Out of the 120,000 or so steam locomotives built and used in the United States, fewer than 220 were streamlined–or, as the Chicago & North Western called it, steamlined–for passenger service. Railroads went to the trouble to streamline steam locomotives for three reasons.

First, some railroads, such as the Burlington, wanted steam locomotives as a back up in case the Diesels that were powering most of their streamliners broke down.

Second, many railroads, such as the Milwaukee Road, didn’t believe Diesels were powerful enough to reliably pull a full-sized train, and travel demand in their markets required more than the little three- and four-car streamliners pioneered by Union Pacific and Burlington. The Santa Fe proved Diesels could pull a full-sized train in 1937, but some railroads stuck with tried-and-true steam technology for as much as a decade after that.

Third, some railroads decided it would far less expensive to put a shroud on an old steamer, making it look fast and new, than to buy new, expensive, and uncertain Diesels. Even the Union Pacific operated a supposedly streamlined (but actually mostly heavyweight) train with shrouded steam locomotives, counting the train among its fleet of streamliners.

Warning: This is a long post with more than two dozen pictures and may take some time to load. Clicking on most images will bring up a larger version–in some cases, particularly the posters, much larger. It is also unusual for this blog in that it doesn’t include any scans from my memorabilia collection.

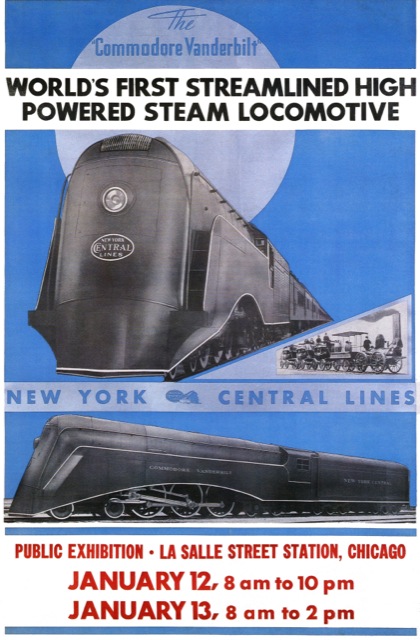

The New York Central was the first to fully streamline a steam locomotive in the United States, adding a shovel-nose shroud to a three-year old Hudson (4-6-4) locomotive and naming it the Commodore Vanderbilt. First made public in December, 1934, the locomotive entered revenue service pulling the railroad’s prestigious, but still heavyweight, 20th Century Limited in February, 1935. The New York Central later put a nearly identical shroud on a 4-8-2 steam locomotive to use hauling a rolling showroom for Rexall Drug Company.

The Central claimed its tests showed that streamlining enabled the locomotive to pull 2.5 to 12 percent more weight. The lower number is probably more accurate; streamlining was for advertising more than for faster or more efficient locomotives.

As designer Otto Kuhler noted in a 1935 speech, despite major technological improvements (such as superheating and roller bearings), “the man on the street” couldn’t distinguish a 1915 locomotive from a 1935 locomotive. Putting a shroud on one made it special–as some railroads would discover when they put shrouds on 1915 locomotives.

The next streamlined locomotives were the Hiawathas, which as I’ve already discussed, were introduced in April, 1935. Designed by Otto Kuhler, their significance is that they were the first American steam locomotives that were streamlined when they were built rather than shrouded later.

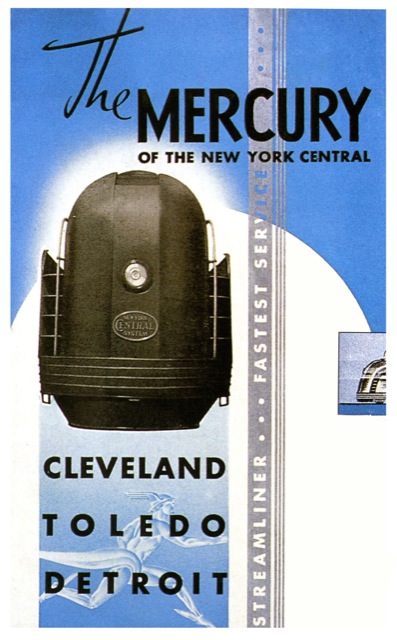

The New York Central asked Henry Dreyfuss–perhaps the nation’s second-most notable industrial designer–to design a train for Cleveland-Detroit service called the Mercury. Dreyfuss saved the railroad millions of dollars by suggesting that it rebuild 10-year-old commuter cars to his design, and to lead the train he put a shroud on two 4-6-2 Pacific locomotives. Introduced in May, 1936, their design became known as a “bathtub” style and was derided by many people.

