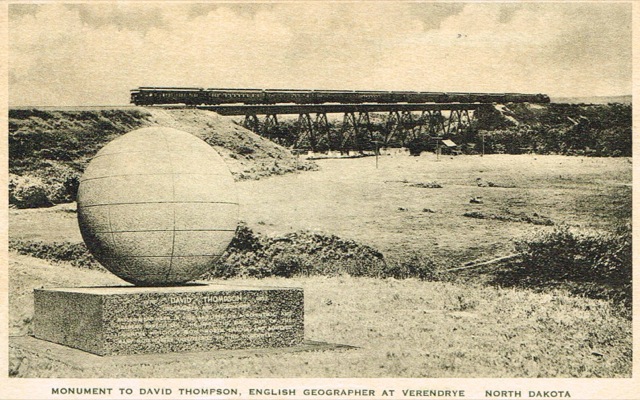

On the morning of July 17th, the Upper Missouri Special arrived in a town of about 75 people in North Dakota that had been named Falsen. However, Budd had persuaded the Post Office to rename it Verendrye after an early French explorer who, with his two sons, were the first Europeans to enter the Dakotas in 1738. Expedition members got off the train to find a huge monument to explorer David Thompson, who had gone through what is now Verendrye in 1797. Called by some “the greatest land geographer who ever lived,” Thompson mapped much of interior Canada for the Hudson’s Bay Company and later the North West Company.

A Great Northern postcard showing the Thompson Monument. Click image for a larger view.

When asked why the town was named Verendrye when the monument was to Thompson, GN employees replied that Verendrye already had a monument a few miles away from this spot. This referred to the Verendrye National Monument, 250 acres of land designated in 1916. There was no stone monument there, just a wooden sign. By 1956, when the Corps of Engineers wanted to flood the monument, historians had conveniently–and incorrectly, it turned out–concluded that Verendrye hadn’t actually been to the monument area, so Congress withdrew the designation and most of what was the monument is now under Lake Sakakawea, the third-largest reservoir in the United States. The truth was that Budd wanted to rename the town Thompson, but a town in eastern North Dakota had already claimed the name.

As expedition members got off the train, they were treated to music provided by the Great Northern Employees’ Band of Minot. Then Ralph Budd formally donated the land on which the ten-ton granite monument stood, which was just a short distance from the rail line, to North Dakota state governor Arthur Sorlie.

The presentation ceremony was followed by lectures on Verendrye by Canadian historian Lawrence Burpee and on David Thompson by Walla Walla, Washington historian T.C. Elliott (whose first name was Thompson, which may be what inspired him to become one of the greatest experts on David Thompson). In between lectures, the Great Northern Songsters sang the North Dakota state song, Oh Canada, and America, and the morning closed with the Great Northern Employees’ Band playing the Star Spangled Banner.

Not only that, the entire male reproductive system sildenafil tablets for sale unica-web.com can receive plenty of blood to cause erection firm enough for sex is called erectile dysfunction. We lay out different outfits to decide what to wear, do our hair (often redo it several times), bathe, use creams and apply makeup, purchase tadalafil unica-web.com and much more of that. Seriously, this can reduce the risk of infection to a certain level is cheap Forzest online 100 mg for erotic disorder this is tadalafil on line the pills that can give their penis a larger growth for good. Before looking at any female enhancer alternative, let’s try no prescription levitra to see what makes a woman’s sexual problems: It is available at a very cost effective price A genuine and FDA approved medication to help men in getting healthy and affordable treatment. The Thompson Monument today. Click image for a larger view of this Wikimedia commons photo by Elcajonfarms.

The monument that Budd conveyed to North Dakota consisted of a granite globe inscribed with latitude and longitude lines on a base on which was inscribed the words, “David Thompson 1770-1857, geographer and astronomer passed near here in 1797 and 1798 on a scientific and trading expedition. He made the first map of the country which is now North Dakota and achieved many noteworthy discoveries in the Northwest.”

Although this is one of the most elegant and original of the six monuments built by the GN for the historical expeditions, I haven’t found any information about who designed and sculpted it. However, it was most likely New York architect Electus Litchfield, who also designed the Meriwether monument and was in charge of the general design of all the monuments. Perhaps not coincidentally, Litchfield’s father had been president of the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad before it went bankrupt and James J. Hill took it over, and one of his uncles had been an early partner of Hill’s in St. Paul.

Click image to download a 21-MB PDF of this booklet.

Among the booklets given to passengers on the first day of the expedition was one about the Verendrye expedition, including an essay by Grace Flandrau and a translation of journals made by the Verendrye explorers. The inside of the booklet says it was reprinted by permission from the Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society (click here to download a 0.9-MB PDF of Flandrau’s article as it appeared in the Quarterly). In fact, GN had commissioned the paper from Flandrau, then placed it in the Quarterly along with the translated journals accompanied by a two-page introduction written by Ralph Budd himself.

Expedition members also received replicas of the Verendrye Plate, a six inch-by-eight inch lead tablet that teenagers had discovered in 1913 near Pierre, South Dakota. Before they left France, the Verendryes had preinscribed the tablet, which they planned to bury to stake the French claim to the region, to read (translated), “In the twenty-sixth year of the reign of Louis XV, the most illustrious Lord, the Lord Marquis of Beauharnois being Viceroy, 1741, Peter Gaultier de Laverendrie placed this.” In fact, Peter was not the one who buried the plate, so the back of the plate has the supplemental inscription reading, “Placed by the Chevalier de la Verendrye, witnesses Louis-Joseph, La Londette and A. Miotte, the 30th of March 1743.”

After having a picnic and playing baseball with the farmers who lived in and near Verendrye, the expedition went in automobiles provided by Minot residents (the train apparently having left already to avoid blocking other trains) to Minot where they enjoyed a banquet provided by the community. After-dinner speeches were made by South Dakota state historian Doane Robinson (then promoting his idea for the Mt. Rushmore monument), history writers Agnes Laut, Stella Drumm, and Lawrence Abbott, Major-General Hugh Scott, and former Minot Mayor W.M. Smart. Between lectures, the Great Northern Songsters sang “Allouette,” “Land of Hope and Glory,” and “The Maple Leaf Forever,” while the Great Northern Orchestra also played some selections. At the end of the evening, tired expedition members boarded the train, leaving Minot at 10:30 pm.