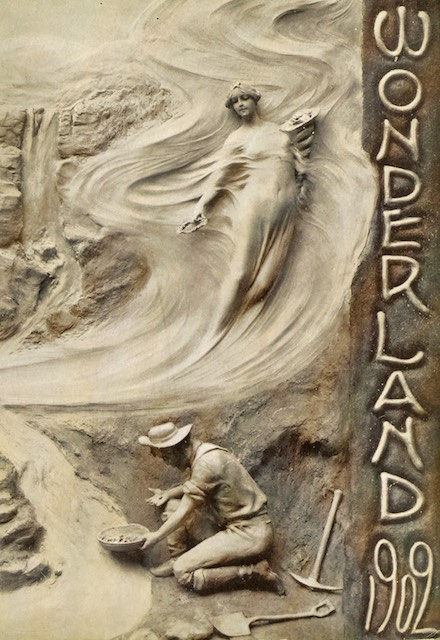

The cover art on Wonderland 1900 and Wonderland 1901 was unsigned, but the 1902 edition is signed “Alfred Lenz N.Y.” The incisions in the clay make it clear that these are sculptures, not simply trompe l’oeil paintings.

Click image to download a 41.6-MB PDF of this 112-page booklet.

Click image to download a 41.6-MB PDF of this 112-page booklet.

Born in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin in 1872, Lenz apprenticed to a watchmaker and jeweler in Milwaukee at the age of 15. Deciding to make metal sculpting his life’s work, he studied in San Francisco and Europe before settling in Flushing, New York, where he specialized in lost wax castings. With lungs damaged by years of breathing acid fumes, he died of heart failure at the young age of 54.

Most of what I can learn about Lenz comes from some papers contributed to the Smithsonian by Sara Rockefeller Currie, who described herself as his assistant and the model for at least one of his sculptures. The papers, which the Smithsonian dutifully records as being 0.01-feet (about 3 millimeters) thick, consisted of several photographs of Lenz and a short biography.

One of the photographs is inscribed, “The most important man I’ve ever met – S.B. Rockefeller.” Since she was supposedly a member of the Rockefeller family (though I can’t find her on any Rockefeller family tree), she must have met a lot of important people. Although she must have been married to someone named Currie, this makes me suspect she was more than just an assistant to Lenz.

The two met in 1899, when Lenz was 27 years old and just getting started in his artistic career. That’s also when he did the cover art for Wonderland 1900, which is clearly in clay and not the metal work for which he later became known. Two different sculptures were used for the front and back covers of Wonderland 1900, while the 1901 through 1903 editions consist of just one sculpture that wrapped around the front and back covers. Each edition also has an average of about six additional sculptures for the interior chapter headings.

While the front cover of Wonderland 1900 portrayed an Indian looking down on members of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, the back cover contrasted this with a then-modern view of a train passing a city, which was appropriate as Wheeler’s lengthy article about Lewis & Clark contrasted the trails they went on with the improvements made since that time. The locomotive in the sculpture was a 2-6-0 numbered 185, which had been built to haul freights but was shown by Lenz pulling a passenger train (which it probably did from time to time).

The cover of the 1902 edition shows a diaphanously robed woman holding what is undoubtedly meant to be a gold crown over the head of a miner panning for gold. Clearly, this symbolized the wealth Americans could gain by traveling west.

“The leading chapter of this number tells the story of mining in Montana from the early days to the present,” says the title page, making the cover particularly appropriate. “Other chapters describe the Northern Cheyenne Indians, Yellowstone Park, the Puget Sound Country, etc.” The “etc.” is an article about glacially-carved lakes in Minnesota, which is in fact the leading chapter of the booklet, not the article about Montana mining.