Eight of the papers that the Great Northern commissioned for the Upper Missouri and Columbia River Historical Expeditions were written by St. Paul native Grace Flandrau. Handpicked by Louis Hill and Ralph Budd, Flandrau was a strange choice, as she was a fiction writer who had never before published non-fiction much less historical research.

Grace Flandrau seven years before the Great Northern hired her to write several historical essays.

Born Grace Hodgson in 1886, she grew up in a family in which, “although there was generally not enough money for the barest necessities, there was always enough for the luxuries.” Her father did well in real estate and banking until the Panic of 1893, after which he barely avoided bankruptcy. As a result, says her biographer Georgia Ray, she was “conditioned to a life of luxury while living in dread of poverty,” which led her to develop the cynicism many people feel about the classes they envy.

In 1909 she married Blair Flandrau, an apparently wealthy playboy whose actual finances were none too secure; though in love, both parties to the marriage apparently thought they were marrying into wealth. As Blair tried to run a coffee plantation in Mexico in the face of the Mexican Revolution and his own ignorance about farming, she supplemented their incomes with writing, selling her first fiction to Sunset magazine in 1912. By 1923, she had written three novels, one of which would be made into a silent movie in 1924. Popular magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post, Scribners, and H.L. Mencken’s The Smart Set paid her as much as $350 for her short stories–close to $5,000 today and nearly six-months pay for a typical working-class employee.

Like her brother-in-law Charles Flandrau, Grace was sometimes compared with fellow Minnesota native F. Scott Fitzgerald. All three wrote satires about high society; in Grace Fladrau’s case, specifically about St. Paul high society. She remained more-or-less an outsider looking in, which made her stories popular among the middle-class but which alienated members of St. Paul’s high society. At the time, of course, few women had careers other than homemaking, child-raising, and acting as hostesses for their husband’s socializing, so Grace’s success was unusual.

Writers always fear that their success is ephemeral. In March, 1923, she wrote a friend, “What if I’ve shot my wad? It makes me damned scared to see what they [her publishers] expect of me. What if I can’t do it?”

Fortunately, soon after writing that letter she was approached by Louis Hill and Ralph Budd asking her to write for the Great Northern Railway. Perhaps her connections with high society brought her to Hill’s attention, or perhaps her literary skills caught Budd’s attention. In any case, they proposed a two-year project during which she would have a pass to ride the Oriental Limited and other trains to sites and collections of historical interest and free use of the caretaker’s cabin on Hill’s ranch next to Glacier National Park.

“They’re hiring me to put a few fancy literary frills [on pamphlets] they’re going to get out,” she wrote a friend. “I think it will be a great lark to try. Also to work with the delectable and so fabulously intelligent Mr. Budd.”

Not surprisingly, her work led to rumors that she and Budd were having an affair. Budd was seven years older than Grace, but her husband was eleven years older. However, a friend of hers said that “it would have been out of character” for her, and probably for Budd, the Iowa farmboy, as well. An affair might have been in character for Hill; fourteen years older than Flandrau, Louis drank heavily and was estranged from his wife for many years. But it seems unlikely.

Ray says Flandrau wrote eleven essays for the Great Northern, but only lists ten. The first was The Oriental and Captain Palmer, a 1924 pamphlet about Nathaniel Palmer, an early designer of nineteenth-century clipper ships and pioneer in shipping between Asia and North America. This was given to Great Northern employees, agents, and passengers who happened to ride its trains on Christmas day, 1924.

Second, in all probability, was Seven Sunsets, which was more of an advertising brochure for the Oriental Limited than a history essay. This probably dates from 1924 or early 1925, soon after the train was completely re-equipped.

The other eight were distributed during the historical expeditions, including:

- The Verendrye Overland Quest of the Pacific

- A Glance at the Lewis & Clark Expedition (in a later edition called simply The Lewis & Clark Expedition with different pictures and several pages of additional text);

- The Story of Marias Pass (in an otherwise identical edition called The Discovery of Marias Pass)

- Historic Northwest Adventureland (in a later edition called Historic Adventureland of the Northwest, with different pictures but identical text)

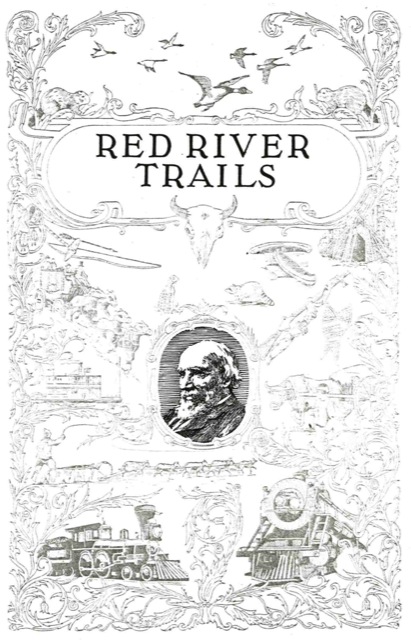

- Red River Trails

- Frontier Days Along the Upper Missouri

- Koo-koo-sint, the Star Man: A Chronicle of David Thompson

- Astor and the Oregon Country

The first three were distributed during the Upper Missouri Expedition and were posted here over the last few days. The last five were distributed during the Columbia River Expedition and will be posted here over the next few days.

