In the turn-of-the-20th-century corridors we’ve examined to date — New York-Chicago, Chicago-Los Angeles, Chicago-Seattle, and Chicago-Twin Cities — a large share of the passengers were traveling for business. In the Florida corridor, however, most travel was for pleasure.

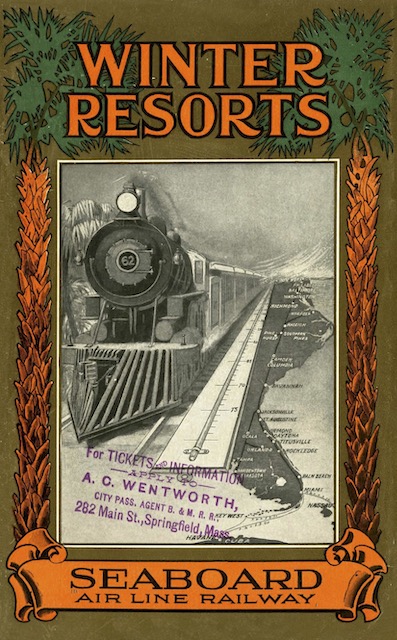

This 1906 booklet, which is from archive.org, describes the high-class resorts people could enjoy in Florida. Much of the booklet consists of fold-out pages which archive.org had incorrectly laid out in the PDF it has posted on line. I am pretty sure I fixed that problem. Click image to download a 13.9-MB PDF of this 36-page booklet.

This 1906 booklet, which is from archive.org, describes the high-class resorts people could enjoy in Florida. Much of the booklet consists of fold-out pages which archive.org had incorrectly laid out in the PDF it has posted on line. I am pretty sure I fixed that problem. Click image to download a 13.9-MB PDF of this 36-page booklet.

Another difference between this and most of the other corridors I’ve examined is that the railroads serving Florida were mostly amalgamations of other smaller rail lines. While there were a few powerful railroad owners who influenced the region, there were no heroic construction sagas like the First Transcontinental Railroad or the First Transcontinental Railroad to be built without government subsidies (i.e., the Great Northern).

From 1900 to 1915, three great railroad systems competed in this corridor. The Atlantic Coast Line began offering service to Florida in the late 1870s with service that took more than 73 hours to get from New York to Jacksonville. The Piedmont Air Line entered the market in 1894 just a few months before it merged with other roads to become the Southern Railway. The Seaboard Air Line and its predecessors started out with New York-New Orleans service but began serving Florida in 1900.

Curiously, a major obstacle to Florida service was not the terrain but the government. While states and cities across the country were falling over themselves to attract new railroads, steamship companies had persuaded the Florida legislature to pass a law forbidding the construction of a railroad across the state line.

During the Civil War, the Confederate government itself built a rail line from Lawton, Georgia to Live Oak, Florida, and this became the main way of getting into the state by rail. But it was an inconvenient route. Most trains from New York went through Savannah, and Savannah to Jacksonville via Live Oak took almost 16 hours for a trip that takes two hours by automobile today.

In 1881, a Connecticut-born entrepreneur, Henry Plant, owned several railroads in Georgia and Florida, including the line between Lawton and Live Oak. But he knew this was an indirect route so he conceived of a way around the law against building across the Florida state line.

First, he built the Waycross and Florida from Waycross, Georgia (which was connected with Savannah) to the St. Marys River, which was the boundary between Georgia and Florida. From Jacksonville, he had a railroad called the East Florida build north to the St. Marys River. Where each railroad met the river, he built a dock out into the river. By an amazing coincidence, the docks met in the center of the river, so he built tracks on the docks.

This certainly violated the spirit if not the letter of the law, but he got away with it (perhaps because someone at the state level realized that the law violated the interstate commerce clause of the U.S. Constitution). He called this the Waycross Short Line and it shaved 10 hours off the trip between Savannah and Jacksonville.

Jacksonville itself wasn’t a tourist destination, but due to the Waycross Short Line it became the rail gateway to Florida. Whether you came from Chicago, Cincinnati, or New York, whether you rode the Atlantic Coast Line, Southern, or Seaboard, and whether your destination was Tampa or St. Petersburg on the West Coast or St. Augustine or West Palm Beach on the East Coast, you had to come through Jacksonville.

In 1881, before the Waycross Short Line opened, the Atlantic Coast Line’s fastest train took around 59 hours to get from New York to Jacksonville. In 1882, thanks to the short line, this was cut to 45 hours.

Built in 1894, this is one of ACL’s order of the first Atlantic-type locomotives built with a wider firebox supported by a two-wheel trailing truck. The locomotive produced about 18,400 pounds of tractive effort and its 72″ drivers could haul trains to Florida faster than the locos it replaced. Click image for a larger view.

This spurred construction of several rail lines the length of the Florida peninsula. Plant himself built a rail line to Tampa and a large resort there, essentially putting that community on the map. A Rockefeller partner named Henry Flagler first visited Florida in 1879 due to his wife’s ill health and ended up building hotels in St. Augustine, West Palm Beach, Miami, and Key West, all connected by his Florida East Coast Railway.

All three New York-Florida railroads offered two or more daily trains between New York and Florida. The Atlantic Coast Line and Seaboard actually began in Richmond and relied on Pennsylvania Railroad (or, in the early days, steamships) to get to Washington and Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac to get the Richmond. Southern had its own tracks south of Washington but also relied on PRR between New York and Washington.

The three railroads’ premiere, all-Pullman trains generally operated only in the winters. Initially, the railroads didn’t have special names for those trains, usually calling the premiere trains on each route the “vestibuled train.” According to Wikipedia, ACL inaugurated a winter-only, all-Pullman train called the New York and Florida Special on January 9, 1888, but the Official Guide continued to call it the “vestibuled train” until 1889.

When the Piedmont Air Line began New York-Florida service in 1894, it called itself the “Florida Short Line” but didn’t have a particular name for the train other than “vestibule limited.” This continued after Piedmont was consolidated with several other railroads into the Southern.

These two nearly identical ads are from the June and September issues of the Official Guide, in other words, just before and just after Piedmont merged with Richmond & Danville and other railroads to form the Southern. Note that the “R&D” and “SR” logos are similar to one another. Click each image for larger views.

“Magnificent and elegantly appointed trains, carrying Pullman Drawing-room Sleeping Car New York to Jacksonville and Tampa without change. Dining cars between Danville and Charlotte,” said the Southern ad in the September 1894 Official Guide. “No Extra Fare on the Vestibule Limited. Carrying only Pullman Sleeping and Dining Cars.” By this time, trains on both the ACL and Southern took only 30 hours to get from New York to Jacksonville.

In 1895, Southern designated its train with the unwieldy name of New York and Florida Short Line Limited. ACL, meanwhile, had shortened the name of its train to simply Florida Special, a name that would survive until Amtrak. They also continued to shorten their train times, with both Southern and ACL reducing New York-Jacksonville times to about 25 hours by 1900.

In 1900, Seaboard Air Line took over the Florida Central and Peninsular Railroad, which had in-state lines from Jacksonville to Tampa and Orlando, giving the Seaboard access to Florida for the first time. It began New York-Florida service almost immediately and, on January 14, 1901, started an all-Pullman New York-Jacksonville train it called the Florida and Metropolitan Limited. In 1903, it renamed the train Seaboard Florida Limited during the winter and Seaboard Florida Express in the summer.

Meanwhile, ACL took over the Plant system in 1902. Seaboard built its own short-cut from Savannah to Jacksonville that was even shorter than the Waycross Short Line. This set the stage for an intense competition that would continue until the two railroads merged in 1967.