In response to rival New York Central, the Pennsylvania Railroad asked Raymond Loewy–probably the world’s leading industrial designer–to design a shroud for one of its many Pacific locomotives. Loewy’s design, sometimes called a torpedo or bullet style, looked much more like a steam locomotive–but a very fast one–than the Zephyr that the Commodore Vanderbilt was clearly imitating. Loewy’s style would be favored for most future steamliners, even those designed by Dreyfuss.

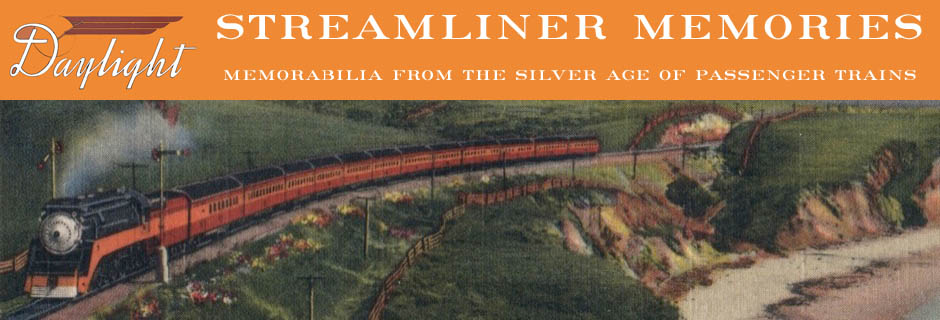

On the West Coast, the Southern Pacific was another railroad that didn’t seem to trust Diesels, so when it streamlined its San Francisco-Los Angeles trains, it ordered semi-streamlined Northern (4-8-4) locomotives from Lima (the “Chrysler of steam locomotive manufacturers”). The first entered service in March, 1937, and eventually SP would own 36 of these locomotives. Despite their lack of full streamlining, they were very popular due to their bright orange-and-red color scheme. As previously noted, the SP also semi-streamlined some older (1913) Pacifics for its Sunbeam train from Dallas to Houston.

Also in March, 1937, Baldwin Locomotive Works delivered the first of ten streamlined Hudson locomotives to the New Haven Railroad, which operated between Boston and New York. The engines pulled a train called the Shore Liner between Boston and New Haven.

In April, 1937, the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy unveiled the Æolus, which it billed as the first stainless-steel streamlined steam locomotive. Based on a three-year-old Hudson, locomotive #4000 was actually the first of two–the other numbered 4001–both named Æolus. (Click here to download a PDF of a Burlington brochure on the Æolus.)

Rail crews called the locomotives “Big Alice the Goon,” after a character out of Popeye. But they were fast, easily reaching 100 mph and, rumor has it, sometimes hitting 120 mph. Of course, they were designed to resemble the Zephyr locomotives, even down to the grills, and the profile of the tenders perfectly matched that of the Twin or Denver Zephyr’s lead car.

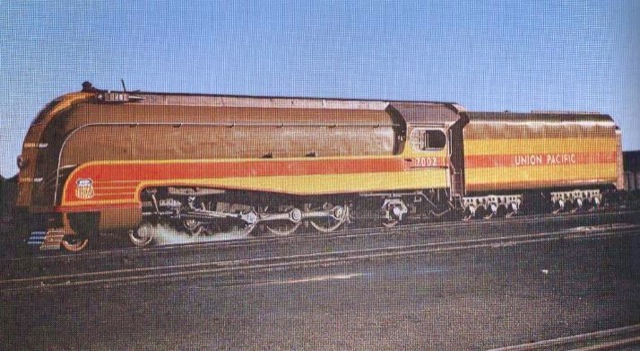

In 1937, the Union Pacific inaugurated the 49er, a five-times-a-month all-Pullman train from Chicago to Oakland to complement its five-times-a-month City of San Francisco on the same route. Except for the observation car, all the cars on the Pullman train were heavyweights. To give it a streamlined aura, it shrouded two locomotives: a 4-6-2 and a 4-8-2.

The locomotives were painted brown with bright yellow and red trim to match the railroad’s Diesel-powered streamliners (but not the heavyweights that the locomotives actually pulled). The 4-6-2 was used on the plains between Omaha and Cheyenne while the 4-8-2 was used in the mountains from Cheyenne to Ogden.