The Christmas edition of Red River Trails pictured James J. Hill, the William Crooks, and the Great Northern’s latest 4-8-2 passenger locomotive on the cover. Ciick image to download a 5.7-MB PDF of this booklet. The edition distributed during and after the Columbia River Expedition will be posted here in a few days.

A version of Red River Trails was also given out for Christmas, 1925, just as The Oriental and Captain Palmer had been given out for Christmas, 1924. The text of the two versions are identical, but the graphics are not. Both included maps comparing the Red River trails with the routes of the Great Northern, but the Christmas map also shows the interesting coincidence that Verendrye, Thompson, and Lewis & Clark all spent different Christmases in North Dakota within a few miles of one another, though separated by decades. The Christmas version is signed by Ralph Budd and seven other GN executives, but Flandrau’s authorship is indicated only by a “G.F.” at the end of the essay.

Despite having an idyllic workplace near Glacier Park, Flandrau’s quest for perfection (and her desire to please Budd) made the job difficult. “The project involved condensing three hundred years of Northwest history–with all the people and circumstances impacting its destiny–into several pamphlets of stirring prose,” says Ray. Though the largely self-educated Flandrau never went to college (her main education was in a French boarding school, which probably did little good to aspiring writers in English), yet “the task would have challenged any doctoral candidate to the maximum.”

The stress was finally too much and she ended up spending six weeks being treated for “nervous exhaustion” in a Spokane hospital in early 1925. This could explain why Red River Trails, Frontier Days, and Koo-koo-sint were not published until the Columbia River Expedition even though they were just as appropriate for the Upper Missouri.

Still, Flandrau’s meticulous research was good enough that the Oregon Historical Society published her Verendrye paper in its quarterly journal. The opportunity to do that research proved a turning point in her career. Her next book, Then I Saw the Congo, a travelogue of a six-month trip she and her husband took through Africa in 1927, won praise from critics and was a best seller. She continued to write short stories for magazines but also wrote many non-fiction pieces, such as biographical articles for Golfer and Sportsman.

Published in 1934, her last novel was semi-autobiographical and did poorly, possibly because of the hostility she had generated among the upper crusts from her previous books or possibly because the Depression had rendered that sort of writing out of style. Her brother-in-law, Charles, died in early 1938, leaving $250,000 to Blair, who died later that same year giving her a combined estate of more than $300,000, leaving her (as Ray puts it) “wealthy but lonely.” She wrote little after that, though it is impossible to say whether that was because she was discouraged by the failure of her last novel (as Ray suggests) or because for the first time in her life she was so financially secure that she no longer needed to earn an income. She spent most of the rest of her years in Connecticut and Arizona.

She stayed in touch with Budd, about whom she wrote in 1939, “I think I like him best still of any living person.” Budd (who by this time was living in Chicago) tried to interest her in writing more railroad pamphlets, but other the editing some of his speeches and other writings, she generally declined.

By the time she died in 1971, she had somehow combined the $307,000 she inherited from her husband and her royalties from writing into an estate worth more than $8 million. She left $1.5 million to various Minnesota charities, including the Minnesota Historical Society. She also gave $800,000 to the University of Arizona in Tucson, which the school used to build the Grace Flandrau Planetarium. For some reason, she gave one of her largest gifts, $3 million, to the National Council on Crime and Delinquency on the condition that they move their headquarters from New Jersey to Tucson. They did, but stayed for less than five years; they are now headquartered in Oakland.

Curiously, an article by Georgia Ray about Flandrau published by the Minnesota Historical Society says nothing at all about her life in Arizona, while an article in the Arizona Daily Star seems to regard her early years in Minnesota as a mystery, even getting her birthdate wrong by ten years. This is especially puzzling as Ray’s biography, Voice Interrupted, was published two years before the Daily Star article. That biography does mention Tucson, but not in any great detail.

Flandrau’s work for the Great Northern occupied only two of her 85 years. But the papers she wrote for the railway may be her longest-lasting legacy, partly because they were widely distributed by the railroad and partly because the subject matter, unlike most of her fiction, remains of interest to this day.