Competition between Chicago and San Francisco was much less intense than in the Los Angeles corridor mainly because the Overland Route was by far the shortest route. In 1911, when Western Pacific began serving this corridor, the Overland Route was 2,271 miles; the Santa Fe was over 300 miles more at 2,578; and the Burlington-Rio Grande-Western Pacific was another 100 miles more at 2,680.

The Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul considered itself competitive enough with the C&NW that anyone trying to choose between them would face a “crisis.” Click image for a larger view of this ad from 1903.

As previously noted here, in the early 1870s, passengers could expect to spend around 107 hours getting from Chicago to San Francisco on the Overland route. The only real competition was between Chicago and Council Bluffs, where the St. Paul road vied with the Chicago & North Western for passengers connecting with the Union Pacific.

In 1889, Union Pacific talked C&NW and Southern Pacific into running a through train, the Golden Gate Special, which was described here previously. The all-Pullman train took 82-1/2 hours from Chicago to San Francisco (including the ferry ride from Oakland). This train only operated a single season, while the other main train, the Pacific Limited, took 87-1/2 hours.

Around that year, Santa Fe began operating Chicago-San Francisco through cars. Passengers would first ride the Chicago, Santa Fe & California Railway to Kansas City. This was leased by the AT&SF, but coordination was poor enough that there were no through cars and a three-hour layover in Kansas City. There were through cars from Kansas City to San Francisco, but they would use Southern Pacific tracks from Mojave, California to the Bay Area. The entire trip required nearly 120 hours, which wasn’t even competitive with the Overland Route in 1872, much less 1889.

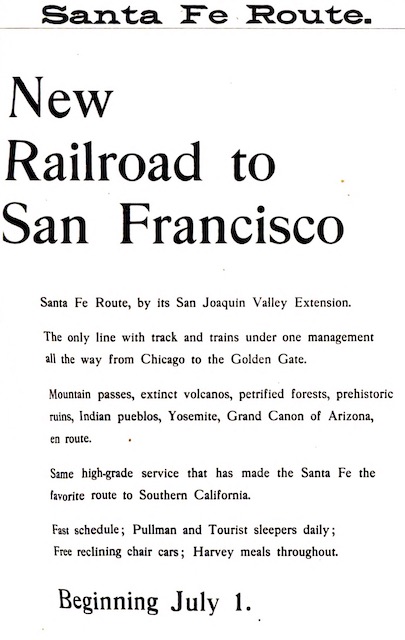

The Santa Fe was already pushing its “all the way” slogan in 1900. Click image for a larger view of this ad from the July 1900 Official Guide.

In 1900, Santa Fe proudly announced that it had finished construction of its own line to the Bay Area. This made it “the only line with track and trains under one management all the way from Chicago to the Golden Gate.” It still wasn’t very competitive: in that year, the Overland Limited was able to speed passengers to San Francisco in under 73 hours and UP’s secondary train took just over 86. Santa Fe’s initial entry took 94.

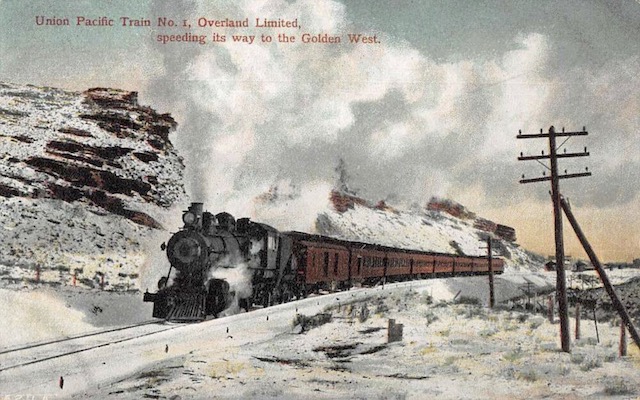

This Overland Limited postcard from approximately 1908 promises a speedy route to the Golden West. The locomotive appears to be a 4-6-0. Click image to download a 218-KB PDF of this postcard.

This Overland Limited postcard from approximately 1908 promises a speedy route to the Golden West. The locomotive appears to be a 4-6-0. Click image to download a 218-KB PDF of this postcard.

In November 1909, George Gould managed to complete the Western Pacific from Salt Lake to Oakland, thus enabling his Missouri Pacific and Rio Grande to provide through train service from St. Louis to the Bay Area. The new railroad promised through cars to Chicago over the Burlington. However, the first passenger train didn’t operate until August 17, 1910, and that was a special train for representatives of the press and various VIPs. I’m not sure when the first regularly scheduled passenger train began, but it wasn’t in August or September 1910, as the September Official Guide still routes Rio Grande trains over the Southern Pacific.

