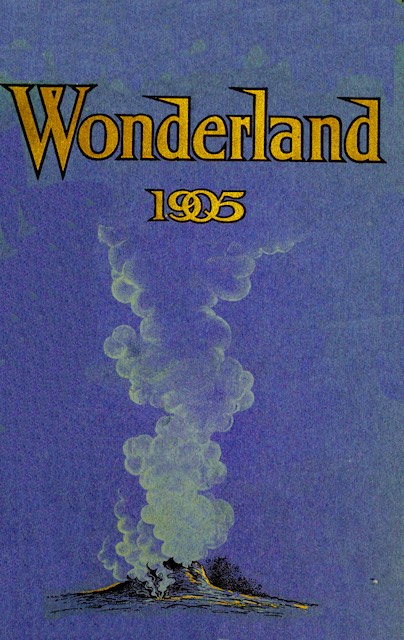

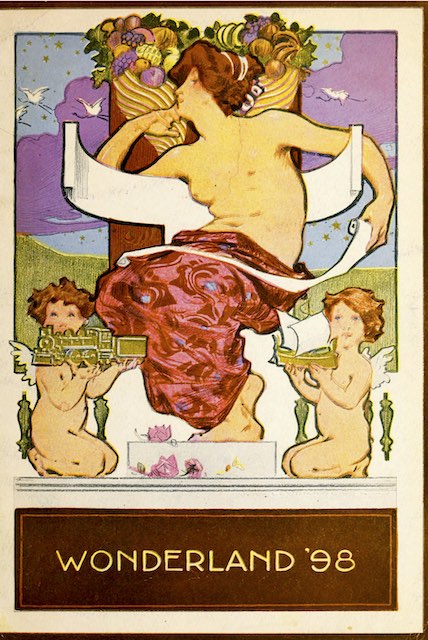

We’ve previously seen booklets of this title dated 1909 1915, and 1929. This one is from 1906, but wasn’t the first in the series as I’ve seen references to earlier editions in some of NP’s other publications. The booklet, which NP sold for a nominal 6¢ (presumably to cover postage; 6¢ in 1906 was a little more than $2 in today’s money) was designed to entice people in California to use the Northern Pacific on their eastward journeys, which required that they first take the Southern Pacific to Portland.

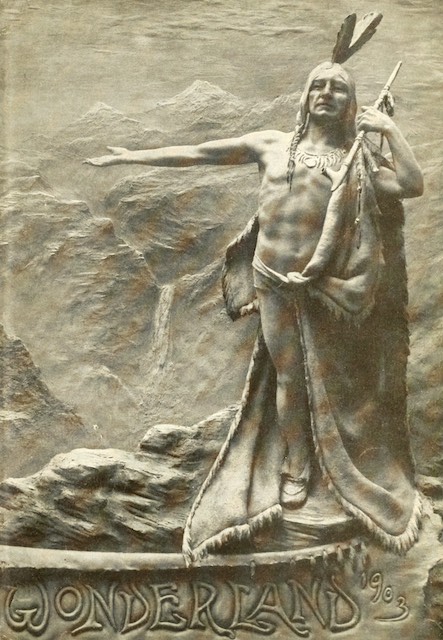

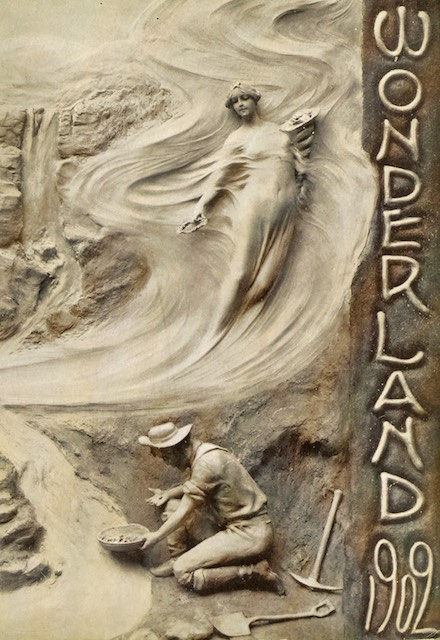

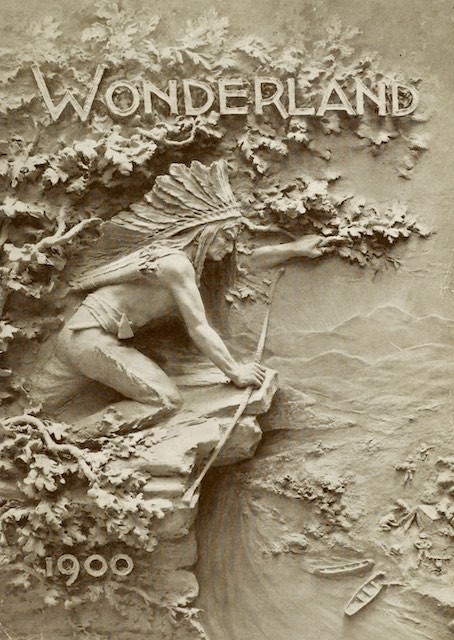

Click image to download an 25.6-MB PDF of this 60-page booklet from archive.org. Although I’ve edited the covers to restore their original colors, if you have a slow internet connection or are short on disc space, you should download archive.org’s version as the PDF is smaller than mine.

Click image to download an 25.6-MB PDF of this 60-page booklet from archive.org. Although I’ve edited the covers to restore their original colors, if you have a slow internet connection or are short on disc space, you should download archive.org’s version as the PDF is smaller than mine.

As was typical for early 20th century advertising, the booklet is a travelogue describing the wonders people would see and side trips they could take on such a journey. The first 6 pages describe the Southern Pacific’s coast route, while the next 9 focus on the Shasta route. Northern Pacific doesn’t begin until page 20, including a ferry ride across the Columbia River as the railroad bridge wouldn’t open until 1908. The booklet reaches St. Paul on page 42, but Yellowstone was given its own four-page chapter beginning on page 43. Continue reading