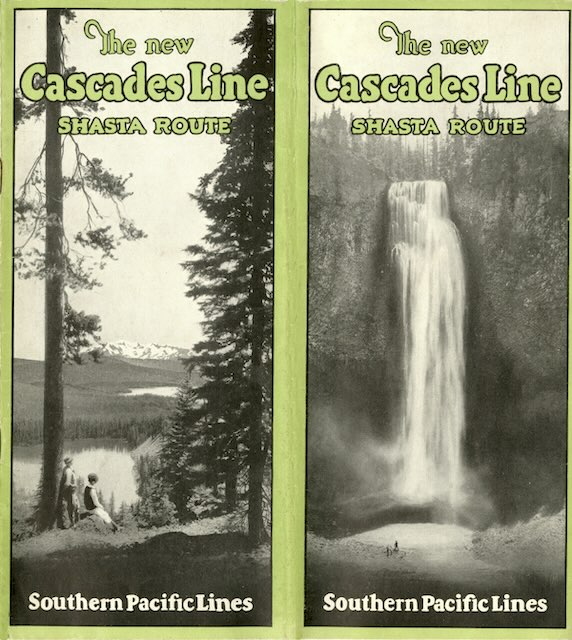

This booklet announces the February 1926 completion of 277 miles of new railroad between Springfield Oregon and Black Butte (near Mount Shasta) California. More than two decades in the making, the new line eliminated many sharp curves and grades on the Siskiyou Mountain route that had been completed in 1887. Even though the new line had to climb over the Cascade Mountains, it soon became Southern Pacific’s main north-south line in Oregon.

Click image to download a 6.5-MB PDF of this 16-page booklet.

Click image to download a 6.5-MB PDF of this 16-page booklet.

The story began in 1866 when Congress passed the Oregon & California Railroad Land Grant Act promising 3.7 million acres of land to anyone building a railroad from Portland to San Francisco. Two companies competed to get the grant, one building down the east side of the Willamette Valley and the other further west. The east side line made it a little beyond Springfield while the west side line went to Eugene and reached the California border in 1887. Also in 1887, both lines came under the control of the Southern Pacific, which in 1901 was taken over by Edward Harriman.

Even in the 1870s, when the lines were being built, it was clear to rail surveyors that a route over the Cascades would be superior to the Siskiyou line that was built. While Cascade Mountain passes were nearly a thousand feet higher than the Siskiyou Summit, the Siskiyou route required the railroad to climb at least five grades between Eugene and the California border. But the main population centers, including Roseburg, Grants Pass, and Medford, were on the Siskiyou Route, so the rail line went there.

In 1905, Edward Harriman sought to rectify this problem by planning construction up the Middle Fork of the Willamette River over the Cascades. This route started from the east side line, which had terminated outside of Springfield. In 1891 Oregon pioneer geologist Thomas Condon had suggested to Southern Pacific that they name that spot Natron, after a mineral called Natrolite that was found in abundance nearby. Since this became the starting point for the Cascade line, it was sometimes called the Natron Cutoff.

Harriman’s death in 1909 was followed by years of litigation over control of the Southern Pacific as the federal government at that time believed a merger of the Union and Southern Pacific railroads would be monopolistic. This interrupted construction, which wasn’t renewed until 1924.

In the 1860s, the Central Oregon Military Wagon Road Company headed by Bynon Pengra and William Odell constructed a road from Eugene to eastern Oregon in order to get an 875,000 acre land grant. (The company eventually got only 235,500 acres.) The wagon road also went up the Middle Fork of the Willamette but crossed the Cascade divide south of Diamond Peak at a pass originally known as Willamette Pass, which was 5,600 feet high.

The railroad decided on a route north of Diamond Peak that was less than 5,200 feet high, mainly because of the lower elevation but also possibly because it was more scenic as it passed several large lakes just below the summit. This booklet called the summit Odell Pass after a lake just east of the summit that was named after William Odell. In 1927, however, the U.S. Board of Geographic Names named it Pengra Pass after Bynon Pengra.

In the 1940s, the state built a highway up the Middle Fork and said it crossed the Cascades at Pengra Pass. But the highway was actually a couple of miles northeast of Pengra Pass and about a hundred feet higher in elevation, 5,128 feet. In 1960, the highway route was redesignated Willamette Pass and the old Willamette Pass was renamed Emigrant Pass. Pengra Pass is not only 100 feet lower than Willamette Pass, the railroad went through a tunnel under the pass so its highest elevation was 4,843 feet.

This booklet points out that the Natron Cutoff shortened the Portland-San Francisco route by nearly 24 miles; that maximum grades on the new route were 2.2 percent vs. 3.3 percent on the Siskiyou Route; and that the new route required 2,870 feet less hill climbing than the old route. The new line also saved the equivalent of 51 complete circles of curvature, plus 10 more for a reroute in California.

The booklet added that the new route would allow passengers to view two completely different kinds of scenery by taking one route south and the other route north. The first named passenger train to use the new route that I can document was the Cascade, an extra-fare, all-Pullman train that didn’t begin operating until April 17, 1927. Another train, the West Coast, may have started that day or a few months before. This undated booklet does not mention that passenger service had yet begun, so it is probably from 1926.