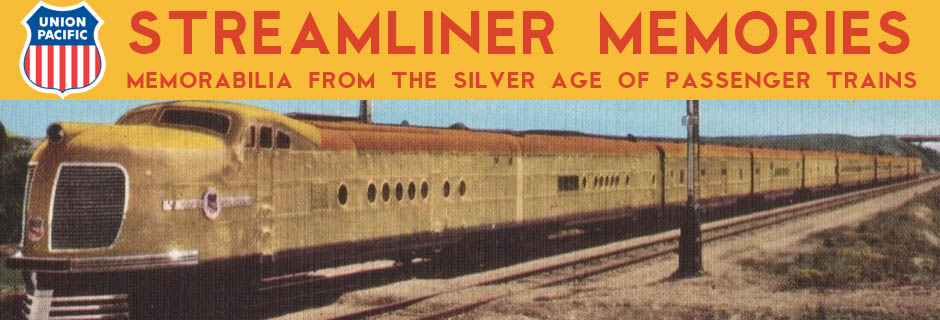

The year 1956 was the most momentous in the history of passenger trains since the original Zephyr and M-10000 were introduced in 1934. Not two, not three, but a total of five new kinds of trains were introduced to the American public in 1956, with two more in early 1957. The first and most famous of these was the General Motors Aerotrain.

Click image to download a 3.3-MB PDF of this brochure.

With five new trains (seven including the two in early 1957), 1956 could have been even more momentous than 1933, except for the fact that four of the seven trains were such miserable failures that they remained in service for less than two years. Two others were only partial successes: one operated for about a decade, while the other stayed in service, but in heavily modified form, for more than two decades.

F-86 Sabre jet fighter, stylistic inspiration for. . .

The one unqualified success was the hi-level El Capitan, whose cars were lighter per passenger than ordinary trains but still much heavier overall. The other six trains attempted to follow the Talgo train example of being both super lightweight and low to the ground.

. . . the 1951 LeSabre concept car, which in turn was the stylistic inspiration for. . .

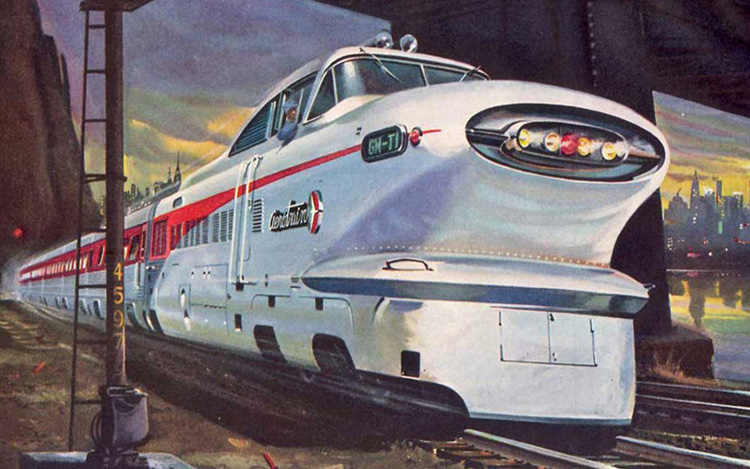

General Motors thought that it could use its expertise in styling and mass production to improve on the Talgo train’s concept of lightweight cars on two-wheel trucks. Most of the Aerotrain’s styling was in the locomotive, which designed by Charles Jordan, who later designed the 1958 Corvette and eventually became chief of design for Cadillac.

. . . the Aerotrain. Click image to view the General Motors ad for the train that was in the December 10, 1955 issue of Saturday Evening Post from which this illustration was taken.

Like the F-86 Sabre and the 1951 LeSabre, the LWT-12 (lightweight 1,200-hp) locomotives had a turret cab. Like the car, what appeared to be the air intake for the jet engine was actually used for the locomotive headlights.

The LeSabre headlamps were hidden in the “air intake.” Note that this is just a LeSabre, not a Buick LeSabre, the first of which came out in the 1959 model year.

The rear of the train was not quite as imaginatively styled, and looked a lot like the rear of a 1955 Chevy or Pontiac station wagon. Instead of a separate baggage car, large bags could be stowed in compartments underneath the passengers, just like a Greyhound bus.

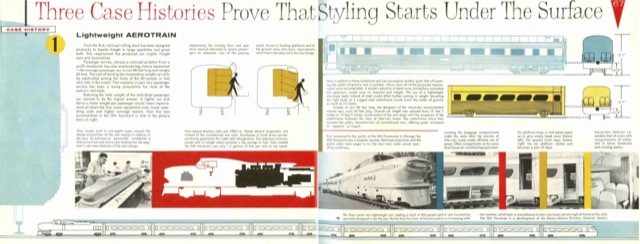

The mass production aspect of the train was that each of the ten cars were basically Greyhound bus bodies on steel wheels instead of rubber tires. Unlike the Talgo trains, the cars were not articulated, meaning each car had its own four wheels. But they were definitely light weight, and GM bragged that two of its cars weighed half as much as an ordinary coach but carried as many passengers. Moreover, the company claimed the train cars cost only about $1,000 per seat, compared with costs closer to $3,000 per seat for ordinary trains.

Moreover, said the company, the cars would be easy to refurbish. While the undercarriage was expected to last many years, passenger car interiors wore out quickly. When that happened, GM proposed to simply remove the entire body of the car from the undercarriage and replace it with a new one fresh from the factory. This would cost a lot less, the company claimed, than tearing out and replacing seats, carpet, and other interior fixtures.