Otto Kuhler designed the 1937 Royal Blue, which was the Baltimore & Ohio’s attempt to compete with the Pennsylvania in the New York-Washington corridor. His bullet-style streamlining was applied to a ten-year-old Pacific locomotive that had been built by Baldwin. The streamlining didn’t last long, as the B&O replaced the locomotive with General Motors E units in 1939. After going unstreamlined for eight years, the locomotive was later re-streamlined for the Cincinnatian.

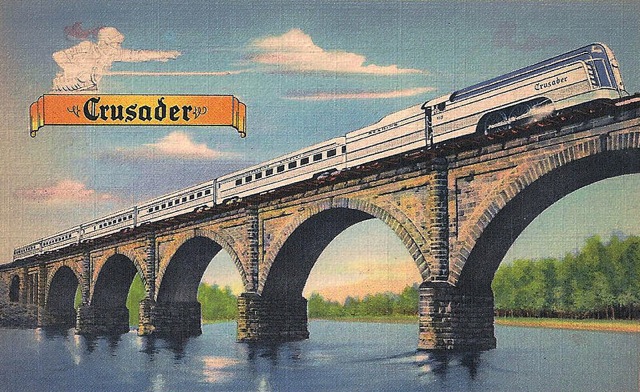

In December, 1937, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad introduced the Crusader, a Budd-built train that, starting the following February, made twice daily round trips between Philadelphia and Jersey City, a short ferry ride from lower Manhattan. To avoid having to turn the train at each terminus, the stainless steel train had observation cars at both ends.

The matching stainless steel steam locomotive, originally built in 1918, was also distinguished by having a tender that wrapped around the observation car, which no doubt obstructed views but perhaps added slightly to the tender’s capacity. The shroud increased the weight of the locomotive by 12 percent (nearly 33,000 pounds), which was not necessarily a bad thing for steam locomotives as more weight means more traction, allowing faster starts with less slippage.

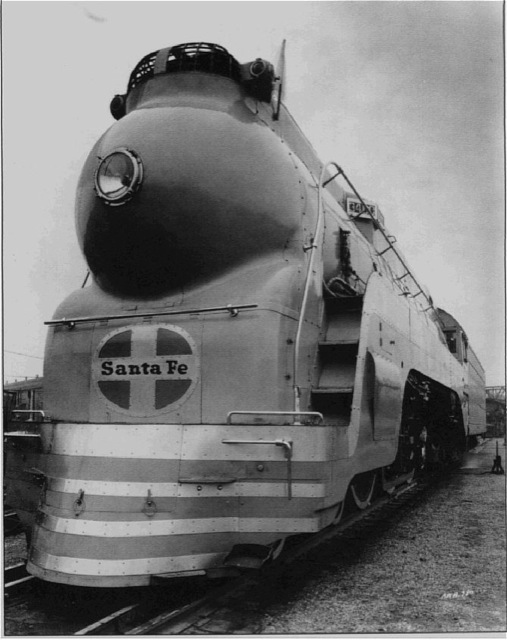

In January, 1938, Baldwin delivered a streamlined Hudson to the Santa Fe. The locomotive weighed about 8,000 pounds and cost about $15,000 more than non-streamlined Hudsons in the same order. Although the Santa Fe planned to use the locomotive with its passenger trains, it made no attempt to replicate the Warbonnet color scheme, instead painting the locomotive light blue. The Santa Fe used the locomotive and its unstreamlined sister Hudsons to pull passenger trains from Chicago to La Junta, Colorado, a run of nearly 1,000 miles.

In September, 1939, Alco–the same company that made the Milwaukee’s Hiawatha locomotives–delivered new Kuhler-designed streamlined locomotives to the Chicago & North Western that the railroad bragged were the largest and most powerful Hudsons ever. Painted dark green with yellow stripes, the locomotives were intended for use on the 400 in competition with the Hiawathas. Ironically they turned out to be more powerful than needed for the day trains that ran between Chicago and the Twin Cities, so the C&NW used them for the Chicago-Omaha trains that connected with the Union Pacific to the West Coast.

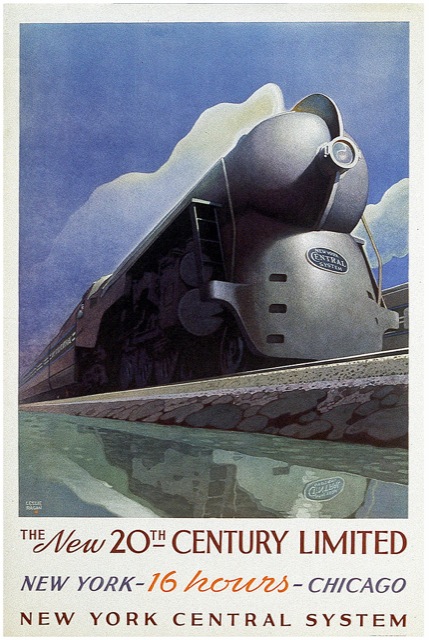

In March, 1938, the New York Central received the first of ten Hudson locomotives built by Alco and streamlined following a design by Henry Dreyfuss. These are arguably the most famous streamlined steam locomotives ever, partly because the New York Central’s publicity department was relentless in promoting them. The railroad would use them to pull its new streamlined 20th Century Limited, which was also designed with Dreyfuss’ help.

