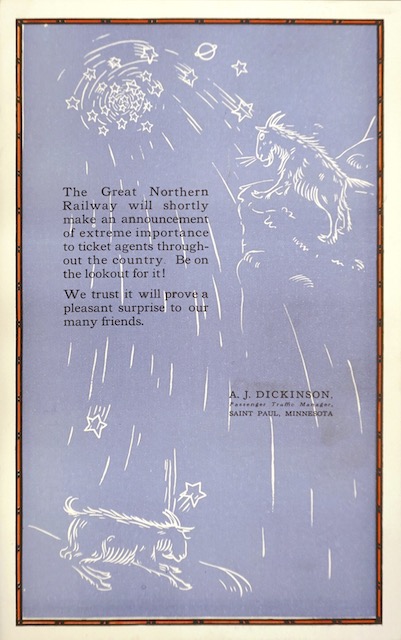

“The Great Northern will shortly make an announcement of extreme importance to ticket agents throughout the country,” says this card, which was mailed out to agents in late 1923 or early 1924. “Be on the lookout for it!”

Click image to download a 1.6-MB PDF of this flyer.

Click image to download a 1.6-MB PDF of this flyer.

Since I found this at the Minnesota History Center when I was looking at documents from around 1924, I’m pretty sure the planned announcement was for the debut of the New Oriental Limited, which began running that year. Other announcements may have been possible, but they weren’t likely to be of extreme importance to ticket agents.

The other side of the card has space for a stamp and address but also has a drawing of a mountain goat tapping on a telegraph key. At the top are five lines of Morse code, which I translate to read:

The Great Northern

Railway will soon

broadcast news of

great importance to

you hold the air please

In radio circles, “hold the air” is normally a request for silence in order to make the air waves available for messages of crucial importance. In this context, I suspect it means stand by for the forthcoming message, though I’m surprised that telegraphers would refer to their communication systems as “air.”

Having made this translation, I am also surprised at the complexity of Morse code. I always thought it was just dots and dashes, but it turns out the gaps between the dots and dashes are important too.

Two dots close together are an I, while two dots with a slight gap between them are an O and two dots with a bigger gap can mean EE. Three dots close together are S while a slight gap between the first and second of three dots make them an R and a slight gap between the second and third represents a C. Four dots are an H but if there is a small gap between the second and third they form a Y and gaps between the other dots also represent other letters.

Due to this complexity and the ambiguity of how they are printed on the card, I was able to translate some of the letters in the message only within the context of adjacent letters. For example, the dash and dots representing “to” in the fourth line are close enough together that it looks like a D and together they are close enough to the previous dots that it looks like a letter and not a separate word. But “importanced” is not a word so in context it only makes sense if the D (dash-dot-dot) is really “to” (dash dot-dot). Thanks to Chris Hausler for figuring this out.