Three days ago, I posted the system timetable for November 1964. We’ve previously seen timetables for May 1965, November 1965, May 1966, November 1966, and June 1967. That brings us to today’s timetable.

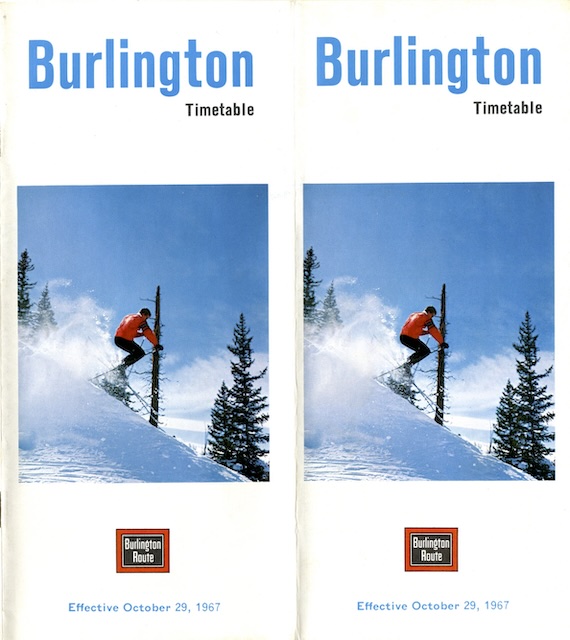

Click image to download an 10.7-MB PDF of this 20-page timetable.

Click image to download an 10.7-MB PDF of this 20-page timetable.

The intervening three years brought some major changes. Most apparently, after more than 80 years of publishing timetables with a deep red background with a prominent Burlington Route white-on-black logo, the railroad abruptly changed, in May 1966, to timetables with a white background, a large, cheery color photo, and a miniscule Burlington Route logo.

Ironically, this dramatic change may have been due to the retirement of pro-passenger train President Harry Murphy and his replacement with passenger-train skeptic Louis Menk in October 1965. In his previous job as president of the Frisco, Menk had worked to terminate all of that railroad’s passenger trains, giving him the reputation of being anti-passenger.

As Fred Frailey notes in his book, Twilight of the Great Trains, Menk wasn’t really against passenger trains; he was against money-losing trains. If a passenger train made money, he was for it. When Western Pacific wanted to terminate the California Zephyr, on which it was losing money, Menk opposed it. After all, the Burlington was still making money on it.

(Passenger train economics is a funny thing. Burlington figures may have shown that the California Zephyr lost money when costs were allocated to all of the trains on that route. But if the CZ eliminated, Burlington would still have to pay for ticket agents, station upkeep, baggage handling, and other costs on the Chicago-Denver route so long as it ran the Denver Zephyr and other passenger trains on that route. Frailey notes that three Burlington trains a day in the Twin Cities corridor lost $700,000 a year, but cutting one of those trains would save only $13,000 a year, and annual ticket sales on that train were undoubtedly more than $13,000. Similar numbers were probably true for the Denver corridor. The Western Pacific didn’t have other passenger trains so would save a lot more by cutting the Zephyr.)

Effectively, Menk challenged Burlington’s passenger department to cut costs and get more revenues. I don’t know for sure, but the timing suggests that these redesigned timetables were one of the results: Menk took over in October, questioned Burlington’s passenger program, and in May the railroad issued timetables with fresh new covers aimed at attracting the eyes of potential new customers.

Menk was Burlington’s president for only a year. By the end of that year, however, it was clear to even the most pro-passenger executives that the days of passenger trains were numbered, so trains started to disappear at an accelerated rate.

The Sam Houston Zephyr was dropped as of the May 1966 timetable. A train between Casper and Guernsey, Wyoming disappeared from the November 1966 timetable. The June 1967 timetable dropped the Texas Zephyr (ending Burlington passenger train service in Texas) and Zephyr-Rocket. Today’s timetable dropped the trains from Denver to Billings and Denver to Alliance (which is on the Kansas City-Billings route). In addition, the ambiguously mixed trains (“consult your agent for details”) and freight-service only schedules are gone, allowing Burlington to reduce this timetable to just 20 pages. (Note that these were all routes that had only one train per day before being dropped.)

To save a little more money, in November 1966 the Empire Builder and North Coast Limited were combined into one train in both eastbound and westbound directions between Chicago and the Twin Cities. This was made possible by both railroads changing the schedules of their premiere trains so that the North Coast Limited left Chicago about an hour later than before while the Empire Builder left about an hour earlier.

This timetable takes another step in combining both the Empire Builder and North Coast Limited were combined with the Afternoon Zephyr westbound and Morning Zephyr eastbound. Since the Western Star and Mainstreeter were both combined with other trains in both directions, the westbound Morning Zephyr was the only train to run by itself. This reduced the Burlington to just three daily round trips in this corridor.

When the Empire Builder had been combined with the North Coast Limited, the former train lost its observation car. Now that the two were combined with one of the Twin Zephyrs, the North Coast Limited had to yield up its observation car. To provide beverage service to first-class passengers, Northern Pacific replaced a sleeping room beneath one of the dome sleepers on each train with a small buffet so passengers in the dome had easy access to drinks.

This had a much bigger impact on passengers than the elimination of the Empire Builder‘s observation car, which had only eight seats and no food or beverage service. The “lounge in the sky,” as NP called its dome lounge, had fewer seats than the observation lounge it replaced.

Moreover, NP had rearranged the dome by adding six tables and turning the seats so that half the passengers faced backwards. This effectively reduced the number of dome seats available to pure sightseers (especially those who liked to look ahead) as opposed to people who wanted a drink. This downgrade in service was necessary only to allow the Burlington to save a few dollars by combining three trains into one in the St. Paul-Chicago corridor.