Though Dreyfuss had adopted the bullet style instead of the bathtub style he used for the Mercurys, some argued that Loewy’s designs, which emphasized the horizontal, were more appropriate for trains than the Dreyfuss 20th Century Limited locomotives, which from the front at least emphasized the vertical. The Central would later restreamline the Commodore Vanderbilt in a similar style.

With an eye on competitor C&NW, the Milwaukee Road took delivery of new Kuhler-streamlined Hudson locomotives from Alco in late 1938. Milwaukee’s Hudson’s were slightly smaller and less powerful than the C&NW’s, but they were sufficient to haul fifteen or more cars between Chicago and the Twin Cities at the Hiawatha’s usual top speeds of more than 100 mph. In fact, they reputedly reached an unofficial top speed of 125 mph, which would make them equal to the fastest officially recorded steam locomotives in the world.

Like the New York Central, the Lehigh Valley Railroad’s main line was between New York City and Buffalo. They weren’t really competitors as the Lehigh’s circuitous route meant trains would take hours longer than on the Central’s “water-level route.” But the Lehigh accessed anthracite coal fields, leading it to call its premiere train the Black Diamond. In 1939, the railroad asked Otto Kuhler to streamline several of its older Pacific locomotives. They were painted bright red and black–the colors of Cornell University–and paired with similarly painted heavyweight, but remodeled, passenger cars.

In response to Dreyfuss’ 20th Century Limited, the Pennsylvania asked Loewy to design a new Broadway Limited, and as a part of that commission he also helped design the S1, a remarkably innovative “duplex” locomotive, meaning one with two pairs of cylinders, each driving four wheels, whose drivers do not independently rotate with the curvature of the track. The engine had six-wheel leading and trailing trucks, making it the only 6-4-4-6 ever built.

The goal was to build a locomotive as fast and powerful as the GG-1 electric engines that Loewy also helped design. The supposed advantage of two sets of cylinders was that the reciprocating parts that drove the wheels could be lighter in weight and thus cause less damage to track at high speeds. While the S1 was fast and beautiful, its long rigid wheelbase meant it could only work on tracks that had very gentle curves. No more were ever built and the locomotive was scrapped after only ten years.

In December, 1939, the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad (which never came close to San Francisco) began operating a heavyweight, but semi-streamlined, train between Kansas City and Oklahoma City called the Firefly. The train was pulled by three crudely streamlined Pacific locomotives that dated back to 1910. Locomotive and train were painted blue and aluminum.

Having learned from the S1s, the Pennsylvania ordered 4-4-4-4 locomotives, designated T1s, from Baldwin. The first were delivered in spring, 1942, enshrouded by Raymond Loewy in what became known as the “shark-nose” style. Not as pretty as the S1, the T1s operated well enough that the Pennsy eventually bought 50 from Baldwin.

In 1941, Otto Kuhler streamlined a 1923 Alco Pacific locomotive for the Southern Railway for use on its Tennessean train, which (in conjunction with the Pennsylvania and Norfolk & Western) connected New York with Memphis. One of the Southern Railway’s bright green Pacific locomotives is displayed in the Smithsonian Museum, and the Tennessean locomotive combines this color scheme with the bullet-style of the B&O Royal Blue.

In October, 1941, the Norfolk & Western–which built many of its own locomotives–completed the first of fourteen streamlined Northern (4-8-4) steam engines. Large drivers mean faster speeds, but rather than the 80-inch drivers on the Southern Pacific’s Daylights, the N&W elected to put 70-inch drivers on its Northerns and compensate by carefully balancing the drive gear (to minimize track damage at high speeds) and increasing boiler pressures to 300 psi. The resulting locomotives were the most powerful Northerns ever built and nearly twice as powerful as many of the Hudsons streamlined by other railroads.

Later, the railroad also shopped 22 of its Mountain (4-8-2) locomotives with similar styling. A coal railroad, the Norfolk & Western resisted the Diesel revolution for longer than any other major U.S. railroad, and operated these steam locomotives as late as 1958.

