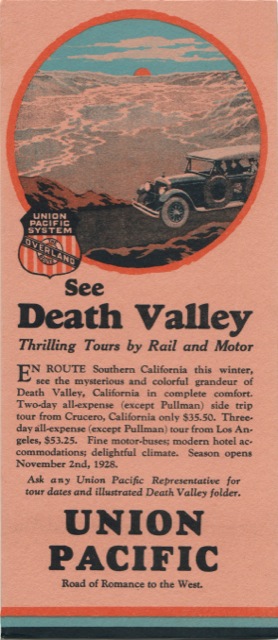

Most western national parks had short seasons of around June 15 through September 15. But Union Pacific could offer a winter destination as well: Death Valley, which had a “delightful climate,” at least after November 2, when the 1928 season opened. Death Valley became a national monument in 1933 and a national park in 1994, but until 1927, the year before this blotter was printed, it wasn’t anything but a dry spot on the map a few miles from UP’s Salt Lake-Los Angeles line.

Click image to download a PDF of this blotter.

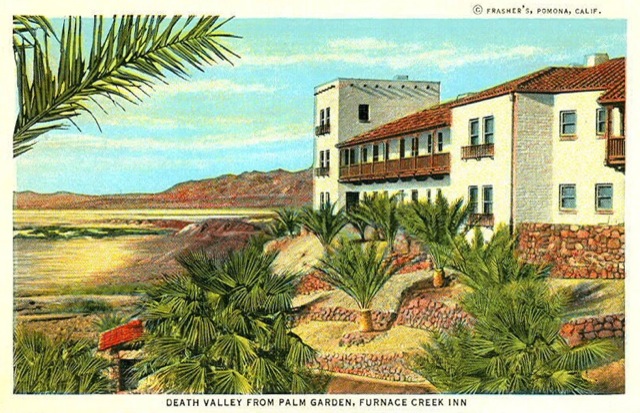

Before it was a destination resort, Death Valley was a source of borax. In 1927, Pacific Borax turned one of its crew quarters into the Furnace Creek Inn and began lobbying to have the area made into a national park. Union Pacific brought passengers to the area and they traveled to the inn on buses that served Bryce Canyon in the summer.

Click image to download a PDF of this Union Pacific postcard.

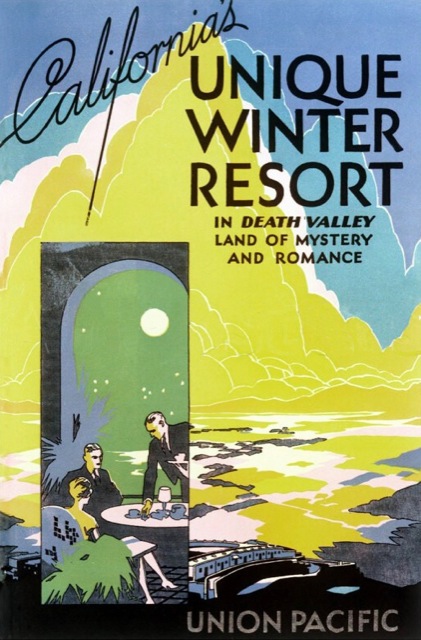

Union Pacific published a Death Valley travel booklet in 1929. I don’t have a copy, but below is the cover.

Click image for a slightly larger view.

Park Service director Stephen Mather wasn’t enthused about the idea of turning Death Valley into a national park. Some say it was because he once worked for Pacific Borax and he didn’t want to create an appearance of a conflict of interest, but he also believed that only areas of unique national significance should be national parks, and he actively lobbied to turn at least one park over to the state in which it was located. Mather’s successor, Horace Albright, was an empire builder who took a much more expansive view of what could be included in the National Park System, and he happily persuaded President Roosevelt to designate Death Valley as a national monument in 1933.