The New York Central had eight trains a day between New York and Chicago, four between New York and St. Louis, and plenty of additional trains connecting Buffalo, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, and Pittsburgh with each other and with New York and Chicago. Today, these are considered Rust Belt cities, but in the 1950s, they were the industrial heart of America and New York Central was the main connection between them.

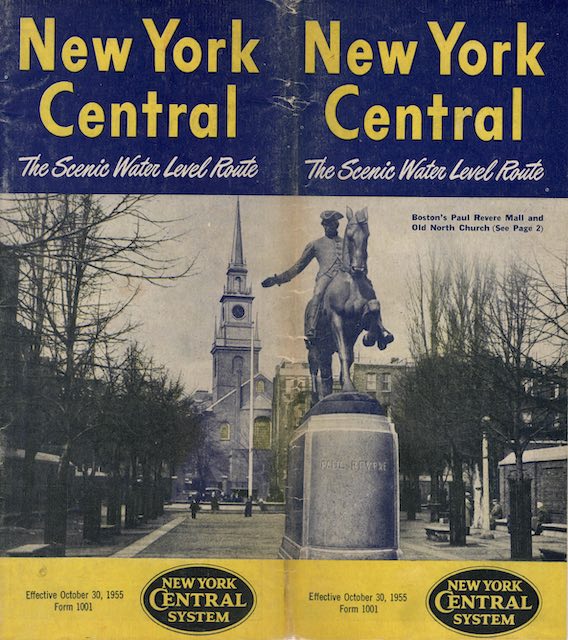

Click image to download a 29.7-MB PDF of this timetable contributed by Ellery Goode.

Click image to download a 29.7-MB PDF of this timetable contributed by Ellery Goode.

While the 20th Century Limited cleaned the clock of the Broadway Limited, the Pennsylvania earned more income and was more profitable than the Central during most years of their lives. Both railroads had a little more than 10,000 miles of track, but in the early 1950s, the PRR was making revenues of more than a billion dollars a year, while the NYC was around $800 million, and PRR profits were around $35 million to $40 million per year compared with NYC profits of $15 million to $25 million per year.

The above timetable image is the back cover, while the front cover is a now highly inappropriate advertisement for the Central’s “husband-wife plan,” which allowed businessmen to take their wives on business trips, getting round-trip fare for the cost of a one-way ticket. “When you arrive, your ‘better half’ becomes the perfect hostess. She can make your business entertaining easy and gracious, whether at cocktails, dinner or the theatre,” says the ad. “And while you’re tied up in meetings, she can have a wonderful time — sight-seeing, visiting old friends, or shopping for a new wardrobe.”

The inside front cover described the through coast-to-coast sleeping cars. These included the 20th Century Limited and Super Chief, the Commodore Vanderbilt and City of San Francisco, the Wolverine and City of Los Angeles westbound but City of Los Angeles and Commodore Vanderbilt eastbound, and finally the Commodore Vanderbilt and California Zephyr. The City of Los Angeles was daily while the Commodore/Zephyr and Commodore/City of San Francisco combinations were every other day (alternating with each other and with the Pennsy) and the Century/Super Chief was, for some reason, replaced by the Commodore/Super Chief on Saturdays and certain holidays.

All of this made the Commodore Vanderbilt a pretty important train. The Central’s equivalent of PRR’s General, the all-Pullman Commodore left New York 30 minutes before the Century and arrived in Chicago 15 minutes before, thus taking only 15 minutes longer.

As I’ve noted before, the problem with all of these through sleeping cars was that the Central’s (and Pennsy’s) premiere trains all arrived in Chicago in the mornings and the western railroads’ premiere trains all left in the evenings and vice versa. Thus, passengers were stuck in Chicago for up to ten hours and didn’t save any time by taking a through car.

It’s hard to say, but if the railroads had managed to tighten this up, allowing for coast-to-coast trips in under 2-1/2 days, the through sleeping cars might have lasted beyond 1958. To do that, they would have had to overcome not just management inertia but the problem of shuttling cars between Chicago’s many stations.

The timetable also advertised daily connections at St. Louis between New York Central trains and Texas-bound trains via the Frisco and Missouri Pacific railroads. This was slightly deceptive, however, as the Central didn’t offer through cars to Texas, while the Pennsylvania had sleeping cars from New York to El Paso, Houston, and San Antonio as well as Washington to Houston.

Some coordination between the western and eastern railroads might have been helpful too.

A morning arrival in Chicago would not be problematic, if the connections were the Chief (leaving at 9) or the Golden State, which had an early afternoon departure. For the San Francisco trains, either PRR or NYC had late evening NY departures, which arrived in Chicago mid-afternoon IIRC.