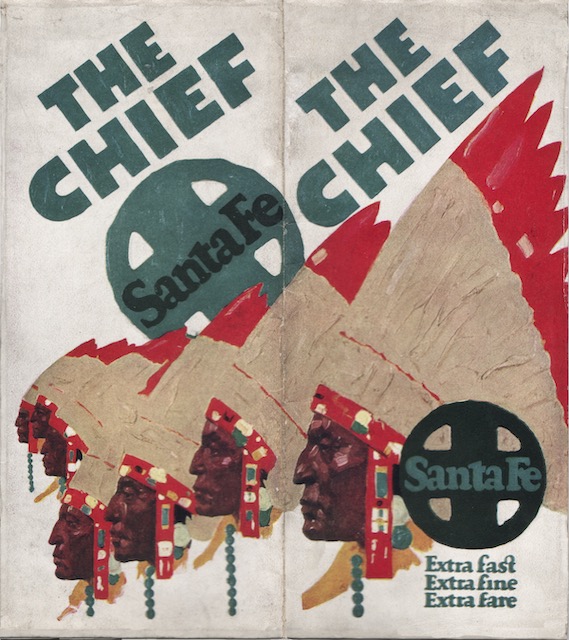

On November 14, 1926, after eight winters of not running the de Luxe, Santa Fe inaugurated the Chief. Significantly, the railway didn’t include the word “limited” in the name, hinting that this train, like the de Luxe, was even better than a limited. “The Chief is frankly designed for people who want the best,” says this booklet, which was published a few weeks after the inaugural run.

Click image to download a 7.4-MB PDF of this 28-page booklet.

Click image to download a 7.4-MB PDF of this 28-page booklet.

This booklet was published in December for the train’s first “season,” a throwback to the de Luxe that only operated in the winters and had a $25 extra fare. However, as the booklet notes, “The Chief is far more magnificent; it leaves daily, instead of weekly, and it costs less than half the old extra charge,” namely a $10 extra fare (about $130 in today’s money).

Like the de Luxe and unlike most limited trains of that era, the Chief was mostly rooms rather than sections. With 15 drawing rooms (three beds each), 11 compartments (2 beds each), and 20 sections (2 beds each), more than 60 percent of the train’s 107 beds were in rooms, not open sections. Of course, not all beds were likely to be occupied in the rooms, but many sections were also likely to have only their lower berths occupied since people had the option of buying both berths so they would have more headroom at night and room to spread out during the day.

The booklet even repeats Santa Fe’s slogan for the de Luxe: “Extra fast, extra fine, extra fare.” The Chief took 63 hours to get from Chicago to Los Angeles, five fewer than the California Limited. The same day that Santa Fe began running the Chief, Union Pacific and Southern Pacific speeded up the Los Angeles Limited and Golden State Limited to a 63-hour schedule and both also began charging extra fares. These trains continued to have more beds in sections than in rooms but otherwise matched most of the Chief‘s amenities.

This booklet comes with five illustrations showing the interior of the train and floor plans of each of the six cars on the train. The illustration of the club car shows a smoking room with a dozen wicker seats and a “reading room” with seats facing each other like a section. There’s even an overhead bed waiting to be folded down. These beds may have been used by the train crew at night.

“A far, strange land is California,” advises the booklet. “Its cities are like treasure palaces of Bagdad, filled with exotic jewels, carved jade and crystal, tortoise shell, hand- wrought silver and painted fans. There are ravishing fabrics from lands afar, and delicate trifles perfumed with sandalwood, ylang-ylang, and jasmine flower. There are bazaars and streets of bazaars, with temple roofs and tingling bells, the boom of solemn gongs, and the wafting of incense.” California is still pretty strange today, but I don’t know if any part of it ever looked like Bagdad.

In addition to the Chief, travelers to California had their choice of four other Santa Fe trains: the all-Pullman California Limited, which took 68 hours to get from Chicago to Los Angeles (compared with the Chief‘s 63 hours); the Navajo, which also took 68 hours; the Scout, which took 74-1/4 hours; and the Missionary, which took almost 69 hours.

Of these trains, the Chief was easily the best. “You will agree with us that this train is well worth” the extra fare, says the booklet.

“No other transcontinental line operates five trains every day to California, under one management for the entire distance,” assures the booklet. In fact, Union Pacific had six trains — five limiteds and a mail train — from Chicago to California, but they weren’t under one management for the entire distance, not that passengers would have been acutely aware of that.