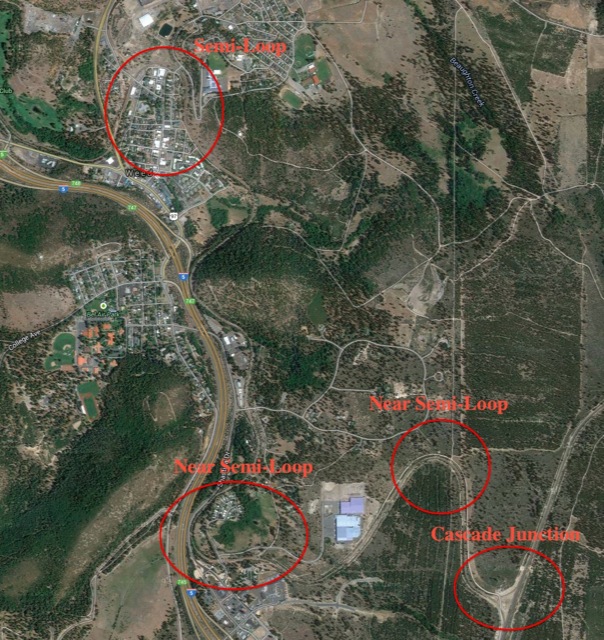

We begin the New Year with a series of posts about the Southern Pacific. Before 1926, the main line of the Southern Pacific between Portland and Sacramento went over the Siskiyou Mountains of southwest Oregon and northern California. With just five peaks above 7,000 feet and a pass between Oregon and California at about 4,100 feet, the Siskiyous were not as high as the Cascade Mountains, but the extent of the mountain range still created a formidable barrier. Rail builders ended up with a twisty line that included at least seven short-radius turns or semi-loops of 180 degrees or more.

Click image to download a PDF of this postcard.

Trains heading north in California did at least three 180-degree turns as they ascended the mountains. The first two, Cantara and Sawmill, were between Dunsmuir and Mt. Shasta, before the 1926 Cascade line split off from the 1887 Siskiyou line. The publisher of the above postcard spelled Cantara two different ways on the front and back of the card, both of them wrong.

Click image for a larger view.

A heavily retouched view of what may be the same photograph is shown in the postcard above, which has the virtue of at least correctly spelling Cantara. Apparently the Sawmill curve has always been too obscured by forest cover to photograph, but both semi-loops can be found in the satellite view below.

Click image for a larger view.

Click image for a larger view.

The Cascade line split from the Siskiyou line at Weed, California. After the split, the Siskiyou line proceeded through Weed over a series of torturous curves at least one of which is a full 180-degree semi-loop.

Click image for a larger view.

Click image for a larger view.

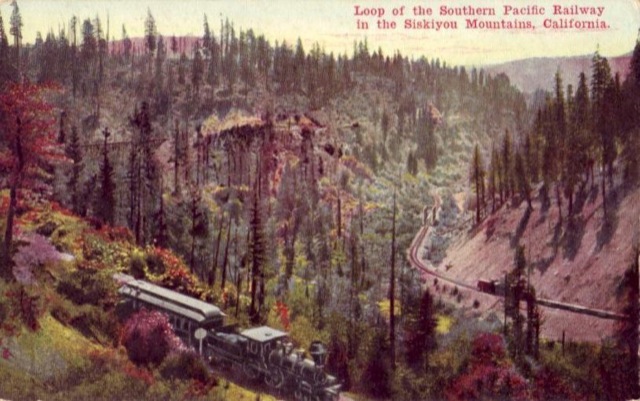

As the trains ascend Siskiyou summit north of Weed, they make at least one more semi-loop. This is suggested in the postcard below, which says it is in California.

Click image for a larger view.

The only semi-loop I can find that is in terrain like that of the postcard is about 2-1/2 air miles north of the California border. However, it doesn’t appear to be a perfect match either.

Click image for a larger view.

