A full-page ad on the inside back cover of this timetable highlights the “Rock Island States of America,” fourteen states served by that railroad. This reminds me that the Rock Island and the Burlington were very similar railroads serving largely the same territory. An objective look at just their routes in the mid-1950s might make one conclude that, if one were to survive and other disappear, it would have been the Rock Island that survived and the Burlington that would disappear.

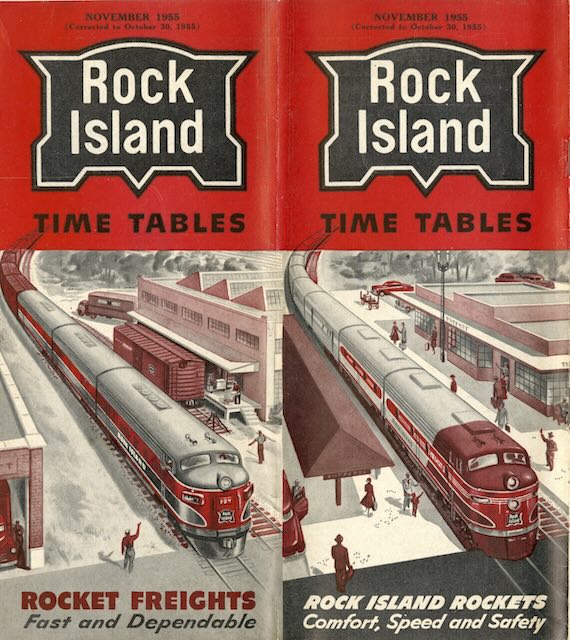

Click image to download an 19.5-MB PDF of this 36-page timetable.

Click image to download an 19.5-MB PDF of this 36-page timetable.

Both served the same core states: Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, and Texas. Both also reached a corner of New Mexico and one end of South Dakota. Rock Island had a strong network in Kansas while Burlington reached Kansas only on a couple of minor branch lines. Rock Island went to Memphis, Tennessee while Burlington went to Paducah, Kentucky.

Rock Island also served Arkansas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma while Burlington also went to Wyoming and Montana. But Rock Island’s network in these three southern states was much stronger than Burlington’s in the two Rocky Mountain states. Rock Island connected Dallas and Houston with Kansas City and Chicago while Burlington only connected them with Denver and (through partner railroads) Seattle.

Burlington definitely had better routes for passenger service in some corridors. One of the most competitive corridors in the country was Chicago-Twin Cities, but Rock Island wasn’t part of that competition because its route was too long. Chicago-Denver was also hotly competitive, but again due to its inferior route Rock Island took a distant third place after Burlington and UP. But freight was the source of most railroad revenue and exact routes were less important to freight than to passengers.

What the Burlington had that Rock Island didn’t was owner-partners. Great Northern and Northern Pacific each owned almost half of the Burlington and that gave the railroad confidence to respond to its customers and not to Wall Street. Rock Island, meanwhile, tried to boost its stock price by deferring maintenance and drove itself into oblivion.

Rock Island has been called “one railroad too many,” which might have proven true in the deregulated world of the 1980s but certainly wasn’t obvious in the 1950s. Unfortunately, the railroad didn’t survive past 1980 to find out.

Meanwhile, the confusion in the 1952 timetable about the “Diesel Electric Car” offering coach service between Memphis and Oklahoma City but unspecified service between Oklahoma City and Amarillo has been cleared up in this edition. This one uses the more common term (for a Budd vehicle) “Rail Diesel Car” and specifies that it goes all the way from Memphis to Amarillo. The lack of sleeping cars is only slightly remedied by a note saying that “pillows available” on the overnight portion between Oklahoma City and Amarillo.

There were probably two railroads too many: The Rock and The Milwaukee Road, while at the same time CNW wasn’t doing so great itself. In 1955 UP moved the City streamliners from CNW to Milwaukee, because (a) the track between Chicago and Omaha was in bad shape, and (b) CNW had run up a car usage debt of over $1 million, which they could not ever be expected to repay. Dollars and cents aside, UP management probably felt they could not risk the bad publicity a high speed derailment of one of the City trains would bring.