The schedules and even the advertising in this timetable are almost unchanged from the 1950 timetable presented here yesterday. The biggest difference is that the timetable now lists Missouri Pacific as the California Zephyr‘s connection to St. Louis, instead of Union Pacific-Wabash as in previous timetables. The Missouri Pacific connection was in Omaha instead of Denver, which meant eastbound passengers had to get off the Zephyr at 4:55 am instead of 7:00 pm for the UP connection, and then wait three hours for the MP train instead of an hour for the Denver connection.

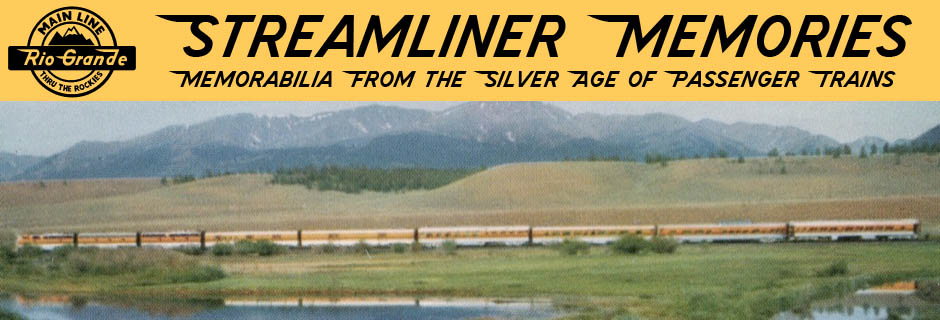

Click image to download a 4.7-MB PDF of this 8-page timetable.

Click image to download a 4.7-MB PDF of this 8-page timetable.

With negligible other changes in the timetable, this is a good time to discuss one of the technologies that made twentieth century railroading possible. I’ve discussed such technologies before, including Diesels, metallurgy, air conditioning, and paint. Today’s technology is more prosaic.

As we have seen, for much of the nineteenth century, railroad timetables consisted of a 4″x9″ brochure that unfolded to a sheet as large as 24″x40″. One side had the schedules and sometimes some advertising and the other had a large map of the area served by the railroad. These timetables were unwieldy when unfolded and often developed holes at the corners of the folds.

These problems were solved with a new technology known as the staple. Staples were invented in the 1870s but — according to a web site on the history of timetables — were not adopted to commercial printing until 1889.

Over the next decade after that, railroads switched from the brochure format to the 8″x9″ stapled format most common in the twentieth century. In 1893, for example, Burlington issued a brochure-style timetable that is in the David Rumsey Collection while in 1894 it published a stapled timetable that is posted on WX4.

The web site on the history of timetables laments that maps in the stapled timetables were necessarily smaller than on the brochure-style timetables, with the centerfold page typically measuring around 16″ wide by 9″ high. Railroads could add more pages of maps, but I suspect that other improvements in printing technology, such as the replacement of wooden blocks with metal plates, helped offset the problem of smaller maps.

It seems appropriate to bring up the technological innovation of staples with this timetable because it is a multi-page timetable that doesn’t use staples. Though it is eight pages long and thus requires two 16″x9″ sheets connected together, it isn’t stapled. Instead, the sheets are glued together. Apparently, glue was cheaper than staples if only two sheets were to be connected.

Glue has the disadvantage, however, that is is more two dimensional than staples. Stapled timetables could open to lay flat on every spread. A glued timetable opened to lay flat only on the centerfold spread. Other spreads were restricted from laying flat by the width of the glue strip. This may be more of a problem for someone like me, who is trying to scan the pages, than to passengers, but in some cases the passengers might be annoyed to find that the edges of the printed schedules were obscured by the glued pages.