In 1905, the Pennsylvania Railroad used 4-4-2 Atlantic-type locomotives to power the 18-hour Pennsylvania Special. With 80″ driving wheels and about 21,000 pounds of tractive effort, these locomotives weren’t as powerful as the newer 4-6-2 locomotives, but the Special didn’t need that much power because it was typically a four- or five-car train.

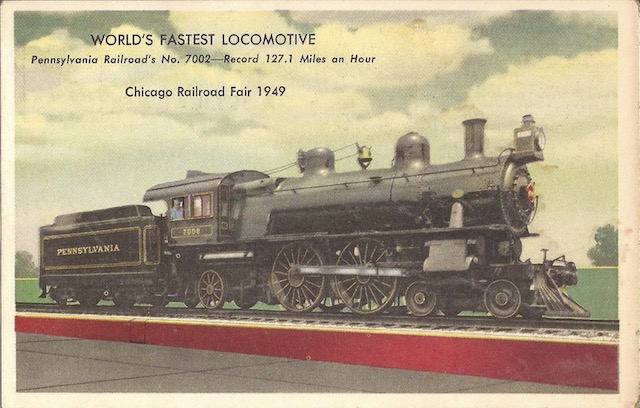

Pennsylvania scrapped locomotive 7002 in 1935, so it repainted locomotive 8063 to look like it and put it on display at the 1949 Chicago Railroad Fair. Click image to download an 885-KB PDF of this postcard.

On its first day as an 18-hour train, the westbound Special was being pulled by 4-4-2 locomotive no. 7002. The train was late to Crestline, Ohio, and the engineer was told to do whatever he could to make up time. In the three miles between Lima and Elida, Ohio, he supposedly drove the train at an average speed of 127.1 miles per hour, turning a potential public relations disaster into a public relations boon.

In fact, this speed is even more questionable than the 112-mph speed record supposedly set by the New York Central’s 999 in 1893. The 127-mph rate was based on times recorded by tower and station operators in Lima and Elida, and there is no guarantee that their watches were synchronized. Though the railroad required them to set their watches to a telegraph signal once a day, they only had to be accurate to the nearest minute. While the 7002 had a bigger boiler than the 999, William Withuhn (in American Steam Locomotives) estimates that it was not big enough to support speeds above 110 mph.

Recognizing the benefit of more evocative names, PRR changed the name of the Pennsylvania Special to Broadway Limited in 1912. In 1914, to meet demand for longer trains, Pennsylvania developed a 4-6-2 Pacific-type locomotive known as a K4. Like the Atlantics, it had 80″ drivers but developed more than twice the tractive effort of the 4-4-2s. The railroad liked it so well that it built 350 of them and ordered 75 more from Baldwin, making it the largest run of any single class of passenger steam locomotives in the U.S. Although the Pennsylvania route between New York and Chicago had to deal with much steeper grades than the New York Central’s water-level route, the railroad continued to use these and similar 4-6-2 locomotives for its passenger trains for some two decades after the Central had introduced the Hudson locomotive type.

This painting by Harold Brett shows the Broadway Limited being pulled by a 4-6-2 locomotive. The Broadway was not named after the street but after the railroad’s broad, four-train main line, and as this card indicates the railroad was a little uncertain about whether it should be called “Broadway” or “Broad Way.” This postcard is undated but I’ve seen ones like it postmarked as early as 1923. Click image to download a 1.9-MB PDF of this postcard.

The Pennsylvania never would own any Hudsons or Northerns, two locomotives that are often identified as the ultimate in passenger power before Diesels. Instead, it experimented with “duplex locomotives,” which typically had eight drivers but four pistons so that each pair of pistons powered only four drivers. Unlike an articulated locomotive, the two sets of drivers did not swivel independently of one another, but the four pistons allowed for better balance at high speeds.

In 1936, when it was still using Pacific locomotives for most of its passenger trains, it designed a 6-4-4-6 locomotive that was capable of going 100 mph. It reportedly experienced too much wheel slip, so only one was made. Then, in 1944, it built a non-duplex 6-8-6 locomotive — effectively a Northern but with six-wheel leading and trailing trucks — that was powered by a steam turbine instead of the more usual pistons. Again, only one was made.

Streamlined by Raymond Loewy, Pennsylvania’s T1 duplex locomotive pulling the Broadway Limited appears to be racing Henry Dreyfuss’ Hudson pulling the 20th Century Limited in this painting by Russ Porter. Click image for a larger view.

Finally, in 1945, it built another duplex 4-4-4-4 locomotive. These locomotives, one of which is shown in the illustration above, still suffered from wheel slip, but the railroad nevertheless built more than 50 of them to handle its passenger trains. It is likely that these locomotives would never have been built if World War II restrictions had not limited the number of Diesel locomotives built in the early 1940s. They were all scrapped by 1956, but despite their slipperiness someone is trying to build a full-sized replica.

Despite their competition, the New York Central and Pennsylvania had a quiet or unspoken agreement to run only one limited train each on an 18- to 20-hour schedule between New York and Chicago. Yet in the 1920s, the railroads had so sold the public on 20-hour trains that they were having to run each train in multiple sections. The 20th Century routinely ran as two and three sections and at least once in seven sections.

An appendix in Lucius Beebe’s book on the 20th Century Limited includes a lengthy 1926 memo (1.7-MB PDF) by PRR traffic inspector John Barriger — who would later become a railroad executive noted for his ability to rescue weak companies from bankruptcy — arguing that the policy of just one 20-hour train per day was working to the detriment of the Pennsylvania Railroad, partly due to the New York Central’s better marketing. Barriger also noted that the Broadway and Century arrive too early in and departed too late from Chicago to make good connections with West Coast trains.

He urged the railroad to run more 20-hour trains at different times of the day, including ones that would more closely connect with trains to the West. The railroad took his advice in 1929, speeding up the Pennsylvania Limited, Manhattan Limited, and Golden Arrow to 20-hour schedules. Some of these trains made much better connections with western trains than the Broadway had done.

The New York Central, of course, immediately responded by introducing the Advance 20th Century Limited and Commodore Vanderbilt on 20-hour schedules and reducing the time of the Wolverine (which went via Detroit) to 20 hours. The eastbound Fast Mail (which carried coaches and sleepers) was also reduced to 20 hours, and other trains were reduced to 20 hours and 50 minutes.

Counting the Fast Mail, the Central had one more 20-hour train than the Pennsylvania, but most of the former’s trains were timed to take the pressure off of the 20th Century, while the Pennsylvania did a slightly better job of connecting with western trains. I don’t have any record of whether Barriger’s advice helped PRR capture more of the New York-Chicago market, but it definitely benefitted travelers.