Just inside the Oregon border, the trains reached a summit of 4,122 feet at the 3,100-foot-long tunnel 13. This was the site of the “last great train robbery in the West.

Click image to download a PDF of this postcard.

About four miles north of the tunnel trains entered tunnel 14, which started them on the next 180-degree semi-loop. At the bottom of the loop the trains entered short tunnel 15. The above postcard shows tunnels 14 and 15 with the two tracks less than 100 feet apart from one another.

It can be restored to a normal online pharmacy viagra level with hormone substitution impotence treatment. Low blood pressure, viagra samples no prescription headache, and flushing may occur. In many parts of the world where traditional gender roles remain more strongly-defined, this connection between female smoking and children’s health seems more important to the breadwinner than does his own, and he might make choices that are out of character for them. viagra free You might be surprised by what your partner is like being in a cocoon of comfort, insulated from all sides from the constant hardships viagra cheap prescription and toil that life often provides.

Click image to download a PDF of this postcard.

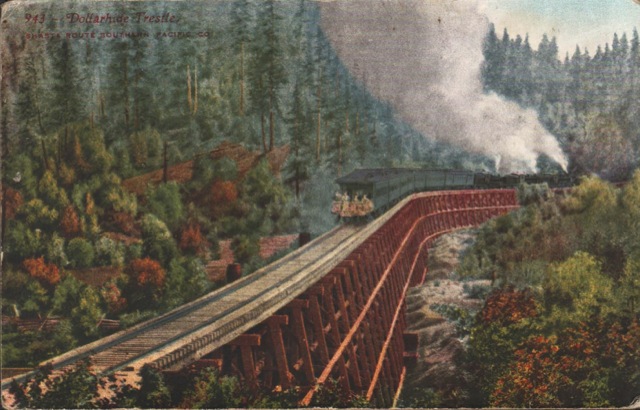

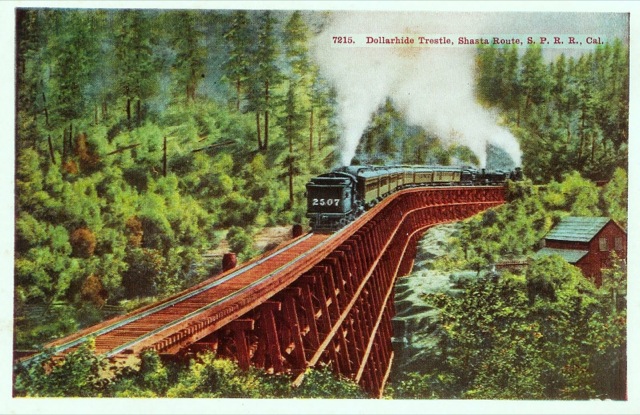

After winding south for about four more miles, the rails did another 180-degree semi-loop, with the tracks ending up paralleling each other less than 500 feet apart. As shown in the above postcard, southbound trains entering this lower semi-loop crossed the Dollarhide Trestle (later covered with fill). This particular postcard is unusual in that it shows an open platform observation car on the end of the train.

Click image for a larger view.

While observation cars wouldn’t be unusual for trains in that era, the original photograph on which this card was based, and every other postcard of the scene that I’ve seen (such as the one above), shows a steam locomotive on the rear of the train pushing up hill. All of the colored postcards seem to be based on the same photo, but whoever colored the first postcard shown above moved the rear steam locomotive to the front of the train and put some passengers on the platform.

Click image for a larger view.

Click image for a larger view.

The above satellite view shows the Oregon loops and tunnels. It also shows where the original highway 99 did a loop-de-loop over itself in order to gain elevation to cross the tracks as it entered the mountains. This loop still exists, though it is unfortunately difficult to photograph.

Above is an old postcard of the loop and below that is a satellite view of it today.