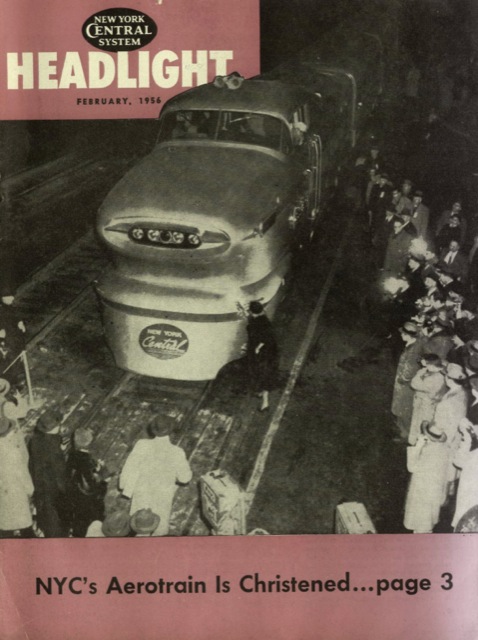

Click image to download a 10.6-MB PDF of this New York Central magazine featuring an article about the Aerotrain.

General Motors built two ten-car Aerotrains and talked several railroads into testing them. On January 5, 1956, one Aerotrain made a test run from Washington to Newark on the Pennsylvania; while the other dashed from Chicago to Detroit on the New York Central in four hours–more than an hour faster than Amtrak’s fastest train on that route today. After a few more press runs, the Pennsylvania tried to put an Aerotrain into regular service between Washington and New York on February 6, but the train was withdrawn after one day to reduce the noise levels in the cars.

General Motors was booming in the 1950s, having made its 50 millionth automobile in 1954 and on its way to make another 50 million in the next 13 years. Part of its success was owed to Harley Earl, whose styling section designed cars, buses, trains, and other GM products. These two pages are from The Look of Things, a booklet about the styling section. Click image to download a 17-MB PDF of the entire booklet.

In late February, the Pennsylvania agreed to rent one Aerotrain at $250 a day to operate between New York and Pittsburgh on a 7.5-hour schedule–the fastest ever on that route. In March, the other train did demonstration runs on the Chicago & North Western, Great Northern, Illinois Central, Santa Fe, Southern Pacific, and Union Pacific. None of the railroads were happy with the ride quality. In late April, the train was put into revenue service between Chicago and Detroit on a 4:20 schedule, which was still 40 minutes faster than the fastest train at the time.

This drawing was done by Will Anderson. Click the image for a larger view; click here for a drawing of the complete 10-car train; click here to see more of Anderson’s Aerotrain drawings.

In June, however, the Pennsylvania cut back its New York-Pittsburgh Aerotrain to just Philadelphia-Pittsburgh. From July 15 to October 27, 1956, the New York Central ran its Aerotrain between Chicago and Cleveland instead of Chicago and Detroit. Starting on December 18, Union Pacific took the one that had been on the New York Central to run between Los Angeles and Las Vegas. The other train continued to run between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh until June 29, 1957, after which it joined the Union Pacific train in City of Las Vegas service. However, that lasted only until October 27, 1957.

The Pennsylvania Railroad was proud enough of its Aerotrain that it commissioned Grif Teller to paint it for its 1956 calendar.

All the railroads that tested Aerotrains came to the same conclusion: whether in short-haul or long-haul service, the Aerotrains were awful. The ride was uncomfortable, particularly at high speeds, and the 1,200-hp engines weren’t powerful enough to get up hills such as the Sorrento grade outside of San Diego or Cajon Pass east of Los Angeles without helpers.

The City of Las Vegas Aerotrain at Cajon Pass, probably just after the helper locomotive cut off.

In October, 1958, General Motors sold both trains to the Rock Island Railroad, which used them in commuter service between Chicago and Joliet. Although the railroad hoped its passengers wouldn’t be too uncomfortable at the lower speeds of a commuter train, both trains ended service in 1966. Most of the cars were scrapped, but one of the locomotives is now in the National Railroad Museum in Green Bay and the other plus two cars are in the National Museum of Transportation in St. Louis.

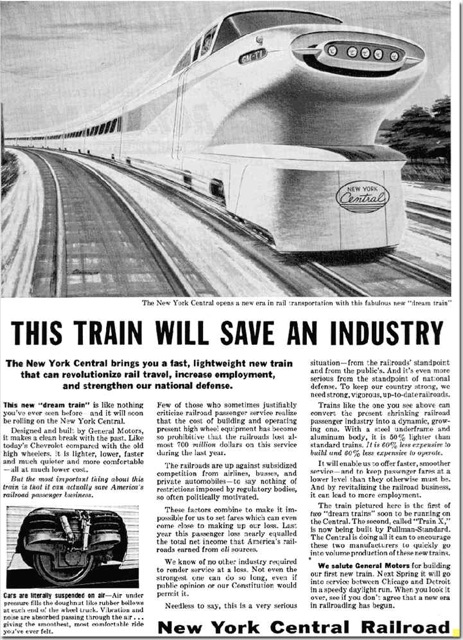

This New York Central ad predicting that the Aerotrain would save the rail passenger industry turned out to be sadly mistaken. The train operated on the New York Central for only a few months before the railroad returned it to GM.

This New York Central ad predicting that the Aerotrain would save the rail passenger industry turned out to be sadly mistaken. The train operated on the New York Central for only a few months before the railroad returned it to GM.