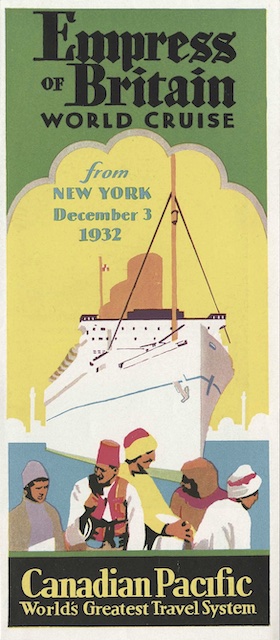

Leaving New York on December 3 and returning on April 11, the 1932-33 world cruise was 129 days long, two days longer than in 1931-32. The first 20 pages of the booklet below re-introduces us to the new Empress of Britain, including some rooms not shown in the introductory booklets. A library had walls of Circassian Walnut (but no bookshelves; apparently it was more of a writing room than a reading room). A movie theater was fully equipped to show “talkies.” Turkish baths aren’t shown but, the booklet says, were “decorated in marble and silver.”

Click image to view and download a 73.9-MB PDF of this booklet from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

Click image to view and download a 73.9-MB PDF of this booklet from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

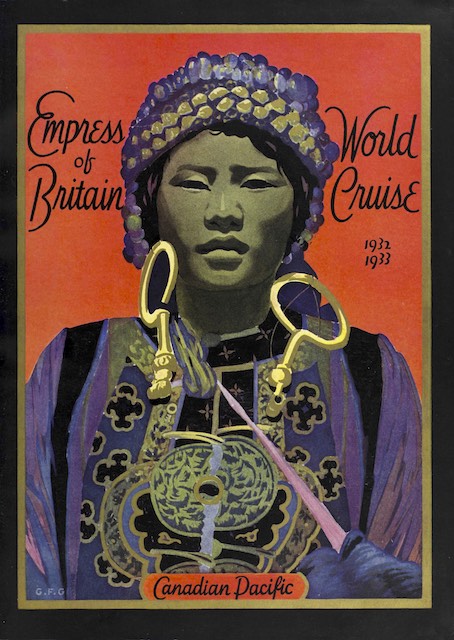

The cover of the booklet is signed GFG, meaning Gordon Fraser Gillespie, one of Canadian Pacific’s staff artists. He first began working on commission for CP in 1913 and in 1948 was placed in charge for all commercial art for the railroad. At some point between those two years he began working for CP full-time. I’ve previously stated that I suspect he and/or Charles James Greenwood, another staff artist, contributed many of the paintings to the 1926-27 world cruise booklet without getting any credit. I’m glad he got credit for this one.

After presenting the ship, the rest of this 68-page booklet describes the cruise. Instead of brightly colored paintings, the various ports are illustrated with black-and-white photos that no doubt were taken on previous cruises. This is likely an economy measure reflecting the Depression as printing in one color (black) costs less than several, especially since in those days the four-color process was not well developed so reproducing paintings usually required seven or more imprints rather than just the four we make today. We’ve previously seen the page 48 photo of a hula dancer on the cover of a 1934 menu.

Click image to view and download a 4.7-MB PDF of this brochure from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

Click image to view and download a 4.7-MB PDF of this brochure from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

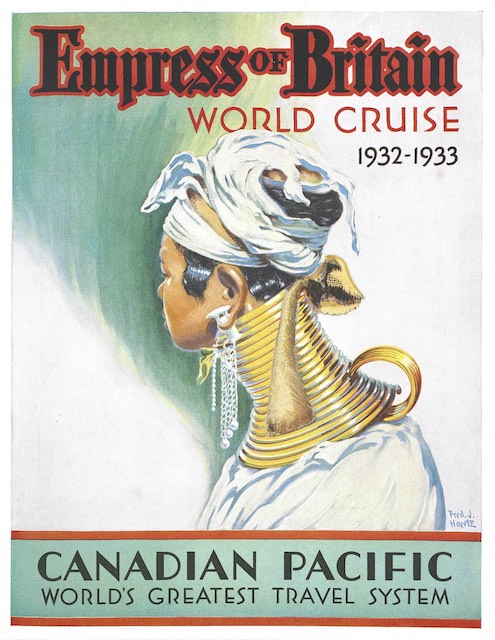

The cover painting on the above brochure, which shows the Empress of Britain deck plans, was done by Fred Hoertz. He was a New York maritime artist who painting most of the ocean liners that entered New York harbor. He also painted a couple of ships for Canadian Pacific that were used in a 1930-31 world cruise brochure. It is somewhat surprising to see him paint a non-maritime subject.

Click image to view and download a 6.8-MB PDF of this brochure from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

Click image to view and download a 6.8-MB PDF of this brochure from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

Canadian Pacific made many adjustments to the fares for the 1932-33 world cruise. As I previously noted, the average fares collected from the 1931-32 cruise were well below expectations. To fix this, CP reduced the fares for most of the upper-deck rooms by 6 to 10 percent. Meanwhile, it increased the fares for the lower-deck rooms by 10 to 15 percent. Apparently its goal was to make the more expensive rooms more attractive and thus boost the overall average fare.

Click image to view and download a 3.6-MB PDF of this booklet from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

Click image to view and download a 3.6-MB PDF of this booklet from the University of British Columbia Chung collection.

The new pricing strategy didn’t work. While I don’t know how much CP collected in total revenues from the cruise, the total number of passengers declined by 29 percent, from 379 in 1931-32 to 283 in 1932-33. Worse, fewer than 190 attended the entire cruise; about 100 only went as far as India. The number of servants remained the same at 11, suggesting that the wealthiest customers were somewhat insensitive to prices and the Depression. By lowering the prices of the more expensive rooms, CP may have actually reduced the average fare collected from all of the passengers. Certainly, this was the worst-attended world cruise ever offered by Canadian Pacific.

A few notable names appear on the list of passengers. Baron F. De Marwicz (1907-1990) was born in Germany as Friedrich Alfred von der Marwitz, but his family changed the name to Marwicz when they moved to England. Known as Frank, he was an accomplished hockey player who played on England’s national team in 1930 and 1934 world championships. He was accompanied on the cruise by his wife, Baroness Diana Frances De Marwicz née Walkington, a native of Yorkshire. I suspect that Marwicz’ title comes from Germany, not England.

Sir Walter Preston (1875-1946) was an engineer who designed railway and steamship equipment and had 35 patents to his name. He was also a member of the British parliament from 1918-1923 and 1928-1937. He apparently received his knighthood for his service in parliament that ended in 1923.

The most famous name on the list was George Bernard Shaw, whose wife, Charlotte, particularly enjoyed ocean voyages. He spent much of his time in his apartment writing, skipping the excursions at many of the ports.

Another familiar name on the cruise, at least to North Americans, is listed as Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jr. In fact, he was Cornelius Vanderbilt IV, the great grandson of the founder of the New York Central Railroad. However, the Vanderbilt who was on this cruise did not get to enjoy much of his family’s riches.

After serving in the Great War, “Junior” decided to become a newspaper owner. This raised the ire of his parents, who hated journalists, and they disinherited him. The fact that he lost $2 million on the newspapers he bought didn’t help. Ironically, his father had also been mostly disinherited from his family for marrying beneath him. Despite being disinherited, Junior continued to live the high life, marrying seven times and going heavily into debt to do things such as world cruises. He was 33 at the time of this cruise and between marriages, though there were on-board rumors of a romance between him and a 19-year-old passenger named Adonnell Massie.