This July, 1910 Official Guide ad promises to introduce passenger service “early in August. Click image for a larger view.

In 1911, Burlington advertised that Chicago passengers could take its trains to Denver, the Rio Grande to Salt Lake, and either the Western Pacific or Southern Pacific to San Francisco, taking 95-1/2 hours either way. This wasn’t competitive as the Overland Limited was down to 72-1/2 hours and Union Pacific’s secondary train with the clumsy name of China & Japan Fast Mail was 90 hours. Santa Fe’s California Limited was under 87 hours and its San Francisco Express required 93-1/2 hours, making the Gould route slower than even the secondary trains of its competitors.

The problem was that the Rio Grande route required a detour south from Denver to Pueblo then up the Royal Gorge to Grand Junction before heading west to Salt Lake. As of 1926, the railroads running this route didn’t even try to compete on time, instead allowing a 2-1/2 hour layover in Salt Lake City so that passengers could “visit the principal points of interest,” such as the Mormon Temple and Tabernacle. While the Santa Fe and Overland routes were down to around 68 hours, the no-longer-Gould route required nearly 93 hours.

In 1929, the Overland Route carriers cut the Overland Flyer to 63 hours, which was the time of Santa Fe’s California Limited from Chicago to Los Angeles. Santa Fe was initially unable to match that, and Rio Grande-Western Pacific didn’t even try.

Locomotive 94 was typical of Western Pacific’s 4-6-0s except that it was present when the railroad pounded its last spike and hauled the first passenger train down the Feather River Canyon. For these reasons, WP considered it worthy of preservation and it is now in the Western Railway Museum in Suisan, California. Click image for a larger view.

It is likely a sign of financial stress that Western Pacific didn’t order new steam locomotives for its passenger service for two decades after it began. About 20 percent of its steam locomotives were 4-6-0s, which by 1911 were considered obsolete by most other railroads that were operating 4-6-2s and starting to think about 4-8-2s. Thanks to its gentle grades and probably also due to a lack of demand making for short trains, WP was able to make due with 4-6-0s at least through 1937.

Other than a couple that it inherited from another railroad, WP’s 4-6-0s had 67″ drivers, which obviously meant they weren’t going to try for high speeds. However, this allowed them to have tractive efforts of more than 29,000 pounds, which enabled the locomotives to pull passenger trains up the 1 percent grades of the Feather River Canyon.

In 1934, the Rio Grande completed the Dotsero cutoff, allowing it to run trains through the Moffat Tunnel rather than taking the lengthy detour through Pueblo and the Royal Gorge. However, through passenger trains didn’t begin using this route until June, 1939, with the introduction of the Exposition Flyer.

To handle the anticipated traffic on the Flyer, Western Pacific bought some used 4-8-2 locomotives from the Florida East Coast Railway. These produced more than 44,000 pounds of tractive effort on 73″ drivers, allowing for a little higher speeds and much longer trains.

Thanks in part to these locomotives, the railroads were able to run the Exposition Flyer from Chicago to San Francisco in about 60 hours, making it competitive with the Overland Limited. In fact, the CB&Q/RG/WP route was 10 minutes shorter, being 59 hours and 55 minutes while the Overland was 60 hours and 5 minutes.

While 10 minutes was trivial, the real question was whether people would give up the exclusivity of the Overland Limited for the scenery of the Exposition Flyer, and the answer, in a lot of cases, turned out to be yes. Of course, the Overland Route was also the home of the City of San Francisco, which made the trip in under 40 hours, but in 1939 it only went once every six days.

This left the Santa Fe in an unexpected third place. Santa Fe patrons who wanted higher speeds could take the Chief to Barstow and another train to San Francisco, making the trip in 58-1/2 hours. However, there were no through cars on this route, so those who wanted to sleep in on their final day on the train would have to take the California Limited, whose through cars to San Francisco took more than 71 hours. The Santa Fe wouldn’t attempt to rectify this until it introduced the San Francisco Chief in 1954, and even then it remained an also-ran behind the City of San Francisco and California Zephyr.

When it was inaugurated in 1854, the San Francisco Chief was intended less as a point-to-point Chicago-SF service than an attempt to connect city pairs such as Houston – Oakland, Chicago-Phoenix, and Dallas-Los Angeles. Especially by the late 1950s with SP having turned on its old friend the train traveler, if you wanted to travel from Houston to the Bay Area, what would your choice be, the Sunset with a layover in L.A., or a through sleeping car on Santa Fe?