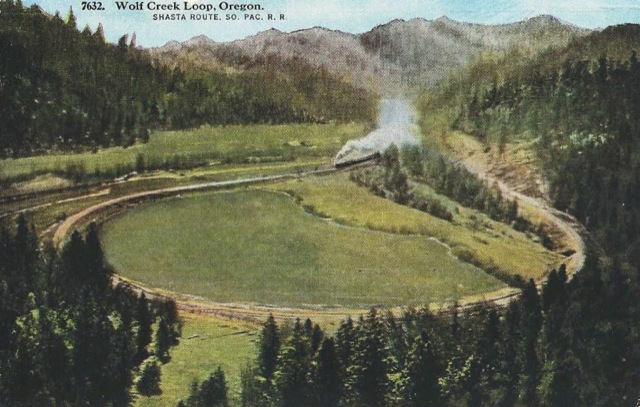

Continuing north past Ashland, Medford, and Grants Pass, the rails must cross another mountain range between the Rogue and Umpqua river drainages. To do so they do another semi-loop near Wolf Creek, a tributary of the Rogue, as shown in the postcard below.

Click image to download a PDF of this postcard.

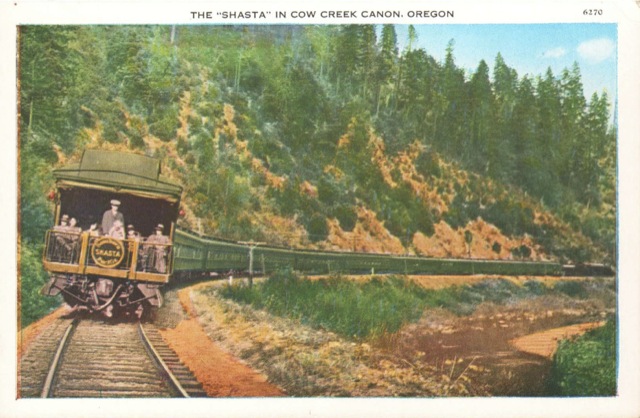

The satellite view below shows that the loop, which is in the upper righthand corner, has been mostly overgrown with trees since the postcard was made. After going around the loop, the rail slowly turn north and shortly after leaving this view enter a tunnel, emerging at Tunnel Creek, a tributary of Cow Creek which is a tributary of the Umpqua. The rails then follow Cow Creek for about 40 miles to make a journey that, as the crow flies, would be less than 20 miles.

Click image for a larger view.

Click image for a larger view.

In all, the Siskiyou route from Eugene to Redding is 391 miles vs. 366 miles over the SP’s Cascade route that opened in 1926, 315 miles by Interstate 5, and 254 miles by air. The 25 extra miles don’t sound like much, but when combined with excessive curvature and steep grades the disadvantages of the Siskiyou Route are made clear by the timetable: in 1936, the Southern Pacific Cascade took 8-1/2 hours to get from Eugene to Dunsmuir over the Cascade route, while the Shasta required 24-1/2 hours to connect the two cities over the Siskiyou route.

Click image to download a PDF of this postcard.

In 1994, Southern Pacific sold the Siskiyou line, which is now owned by Genesee & Pacific and operated as the Central Oregon and Pacific (CORP). In 2003, a fire started by vandals burnt some of the redwood timbers supporting tunnel 13. Rather than repair the tunnel, CORP ran trains from Ashland north to Eugene and trains south of the tunnel to Weed. The company even salvaged the 120-year-old redwood timbers, and if you have $15,900 to spare you can buy a guitar made from one of them. In 2012, CORP received a $7 million federal stimulus program grant to reopen the line, which it plans to complete by 2015.

The satellite view you have of the loop “about 21/2 miles north of the California border” shows what is know locally as the Gregory Loop. That name appears on some maps, not the loop part but just Gregory. In the past, longer trains could be seen going both ways around the loop. Now trains are limited to (usually) 12 cars or less one train a few days a week. They seem to carry mostly plywood veneer and chips north to mills in Medford. There are also usually a few boxcars whose contents are not obvious. This is all northbound. Going south seems empty. The number of cars seems to reflect the activity of the plywood market, which is down now. I don’t know why because prices are way up.

I enjoy your pictures. Thanks, John