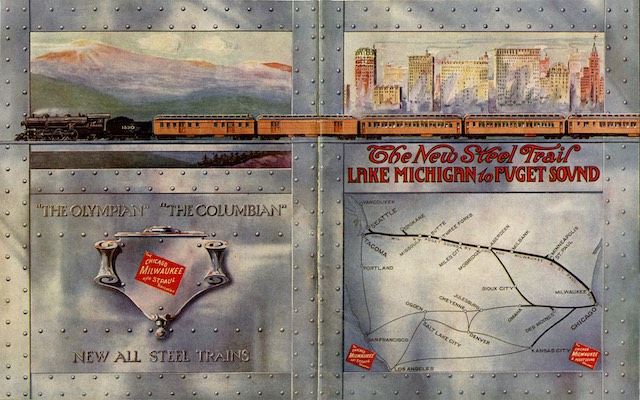

The brilliant cover of this booklet was designed to remind travelers that only the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul offered all-steel trains between Chicago and the Pacific Northwest in 1911. At that time, the steel industry, though more than 50 years old, was a hot commodity. The ten-year-old U.S. Steel Corporation was the largest company in the world and controlled two-thirds of the American steel market, leading to the same debates over monopolies that we hear today about Google and other high-tech companies.

Click image to download a 10.6-MB PDF of this 36-page booklet. Click here to download a PDF of the front and back cover as shown above.

Click image to download a 10.6-MB PDF of this 36-page booklet. Click here to download a PDF of the front and back cover as shown above.

Steel, an alloy of iron and carbon, wasn’t as fast moving as the high-tech industry is today, but it was still transforming America in the early twentieth century. The first large-scale steelmaking, using the Bessemer process, could be traced back to the 1850s. The first railroad to experiment with steel rails was in England in 1857. Yet as late as 1880, more than 70 percent of American rails were still made of iron. By 1900, however, more than 90 percent were steel.

The steel trail of this booklet, however, refers not to rails but to passenger cars. As previously described here, all passenger train cars were wood until the 1900s, when the Pennsylvania Railroad began building and ordering cars made of steel.

When the St. Paul road (or, as this booklet calls it, the “St. Paul-Puget Sound system”) built its Pacific Extension, it knew it needed a way to distinguish itself from its entrenched rivals, so it became the first railroad in the West to have an all-steel train. This is emphasized by the faux-shiny surface of the booklet cover, a theme repeated throughout the booklet’s interior. Of course, the steel of the cars wasn’t actually visible as it was painted to protect it from rust.

In fact, the railroad had two steel trains running to the Northwest: the Olympian and the Columbian. The booklet notes that the two were identically equipped except that the Columbian didn’t have a lounge-observation car. They left Chicago about 12 hours apart, the Olympian departing at 10:15 pm and the Columbian at 10:00 am. But the Olympian made fewer stops, so was a little faster, arriving in Seattle at 8:00 pm (71-3/4 hours or 30.4 mph) while the Columbian arrived at 11:10 am (75-1/6 hours or 29.0 mph).

In anticipation of the St. Paul’s opening, the Great Northern and Northern Pacific each arranged for one of their trains, the Oriental Limited and Northern Pacific Express, to go through to Chicago over the Burlington. But, initially, only the St. Paul had two Chicago-Seattle trains. It would be more than a decade before GN and NP offered all-steel trains and while the NP did, for a few years, have two Chicago-Seattle trains, the GN rarely if ever ran its secondary train all the way to Chicago.

Update: After the Great Northern introduced the Empire Builder in 1929, the secondary Oriental Limited operated as its own train to Chicago until it was discontinued due to the Depression. After it was re-inaugurated in 1947, coaches, sleeping cars, and lounge cars for it and its successor, the Western Star, operated through to Chicago as part of the Burlington’s Blackhawk.

This booklet isn’t dated, but the list of agents in the back matches that of the 1911 Official Railway Guide. This was scanned by Google and can downloaded for free.

The Western Star appeared to be a Chicago – Seattle train, but in reality it was two services, with an exchange of through cars between Chicago and the Twin Cities. The same probably applied to the Mainstreeter.