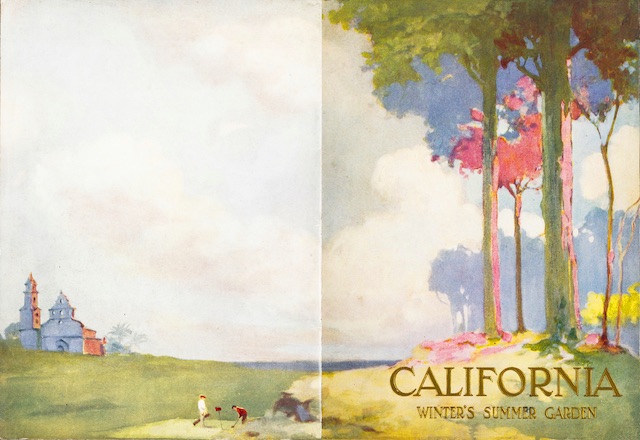

This booklet is posted on archive.org, but the illustrations in that digitized version are so faded they are hardly visible. I’ve done my best to bring them out to what I hope is close to their original appearance.

Click image to download a 8.8-MB PDF of this 20-page booklet.

Click image to download a 8.8-MB PDF of this 20-page booklet.

“There is but one California,” says the booklet, “and when you consider excellence of service, elegance of equipment and comfort of travel, there is but one way to travel — via The San Francisco Overland Limited of the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul-Union Pacific-Southern Pacific Line.”

In truth, if there was only one way to travel to California, it was via the Overland Limited of the Chicago & North Western, not the St. Paul road. Both trains left Chicago at the same time, and while the North Western train arrived back in Chicago five minutes before the St. Paul train, the real difference was in the equipment. The North Western train, including diner and observation cars, went all the way through to Oakland, while the St. Paul train went only to Omaha where one or two sleeping cars were transferred to the Union Pacific train of the same name. Moreover, the St. Paul train carried coaches, demeaning its exclusivity, while the North Western-Union Pacific train didn’t even carry tourist sleepers, much less coaches.

Adding to the confusion, the St. Paul road numbered its Overland Limited trains 1 & 2, the same as the North Western. What was confusing was that the St. Paul had another westbound train, the Pioneer Limited, that was also numbered 1. Though its eastbound counterpart was #4, another Minneapolis-Chicago train was #2. But the confusion would have been among westbound passengers boarding number 1 for Minneapolis thinking they were going to San Francisco or vice versa.

I’m not sure when, but not too many years after this booklet was published in 1913, the St. Paul road gave up the sham that it was running the Overland Limited when all it was really doing was trying to confuse the public by capitalizing on a name popularized by another railroad.

The St. Paul wasn’t the only railroad to do this; at various times Burlington had a train called the Overland Express that connected at Denver with Rio Grande/Western Pacific trains to the West Coast and until 1915 Santa Fe had a train called the Overland Limited, or sometimes the Overland Express, that went from Chicago to Los Angeles. But neither of these railroads were brazen enough to compete with C&NW for passengers connecting to the UP train to the Bay Area.

Aside from this, the book is beautiful, with most of the pages filled with watercolor paintings with inset black-and-white photos that are tinted with an orange-brown color. Unfortunately, the book doesn’t identify the subjects of any of the photos, and while some are recognizable, a few are not. One of the photos shows San Francisco’s flatiron-shaped Crocker Building.

The watercolors are similarly unlabeled. While one appears to depict redwoods and another Catalina Island, some appear to be imaginary scenes. The one on the same page as the photo of the Crocker Building shows a downtown San Francisco scene dominated by the Mutual Savings Bank Building, a 1902 building that survived the earthquake. Unfortunately, neither the covers nor the interior paintings are signed.