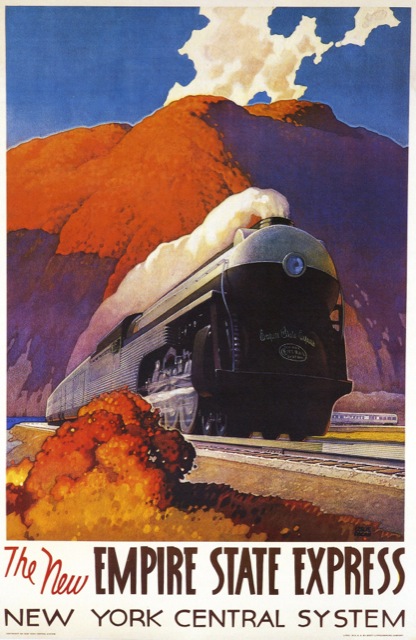

In December, 1941, the New York Central introduced a new, Budd-built train between New York and Cleveland called the Empire State Express. Leading these trains were Dreyfuss-designed Hudsons that many would argue were an aesthetic improvement over the 20th Century Limited locomotives. Partly clad in stainless steel, the boiler and smokebox were painted in aluminum and black, emphasizing the horizontal rather than the vertical.

The four locomotives for the Baltimore & Ohio’s Cincinnatian, one of which had previously been streamlined by Otto Kuhler for the Royal Blue, were notable for having been designed by Olive Dennis, the first woman civil engineer ever employed by a U.S. railroad. Dennis’ design clearly owes a debt to Kuhler.

The two five-car trains themselves consisted of heavyweight cars modified by B&O shops to appear streamlined. The train operated between Baltimore and Cincinnati from 1947 through 1950, then was changed to a Cincinnati-Detroit run which it maintained until 1956, when Dennis’ steam locomotives were replaced by General Motors Diesels.

In 1946, the mercurial Robert Young–CEO of the Chesapeake and Ohio who was married to Georgia O’Keefe’s sister and who famously criticized American railroads by saying, “A pig can go from coast to coast without changing trains, but you can’t”–ordered a dome-car train from Budd that he planned to run between Washington DC and Cincinnati. To power the train, the C&O–like Norfolk & Western, a coal railroad–rebuilt four two-decade-old Pacific locomotives into Hudson’s with stainless steel sides and a unique, orange-painted, forward-thrusting nose.

Unfortunately, the train, which was to be called the Chessie, never ran, as the railroad decided (based partly on the experience of the B&O’s streamlined Cincinnatian) that there was little market for passengers in that corridor. By 1948 it had sold most of the Budd cars to other railroads. The C&O’s experiments with a steam-turbine locomotive also failed, and the railroad quickly converted to Diesel’s despite its access to cheap coal.

Probably the last “steamlined” train in the U.S. was the City of Memphis, which the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis began operating between Nashville and Memphis in May, 1947. Given a limited budget, the railroad put a shovel-nose shroud on one of its Pacific locomotives and rebuilt heavyweight passenger cars, giving them a streamlined appearance.

I may have missed a couple, but based on Kevin Holland’s book, Steam Liners, I count 213 streamlined steam locomotives in the U.S., from the Commodore Vanderbilt to the City of Memphis (not all of which are represented here) At least 50 Northerns were streamlined, all by the Southern Pacific and Norfolk & Western. That number is tied by the Pennsy’s 50 peculiar 4-4-4-4 T1s. The next most were Hudsons, of which I count 43 (one of which, the Commodore Vanderbilt, was streamlined twice), owned by six different railroads.

Well over a dozen railroads streamlined at least 41 Pacifics (one of which was streamlined twice). While the Northerns, T1s, and many Hudsons were new, virtually all of the Pacifics were modifications of existing locomotives, mostly 10 to 25 years old. Other than Pennsy’s 6-4-4-6, the only other wheel class to be streamlined was the 4-8-2: the N&W did 22 Mountains, while the Union Pacific and New York Central each did one, all modifications of existing locos.

As previously noted, streamlining was for publicity purposes only. It didn’t particularly save energy, partly because it added thousands of pounds to the weight of the locomotive. It didn’t make the locomotives go faster, though other modifications such as roller bearings, lighter-weight driving rods, and improved balancing did.

Many railroads that introduced steamlined trains claimed higher ridership on the trains, much of which was due to faster speeds and more comfortable cars, but some likely due to the publicity earned by the improved appearances. In the end, streamlined steam played a small but significant part of the transition from heavyweight to lightweight passenger trains and from steam to Diesel power.